By Maya Suzuki Huisman

Introduction

The Yoshiwara district was the most famous pleasure district in Japan established in 1617 during the Edo period. Approximately 1,700 women (and some men) lived in this area when it was founded, but this soon grew to about nine thousand by the Meiji era. Some of the girls were as young as twelve or thirteen years old when they came to begin work in Yoshiwara.[1] Rapid expansion was due to heavy demand, and thousands of patrons frequented Yoshiwara on a daily basis. It is important to understand Yoshiwara in the context of the Edo and Meiji era Japan. These are periods in which urbanization was increasing, and therefore a concentrated population in the city of Edo, current day Tokyo, was rising. This led to the creation of districts such as Yoshiwara in order to provide pleasure services to the numerous men living in the area.

Yoshiwara’s social structure was rigid and hierarchical in nature. Women were highly categorized with specific labels that denoted their statues as a courtesan.[2] For men who were patrons, on the other hand, social status was less important within the wall of Yoshiwara, meaning that as long as a man had money, he was treated well by the women.

This project examines the ways in which women in the Yoshiwara district were viewed, and what their reality was actually like. To be more specific, in later years, there were many works of art, like paintings, prints and text, produced about these courtesans. The works portrayed the life of a courtesan/prostitute in the Yoshiwara district in the Edo period as a kind of beautiful dream that could lead to a greater possibility of living a peaceful life with a husband and family. However, life for these women was rarely that serene or simple.

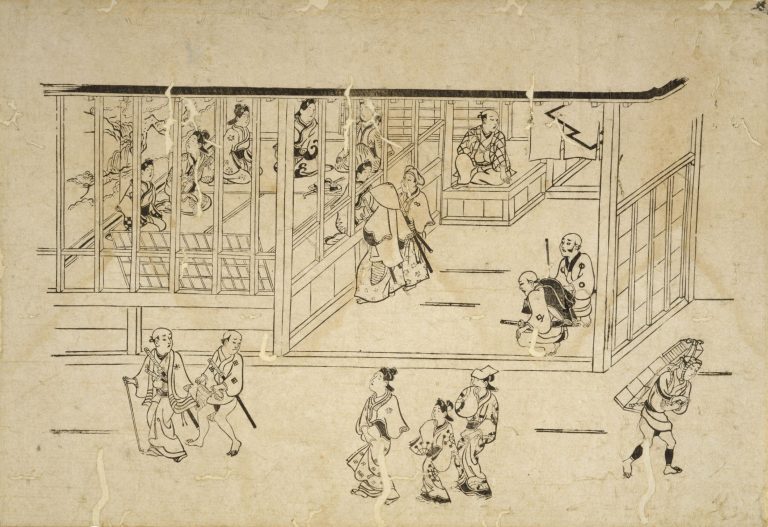

First, one must examine the art made of these women from Yoshiwara. Oftentimes these were woodblock prints that depicted ethereal women in beautiful natural settings. They were dressed in the most luxurious fabrics and were portrayed as relaxed. For example, Morunobu’s painting titled “A visit to Yoshiwara” made in the late 1690’s is a depiction of a lively street with women visible in their kimonos in the window of a structure. Other paintings depict the courtesans engaged with patrons in activities such as boating or displaying skills in music or performance. There are others that are simply showing the women’s faces (see Figure 1).[3]

After viewing these artworks, one envisions the mental image of a wonderful, dreamlike world where everyone is beautiful, happy and dressed well. There are several reasons that this is the particular image that Yoshiwara developed. First of all, many of these artworks were specifically commissioned by patrons of Yoshiwara.[4] This means that they would explicitly ask for depictions of their favorite women in the most flattering lights and clothing. Another reason why the artwork depicted women from Yoshiwara in this way is because they served as advertisements for brothels. When mass production became possible for art such as woodblock prints, brothels used this to their advantage. They began to create images that would entice men to come see the beautiful women in their specific brothel. This contributed to the general, high standard of beauty and perfection that all women in Yoshiwara were held to.[5] This inaccurate generalization also impacted those who did not visit the area.

Finally, famous works that were not advertisements or commissions were made by male artists. Why is this important? Because through the male gaze, Yoshiwara is a perfect illusion. The brothels and courtesans were perfectly orchestrated to put on a splendid show for any man who entered their premises. They would never peel back the mask of beauty and light-heartedness to reveal the ugliness within.

A man who entered Yoshiwara would only be shown the best aspects of it. The women will act and look as wonderful as possible in order to succeed at their jobs. This gives a completely inaccurate depiction of reality that a male onlooker would not be able to grasp.

Part II: Harsh Reality

The reality was that many of the women who lived and worked in the Yoshiwara district were sold into that life. Families who needed additional income could sell their daughters who were seen as less important than their sons. It is also important to note that as a paragon of filial piety some girls may have willingly offered or gone along with such arrangements in respect of their parents. There were also instances of handlers going out into rural areas that were experiencing hardship, e.g. due to natural disasters, in order to recruit and buy these daughters. By 1900, nearly half of the women from the Yoshiwara district came from households that were affected by severe natural disasters such as floods and crop failure.[6] This systematic buying and selling of daughters from poor countryside areas of Japan continued to increase the number of women in Yoshiwara. Once these girls were brought to Yoshiwara under the contract signed by the parents, it was difficult or impossible to repay the debts that they would accumulate. Due to this system, many scholars call the Yoshiwara a “near slave system”[7] where women would be forced to work for no pay until they died.

Conditions were less than ideal for courtesans. Depending on their rank, their access to hygienic and livable housing was different. Those at the