The Competition for Bukan:

The Rivalry between Suwaraya and Izumoji

By Han Qiaoyu

Abstract:

Suwaraya Mohē 須原屋茂兵衛 was one of the leading publishers in Edo in late eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth centuries. Its founding could be traced by to the Manji era (1658–1661) when the founder Kitabatake Sōgen 北畠宗元 (n.d.) established Suwaraya Mohē as a bookshop in Tōri-itchōme通一丁目in Nihonbashi 日本橋, Edo. In 1817, twelve publishers of the sixty-three members of the Edo bookshop association (Edo shomotsuya nakama 江戸書物屋仲間) bore the Suwaraya name and these firms were associated with one third of all the books published or distributed in Edo. Suwaraya Mohē was well-known for its publishing of Guide to Military Houses (bukan 武鑑). This essay looks into the rivalry between Suwaraya Mohē and the publisher Izumoji Izumi 出雲寺和泉 on the various matters concerning the publication of bukan in the Tokugawa period. It argues the struggle between Suwaraya Mohē and Izumoji Izumi reflected the struggle between Edo publishers and Kyoto/Osaka publishers’ branch shops in Edo, while the final monopoly of bukan publication by Suwaraya Mohē is a result of their business strategy of accumulating publishing capital on bukan.

Keywords: Edo, publisher, Suwaraya Mohee, Izumoji Izumi, bukan

Introduction

The development of publishing industry in the Tokugawa period (1603–1867) enabled a variety of innovations in terms of the content of printed books. Bukan 武鑑 was one of such newly invented categories of publications which served as the guide to military houses. The publishing of bukan emerged in the mid-seventeenth century and was gradually being monopolized by two main publishers: the local publisher Suwaraya Mohē 須原屋茂兵衛 and the Kyoto founded Izumoji Izumi出雲寺和泉.

The publishing of bukan required a large amount of work into gathering the relevant information. Although bukan was presented to the shogunate every year, it was still a private publication.[1] Therefore, the publishers needed to find ways to gather as much information as possible directly or indirectly about, first of all, the domain lords, and secondly, the important hatamoto 旗本 (bannerman) who occupy high offices in the shogunate. Further, the publishers need to make the content of their bukan as accurate as possible. This means that the information they gathered might be wrong and it has to be updated constantly according to personnel changes in the shogunate.

This essay investigates the development of bukan and the actual process of making it. The focus of this essay is on the rivalry of the two main publishers of bukan in the second half of the Tokugawa period. It argues that the struggle between Suwaraya Mohē and Izumoji Izumi reflected the struggle between Edo publishers and Kyoto/Osaka publishers’ branch shops in Edo, while the final monopoly of bukan publication by Suwaraya Mohē is a result of their business strategy of accumulating publishing capital on bukan.

The essay is divided into the following sections: first, I introduce the evolution of bukan and how it ended up in the final format in mid 1700s; second, I describe the process of making a bukan and how it was distinguished from other categories of publications during the Edo period; third, I discuss the legal conflicts between Suwaraya Mohē and Izumoji Izumi in their claim of certain copyrights upon the publishing of bukan; fourth, I examine the key strategies for the success of Suwaraya.

The Development of Bukan

The earliest known book that could be categorized as bukan is Godaimyō-shū gochigyō jūman koku made 御大名衆御知行十万石迄 published in Kan’ei 寛永 20 (1643) by Hon’ya Jinzaemon本屋甚左衛門 in Kyoto.[2] The emerging of bukan is closely linked to the policy of alternate attendance system that was introduced in Kanei 12 (1635) by the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu 徳川家光 (1604–1651). The alternate attendance system requires all daimyo to live between Edo and their home domains every other year. The gathering of daimyo in Edo created the opportunity for close observation of the progressions of every domain to record their family crests, the looks of their palanquins, the spears that the guards held and so on. The system also created the need for a book that could be used to quickly search for information about the officials and the personnel changes in the daimyo domain and the shogunate.

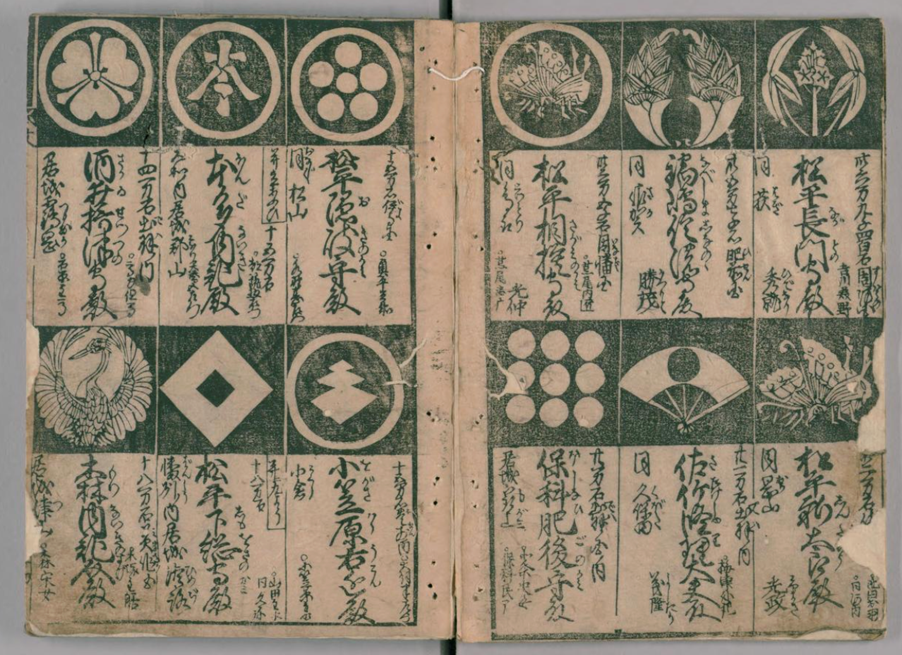

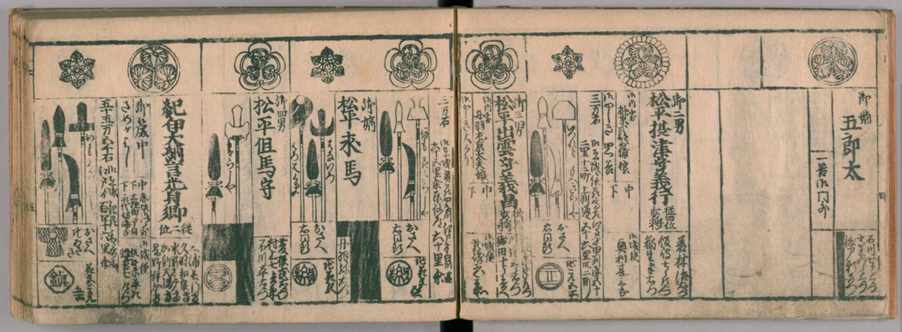

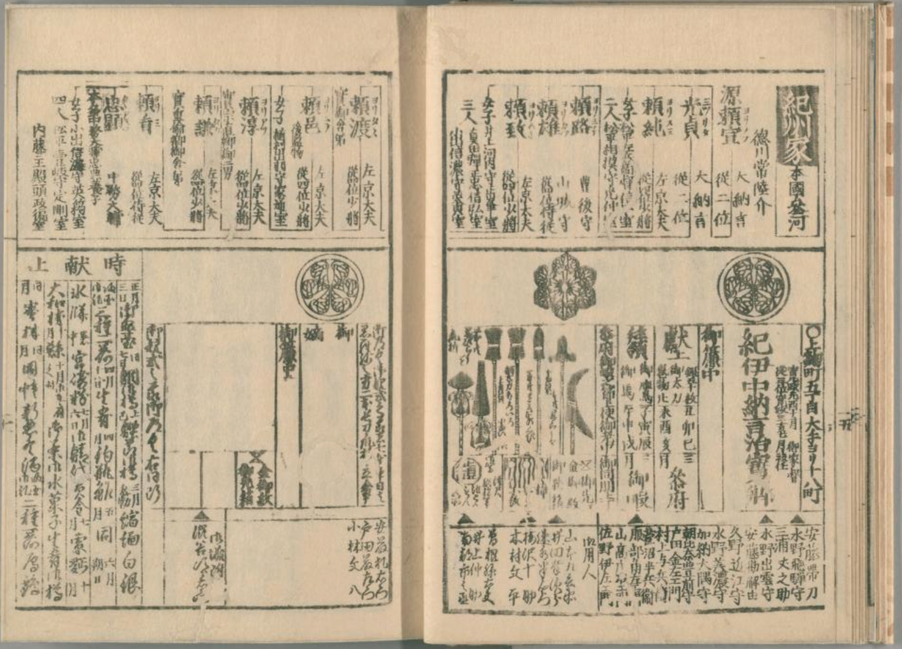

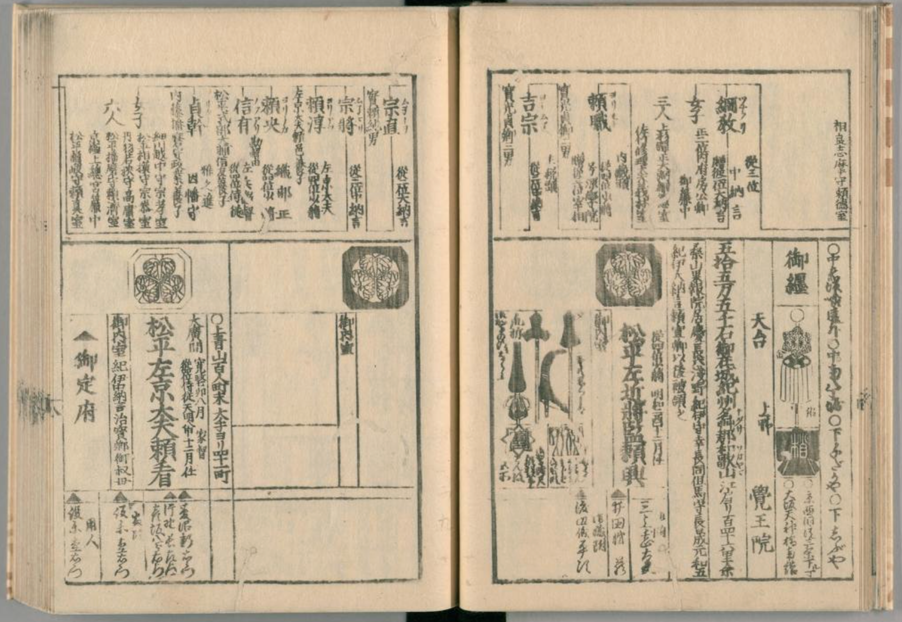

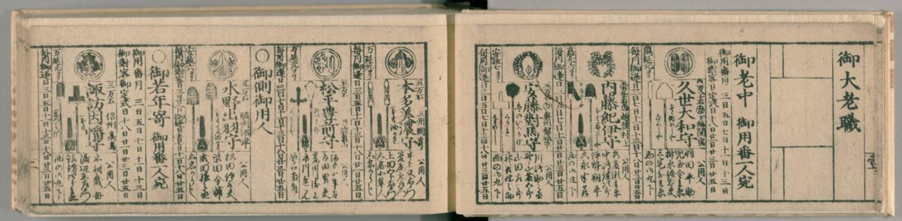

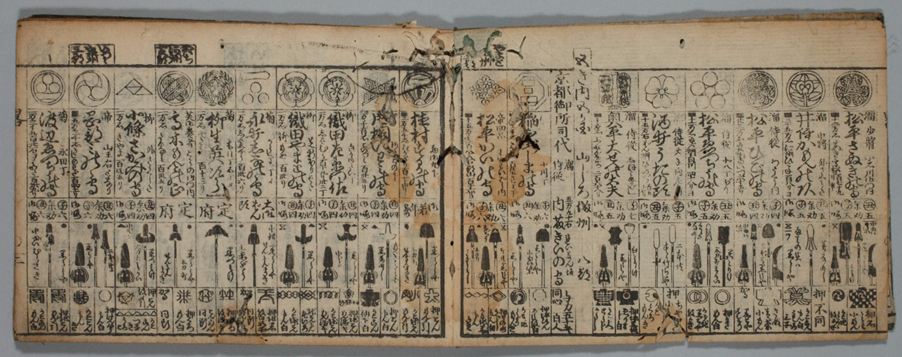

The content of bukan and the layout of the pages have experienced a constant evolution during the Edo period. Nevertheless, most of the important changes occurred in the first half of the Edo period while in the second half there only occurred minor changes to a somewhat fixed template. Figure 1 shows the Gomonzukushi 御紋尽 published in Meireki 明暦 2 (1656) by Nishizawa Tahē 西沢太兵衛 in Edo. There is not much information about the daimyo family in it. Comparing it to Figure 2, which shows Taihei bukan 太平武鑑 published in Genroku 元禄 8 (1695) by Sunhara Mohē 寸原茂兵衛 in Edo, we can observe that, first of all, the format of the book and the layout is very different from Gomonzukushi, and second, there is an addition information about the shape of the spears that the retainers carry in the procession in each daimyo family. Moving on to the Kansei bukan 寛政武鑑 published in Kansei 寛政 8 (1796) by Suwaraya Mohē (see Figures 3 and 4), again, the format and the layout has dramatically changed. While Gomonzukushi describes six families in one page, the Kansei edition could not provide all the information about one daimyo in two full pages. In fact, the description of the Tokugawa family of the Kii domain occupied nearly four pages.

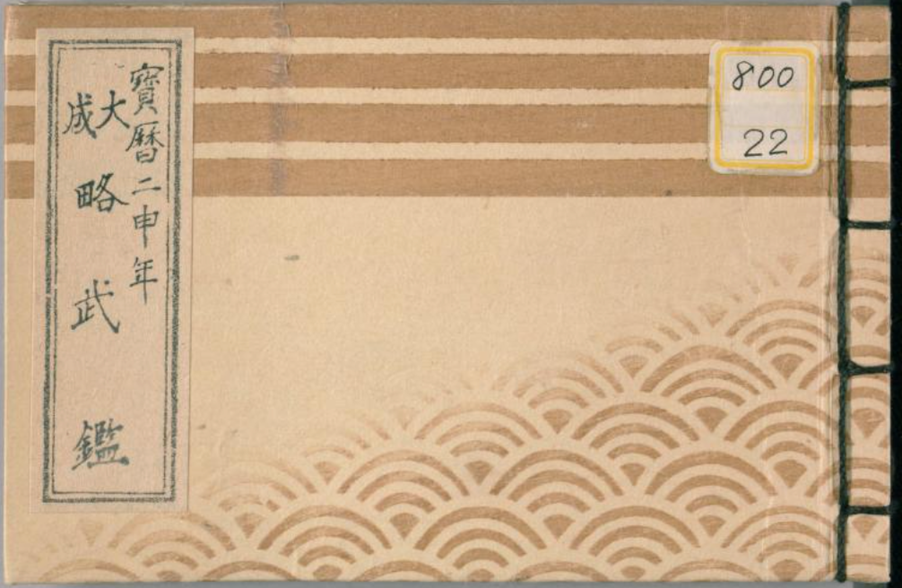

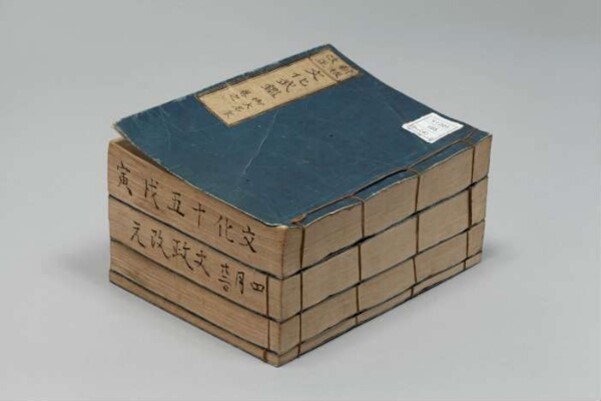

Starting from the eighteenth century, a new kind of embukan/em that is smaller in size and briefer in content, called emryaku bukan/em 略武鑑 (Brief Guide to Military Houses) was produced. Depending on the amount of briefing, emryaku bukan/em also varies from one to another. Here I want to introduce the different formats of embukan/em that Suwaraya Mohē produced after 1700 as an example. First there is the most comprehensive embukan /emthat is titled according to the era name of the time of publishing such as emKansei bukan/em 寛政武鑑. This kind of embukan/em is often generally called as emdaibukan/em 大武鑑 (Great Guide to Military Houses).[3] The size of this kind of bukan is roughly 15 ☓ 11 to 16 ☓ 12 cm. It consists of four volumes: volume one records the information about daimyo families that receive a stipend more than 100,000 koku[4] 石 of rice; the second volume records the information about daimyo families that receive a stipend between 100,000 and 10,000 koku; volume three records the information about the high officials in the shogunate such as the senior councilors the junior councilors and city magistrates; volume four records the information about the officials who protect the Nishinomaru 西丸,[5] where the heir to the current shogun and the retired shogun live. The information of this kind of bukan was constantly being added so the number of pages of daibukan was constantly increasing. In the nineteenth century, a daibukan would consist of five to six hundred pages with a thickness of more than ten centimeters (see Figure 5).[6] Since the sheer volume of daibukan is so enormous, it was not updated as frequently as the ryaku bukan. Suwaraya revises this kind of bukan every two to eight years.[7]

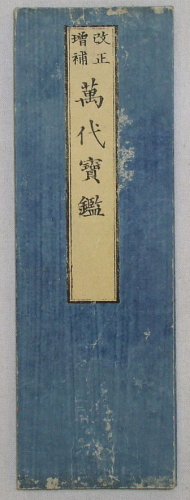

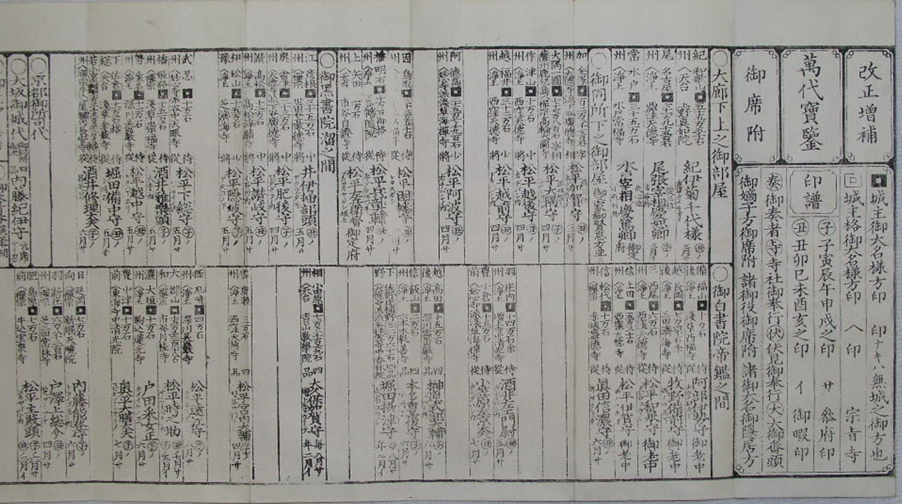

In terms of the ryaku bukan, Suwaraya provides several formats for their customers to choose from. Ryaku bukan only comes with one volume in every formats. Starting from Shūchin bukan 袖珍武鑑 (Guide to Military Houses to Carry in Sleeves; see Figure 6) and Shūgyoku bukan 袖玉武鑑 (Guide to Military Houses in Sleeves; see Figure 7), both meaning Pocket Guide to Military Houses and share the same size about 8 ☓ 18 cm. These bukan of a slim outfit are designed to be carried in the sleeves for daily use. The content of these bukan is designed for different need of the customers. The content of Shūchin bukan only focuses on the information about daimyo while the content of Shūgyoku bukan only focuses on the information about shogunal officials. Another format is the Kaihō ryaku bukan懐宝略武鑑 (Chest Guide to Military Houses; see Figure 8) which measures roughly 11 ☓ 16 cm. This kind of bukan provides information about daimyo families and shogunal officials in less detailed fashion while compresses the content of a daibukan into just over forty pages. Apart from bound bukan, Suwaraya also produces orihon 折本 (folded book) that is even more compact in size. For example, the Mandai hōkan 万代宝鑑 (see Figures 9 and 10) printed in Kaei 嘉永 3 (1850) measures roughly 6 ☓ 18 cm. The information in it is even more compressed without image. Ryaku bukan is usually revised yearly because the output of it is much higher than daibukan and the woodblock of ryaku bukan wears quicker than that of the daibukan.[8]

By producing different formats of bukan, Suwaraya managed to meet the various needs on the market. For example, for those who has an interest in the personnel changes in daimyo houses and the shogunate, comparing the records in daibukan from previous eras could be one of the most efficient way to conduct such research in the Tokugawa period. For those who has an interest in such matters, continuously purchasing and collecting daibukan is the best way to help them fulfil their needs. In fact, even after the Tokugawa period, daibukan was still being used as a source of information about the history of the period. One notable figure who is well-known for collecting and researching bukan is novelist Mori Ōgai 森鷗外 (1862–1922). Mori has consulted extensively from daibukan for his historical novels.[9]

For those who primarily uses bukan for daily work, the smaller ryaku bukan could be handy. One job that needed daily use of bukan was the kezami 下座見 (guard at the gates to the Edo Castle). These guards need to discern more than two hundred and sixty different daimyo houses that would enter the shogun’s castle on certain days of the year and keep the processions from falling into chaos. A handy bukan could provide crucial information about symbols of different daimyo houses for such guards for reference.[10]

The Making of Bukan

Making a book was not an easy task in Edo period. It requires the cooperation of a variety of specialists in different fields. The typical process of commercial printing in Edo period starts from copying the manuscript to producing a clean and readable copy, then the copy would be passed to a block-carver to make woodblocks. After the woodblocks are carved, it would be passed to a printer who did the actual printing. Apart from all these, there are specialists in making ink and paper. After printing, there are also professional workers to lineup the printed paper and those who bind the pages into books.[11] Fujizane Kumiko has examined the cost and profit of making and selling bukan. Her estimation is that, apart from the cost of collecting information and making woodblocks, profit consists roughly 10 to 15 percent of the price of different bukan depending on the physical sizes while the cost of paper consists about half of the cost.[12]

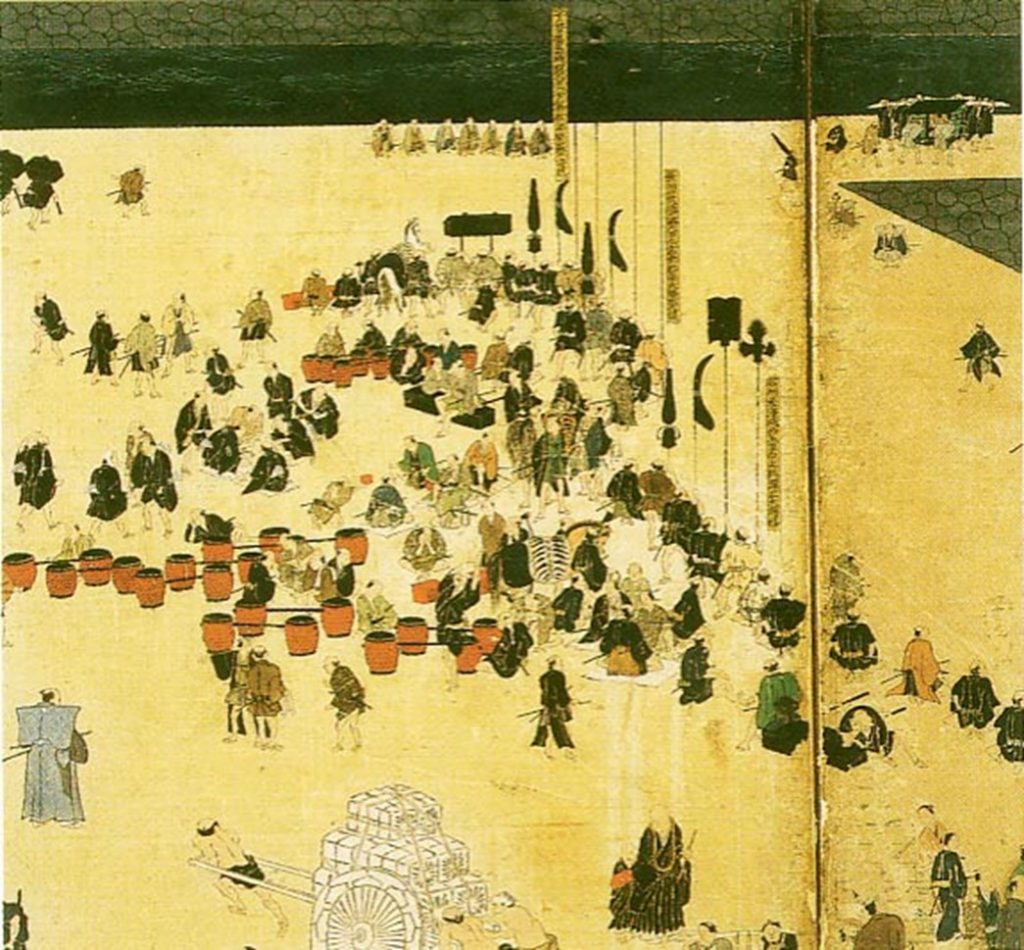

However, bukan was a special category of book that required long term observation of daimyo activities and constant update to the existing versions. There were several places in Edo that served as the spots where publishers could gather information for the making of bukan. We learn from some of the prefaces to bukan that one kind of such spot were places such as Ōtemon 大手門 and Uchisakuradamon 内桜田門 where daimyo and their retainers get off their horses before entering Edo castle .[13] Figure 11 is a visual depiction of the view of such a spot outside the castle. Such places provide plentiful of opportunities for the observers to identify the family crests, flags, the carryings and so on. In addition, they also collect information at the ceremonial days for the first three shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1543–1616), Tokugawa Hidetada 徳川秀忠 (1605–1623), and Tokugawa Iemitsu in the Tokugawa family temples in Edo, Kan’eiji 寛永寺 and Zōjoji 増上寺.

The Rivalry Between Suwaraya Mohē and Izumoji Izumi

After a century of development, most of the itakabu 板株 (publishing rights) of bukan were held either by Suwaraya Mohē or Izumoji Izumi. However, they both tried to monopolize the market by claiming the other to have violated their rights to the publishing rights. The conflicts and competitions between the two publishers were not limited to the two bookshops themselves but can be put under the larger conflict between Kyoto/Osaka and Edo publishers. In order to introduce the legal cases between the two, I shall briefly explain the bookshop association in Edo.

Bookshop association in Edo was established in Kyōhō 享保 6 (1721) consisted of three separate associations. Each association would have two gyōji 行事 (representatives) to jointly form a committee and decide various matters concerning publishing and censorship. These gyōji are selected from powerful members of the associations every two months. The three associations are named Tōrimachi-gumi 通町組, Nakadōri-gumi 中通組, and Minami-gumi 南組. The members of the first two associations are mainly Kyoto/Osaka publishers’ branch shops in Edo while the members of the last association are mainly publishers that founded their business in Edo. Izumoji belonged to Tōrimachi-gumi and Suwaraya belonged to Minami-gumi. As a Kyoto founded bookshop, Izumoji gained the support from both Tōrimachi-gumi and Nakadōri-gumi while Suwaraya was only supported by Minami-gumi. As I shall explain in the following paragraphs, Izumoji enjoyed an advantage in the committee of the Edo bookshop association in time when disputes between it and Suwaraya are brought to the association.

In addition to the advantageous position in the Edo bookshop association, Izumoji also enjoyed the prestigious title of goshomotsu-shi 御書物師 (official supplier of books to the shogunate). This official recognition of the shogunate provided Izumoji the opportunity to establish deep relationship with certain shogunal officials, and, as I shall demonstrate in the following paragraphs, it put Izumoji in an advantageous position in legal disputes with Suwaraya when they brought cases to the authority.

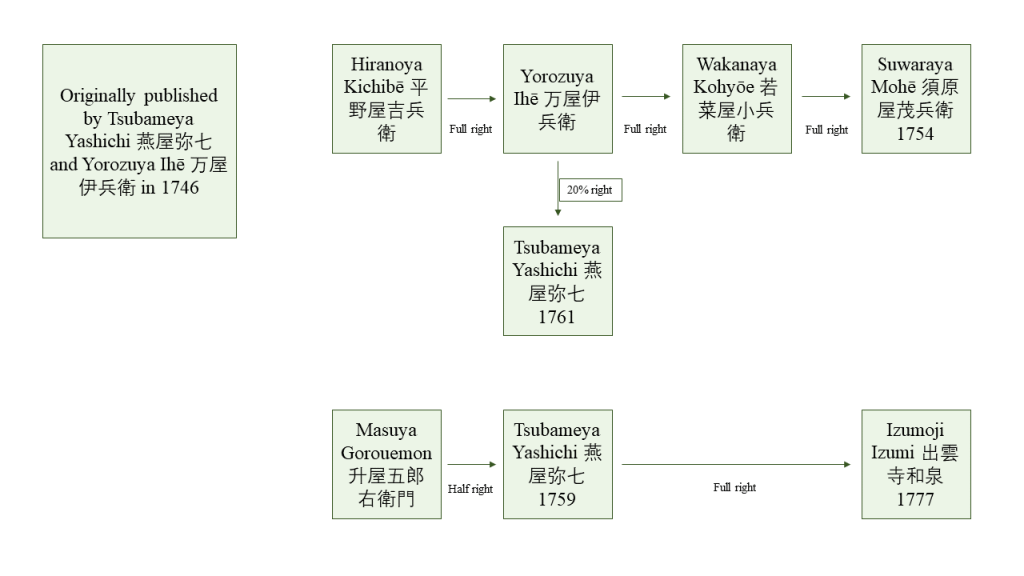

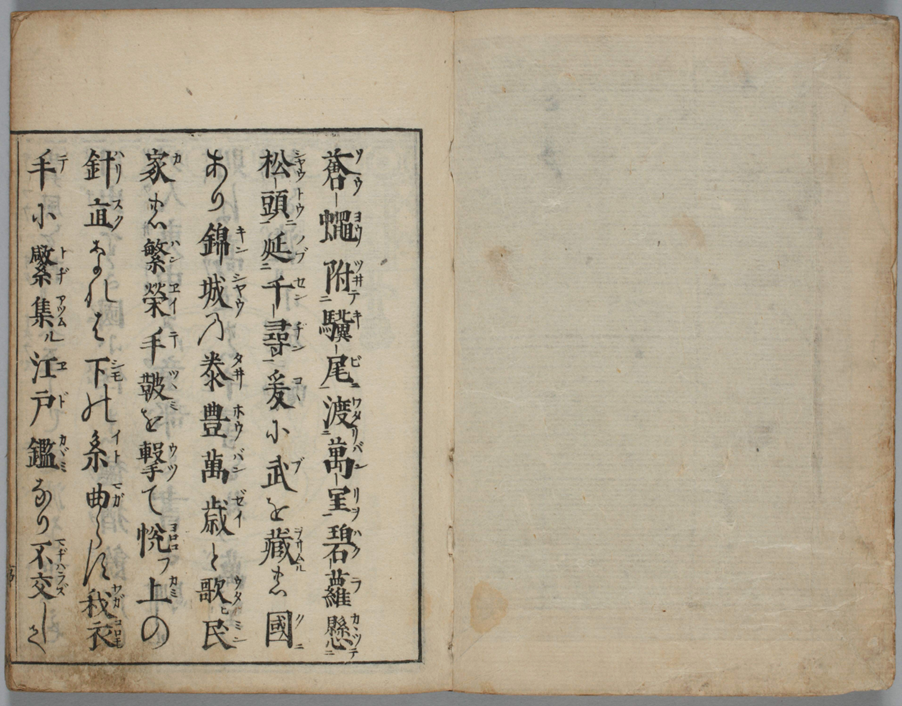

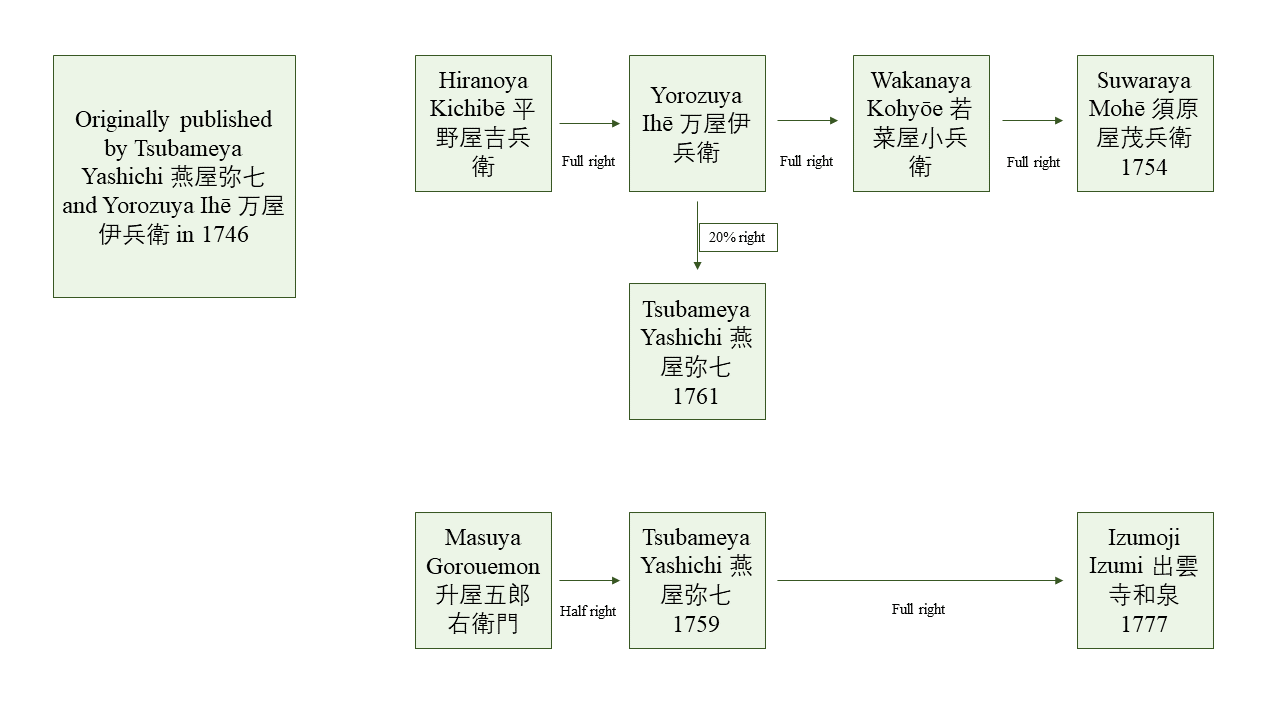

The dispute on the publishing right between Izumoji and Suwaraya on bukan begins in Hōreki 宝暦 9 (1759), when Izumoji planned to restart their publication of the four volume Taisei bukan 大成武鑑 (Complete Guide to Military Houses). Izumoji was the original publisher of Taisei bukan in Genroku 13 (1700), but it lost the ownership of itakabu of it during the Kyōhō era (1716–1736), and the right eventually went to Yorozuya Seihē 万屋清兵衛 during the Genbun 元文 era (1736–1741).[14] In Enkyō 延享 2 (1745), Tsubameya Yashichi 燕屋弥七 got the publishing right of Taisei bukan and reformatted it into a two-volume bukan titled Taisei ryaku bukan 大成略武鑑 (Brief Complete Guide to Military Houses) for publishing. Tsubameya then started to produce bukan in a smaller form with lesser content than the original Taisei bukan (see Figure 12). In 1759, Izumoji brought back the itakabu of Taisei bukan from Tsubameya and started to prepare the publication of the four volume Taisei bukan.[15] Suwaraya, upon hearing the news, visited Izumoji and asked them to stop preparing for the publication of Taisei bukan and promised that Suwaraya would cover the cost of the preparation if Izumoji would withdraw the publication. However, this proposal was rejected, and the matter was brought to the office of the Edo machi bugyō 江戸町奉行 (city magistrate of Edo). On the court, Suwaraya argued that because Tsubameya has changed the form and content of the original Taisei bukan into Taisei ryaku bukan, the original itakabu of Taisei bukan should be deemed as tsubure kabu 潰れ株 (destroyed publishing right), thus, the Izumoji’s future publication of Taisei bukan would become ruihan 類版, works that were partially or conceptually similar to another, which is an action prohibited by the shogunate.[16] On the other hand, Izumoji and Tsubameya insisted that Taisei ryaku bukan and Taisei bukan are two different books, so there is no issue for Izumoji to buy the publishing right of Taisei bukan and start printing it again. The ginmikata yoriki 吟味方与力 (police sergeants under the supervision of machi bugyō) responsible to this case decided that Suwaraya should provide historical examples to prove that the change of the number of volumes had invalidated the publishing right of the original version.[17]

The gyōji of the Minami-gumi and Suwaraya thus provided the evidence that the ginmikata yoriki requested as follow: first, there is the example of Kichimonjiya Jirobē 吉文字屋次郎兵衞 whose reformat of their Edo daiezu 江戸大絵図 (Great Map of the Edo City) into Edo koiezu 江戸小絵図 (Small Map of the Edo City) caused the invalidation of the itakabu of Edo daiezu; second, the committee of gyōji solely held the power in matters concerning the adding or reducing of volumes of books, but the reducing of the volume of Taisei bukan was not approved by the committee but by the machi doshiyori 町年寄 (town elders), which makes the process of reducing invalid; third, when Tsubameya changed the name of Taisei ryaku bukan to Taihei ryaku bukan 太平略武鑑 (n.d.) without the authorization of the Edo bookshop committee, it violated the regulation of the Edo bookshop association. The evidence was submitted to the ginmikata yoriki on Hōreki 9 (1759).11.3 but the ginmikata yoriki refused to take it since the document was only signed by the gyōji from Minami-gumi for which the ginmikata yoriki rebuked the gyōji of Minami-gumi and ordered him to get all the signatures of the other gyōji before coming back. At the second day, the gyōji of Minami-gumi discussed with the other gyōji and modified the second evidence. They agreed that although the process of reducing volume was problematic, since Tsubameya is not a member of the Edo bookshop association, it is acceptable that the application was sent to the office of machi doshiyori. However, when the modified evidence is brought to the ginmikata yoriki, the judgement was that Taisei bukan is a legal itabaku and there is no problem for Izumoji to republish it. Suwaraya is not satisfied with the judgement and appealed to the machi bugyō on Hōreki 9 (1759).12.6. The case is not handled by the machi bugyō until the spring of the next year. On Hōreki 10 (1760).6.1, the machi bugyō judged that Taisei bukan is a legal itabaku and there is no problem for Izumoji to republish it. However, the reduced two-volume itakabu of Taihei ryaku bukan is ordered to be classified as zeppan 絶板 (banned for publication).[18]

Evaluating the legal dispute between Izumoji and Suwaraya, Yayoshi Mitsunaga 彌吉光長 points out that: first, Izumoji is benefited from its official occupation of goshomotsu-shi and its connection with the officials in the shogunate that the process of the legal dispute and the judgement are all biased towards Izumoji; second, the committee of the Edo bookshop association is also clearly biased towards Izumoji in the process of ratifying the evidence.[19] Fujizane Kumiko, on the contrary, suggests that although the Edo bookshop association committee is biased towards Izumoji, the ginmikata yoriki and the machi bugyō are rather neutral and based their judgement on evidence. The favorable judgement towards Izumoji, according to Fujizane’s analysis, is based on the authority’s principle of highly valuing the views in the Edo bookshop association, where Suwaraya is not supported.

While Izumoji enjoys the support from both the shogunate and the Edo bookshop association, Suwaraya’s advantage lies in their consistent accumulation of the itakabu of bukan. In An’ei 安永 8 (1779), Suwaraya appealed to the Edo bookshop association accusing Izumoji to have violated the publishing right again. On Anei 8.6.28, Suwaraya found that Izumoji was planning to publish Taihei ryaku bukan. Suwaraya immediately contacted the Edo bookshop association to inquire the origin of Izumoji’s itakabu since the itakabu of Taihei ryaku bukan should already be classified as zeppan by the machi bugyō in the legal dispute between Suwaraya and Izumoji in Hōreki 9–10. Izumoji provided the evidence of the purchase of the itakabu of Taihei ryaku bukan and Seipo bukan 正宝武鑑 (Precious Guide to Military Houses) from Tsubameya Yashichi 燕屋弥七in An’ei 6 (1777). This is even more problematic for Suwaraya because Suwaraya had also purchased the itakabu of Seipo bukan from Wakanaya Kohyōe 若菜屋小兵衛 in Hōreki 4 (1754).[20]

In terms of the itakabu of Taihei ryaku bukan, the Edo bookshop association identified the original itakabu of Taihei ryaku bukan to be Taisei ryaku bukan that Izumoji purchased from Tsubameya in Enkyō 2 (1745) and showed the record of the purchase in the accounts book of Tōrimachi-gumi. However, since a previous fire had destroyed the accounts book of Minami-gumi, so Suwaraya could only rely on the record in the accounts book of Nakadōri-gumi, where no record about the transition of the itakabu of Taisei ryaku bukan. On top of that, Izumoji had managed to publish Taihei ryaku bukan during the investigation, so the Edo bookshop association decided to not further investigate into the matter since the book was already being sold on the market.[21] Again, the Edo bookshop association helped Izumoji in the publication of a zeppan book.

After the failed attempt to stop the publication of Taihei ryaku bukan, Suwaraya decided to focus on the issue of the dual ownership of the itakabu of Seipo bukan. The publishers and owners of the original itakabu of Seipo bukan were Yorozuya Ihē 万屋伊兵衛and Tsubameya Yashichi in Enkyō 3 (1746). Suwaraya could show their transaction record of Seipo bukan while the transaction record from Izumoji is suspicious. The suspicion of Izumoji’s record is, first of all, before Izumoji purchased the itakabu of Seipo bukan from Tsubameya, record shows that Tsubameya only purchased half of the itakabu from Masuya Gorōemon 升屋五郎右衛 (see Figure 13 for the full transaction route); and secondly, there is no signature of Masuya on the purchasing documents that Tsubameya provided. Thus, the association deemed that Izumoji’s itakabu of Seipo bukan to be problematic.[22]

However, Tsubameya argued that the section appears in Suwaraya’s Hōreki 11 (1761) Seidai bukan 聖代武鑑 (Guide to the Military Houses of the Holy Era) describing the toki genjō 時献上 (date for each daimyo to present gift to the shogun) was originally invented by Tsubameya in Seipo bukan in Enkyō 3 (1746), and, thus, Tsubameya requested the ownership of twenty percent of the itakabu. Suwaraya agreed on this term in order not to fall into a long-term legal dispute again, which could potentially allow Izumoji to lobby in the Edo bookshop association.[23]

In the two examples above, we can observe a close relationship between Izumoji Izumi and Tsubameya Yashichi as an independent publisher and a convenient partner to Izumoji. The transactions of itakabu between Tsubameya and Izumoji are not always clear, and since Tsubameya is not a member of the Edo bookshop association, some of the transactions are not clearly registered in the association. By utilizing the support and influence in the Edo bookshop association and the shogunate, Izumoji could play with the incomplete transaction records and successfully claim the ownership of some problematic itakabu.

Yayoshi Mitsunaga consider Suwaraya to have won a clear victory upon the matter of the itakabu of Seipo bukan.[24] His evaluation is based on the fact that Suwaraya had successfully prevented Izumoji from publishing a new format of bukan. It is indeed true that Suwaraya achieved the most important goal of the dispute. However, as Fujizane Kumiko points out, the victory is accompanied with compromise.[25] Suwaraya is forced to give up the full ownership of the itakabu of Seipo bukan in exchange of quickly ending the case.

The Success of Suwaraya Mohē

The category of bukan is always one focus point of Suwaraya Mohē’s business. The third generation of Suwaraya Mohē, Jigen 慈厳 (n.d.), is especially keen on purchasing itakabu of bukan from other publishers. Yayoshi Mitsunaga suggests that during the life of Jigen, Suwaraya purchased a total of eighteen itakabu of bukan from other publishers.[26] According to Suwaraya’s recording document, after Jigen, the only itakabu of bukan that is not purchased by Suwaraya is the two-volume Taisei ryaku bukan held by Tsubameya Yashichi.[27] The constant accumulation of itakabu has gradually allowed Suwaraya to monopolize the market.

The publishing of bukan is subject to monopoly. Fujizane Kumiko has compared the profit of bukan and ordinary literature books and concluded that the profit rate of ordinary literature books is 20 to 25 percent, about ten percent higher than that of bukan.[28] Therefore, there it is natural for those who wish to continue publishing bukan to try to achieve a monopoly of the market since the profit is not enough to support the additional work of information gathering. The purchasing of itakabu, by implication, would reduce the number of competitors, and, thus, it became the easiest way to increase the share of the market.

The competition between bukan publishers is intense in the early years of the Tokugawa period. One effort to compete with other publishers of bukan was to add a preface. In the late seventeenth and early eighteen centuries, when there are multiple publishers advocating their bukan on the market, prefaces are added to bukan in order to impress the customers.[29] Some of the prefaces insist on the accuracy of the content, some point out the fallacies of other bukan, and some employ a literary fashion to impress the customers. Figure 14 shows the preface to Hōei bukan taisei 宝永武鑑大成 (Great Collection of Guide to the Military Houses in Hōei Era), which includes a quotation from the Chinese classic Shiki 史記 to show the reverence to the Tokugawa shogunate. In the Kyōhō era (1716–1736), there is a period when Suwaraya is the only provider of bukan, and the bukan in this period are without preface. When Izumoji started to produce bukan again, Suwaraya immediately added preface to their bukan again.[30]

Suwaraya also benefited from constant publication of bukan in their publication of Edo maps. Suwaraya is also one of the most prominent publishers of Edo maps, and since the update of bukan requires long-term information gathering of the daimyo and high-ranking officials, for Suwaraya, the information about daimyo residence on the map is already there. Figure 15 shows a part of a map of the Edo city produced by Suwaraya. It can be seen that the name, family crest, location of daimyo residence is illustrated. These information needs constant update as well. The location of daimyo residence is not permanent in the Tokugawa period, some of the daimyo might be ordered to move their residence to another location in the city.[31] Therefore, the update of bukan and the update of the map of Edo could be benefited from each other. As two categories of tool publications, there is a constant need for both bukan and map. By monopolizing the market of bukan, Suwaraya not only gathered information for the updating of the map of Edo and also secured the stable profit of the selling of the map. As a result, Suwaraya achieved to reduce the cost for making both products and gained more profit out of them.

Suwaraya’s success could be largely attributed to their constant focus on accumulating bukan itakabu and the publishing of bukan. When they achieved the monopoly of the bukan market, it is hard for the newcomers to challenge them since the initial investment is too large for those who wish to start from scratch.

Conclusion

In the inner side of the back cover of the Shūgyoku bukan published by Suwaraya in Keiō 慶応 3 (1867).11, it says: “In the future, the publishing of bukan will be discontinued,” marking the end of Suwaraya’s bukan business.[32] In the last year of the Tokugawa period, many changes occurred. The discontinue of the publication of bukan is a rather small event and went unnoticeable for many. However, the discontinue of bukan captured one of the most fundamental change in the political system, and it symbolized the end of not only a regime, but, for many people after the Tokugawa period, a floating world called Edo.

Like the collapse of the shogunate, after the discontinue of bukan publication, Suwaraya lost the foundation of its business. Although it immediately asked for the permission to publish the Kan’in roku官員録 (Guide to the Government Officials) in Keiō 4 (1868),[33] Suwaraya was limited by woodblock printing technique. In the end, it was defeated by the movable type printing like most of the publishers in the Tokugawa period.

[1] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 178.

[2] In 1999, Fujizane Kumiko 藤實久美子 in suggests that the first known bukan is Gomonzukushi 御もんづくし, published in Kan’ei 21 (1644) by Sōshiya Kyūbee さうしや九兵衛; Fujizane, Bukan shuppan to kinsei shakai. She reported this newly discovered Godaimyō shū gochigyō jūmankoku made in her 2008 book, Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 69.

[3] The calling of daibukan was not limited to Suwaraya Mohē. It refers to the format of four-volume bukan in general. See Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 12.

[4] One koku of rice weighs 150 kilograms.

[5] Nishinomaru refers to an area southwest to the Edo Castle located in nowadays Hibiya 日比谷.

[6] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 13.

[7] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 182.

[8] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 182.

[9] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 31.

[10] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 215.

[11] Peter Kornicki provides a description of the process with all the Japanese terms for different professions. See Kornicki, The Book in Japan, pp. 47–48.

[12] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, pp. 178–81.

[13] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 192.

[14] Yayoshi, Edo jidai no shuppan, pp. 170–71.

[15] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, pp. 115–16.

[16] For Suwaraya’s accusation, see Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 116. For the definition of ruihan, see Kornicki, Book in Japan, p. 246.

[17] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 116.

[18] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, pp. 116–19.

[19] Yayoshi, Edo jidai no shuppan, p. 171.

[20] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 134.

[21] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 136.

[22] The content of this paragraph is extracted from Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, pp. 137–39.

[23] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 137.

[24] Yayoshi, Edo jidai no shuppan, p. 174.

[25] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 139.

[26] Yayoshi, Edo jidai no shuppan, p. 166.

[27] Yayoshi, Edo jidai no shuppan, p. 162.

[28] Fujizane, Bukan shuppan, p. 183.

[29] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 92.

[30] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 95.

[31] Examples can be found in Vaporis, Tour of Duty, chapter 5.

[32] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 221.

[33] Fujizane, Edo no buke meikan, p. 226.

References

Fujizane Kumiko 藤實久美子. Bukan shuppan to kinsei shakai 武鑑出版と近世社会. Tōyō Shorin, 1999.

Fujizane Kumiko. Edo no buke meikan ― bukan to shuppan kyōsō 江戸の武家名鑑―武鑑と出版競争. Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2008.

Kornicki, Peter F. The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century. University of Hawai‘i Press, 2000.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos. Tour of Duty: Samurai, Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008.

Yayoshi Mitsunaga 彌吉光長. Edo jidai no shuppan to hito 江戸時代の出版と人. Kinokuniya Shoten, 1980.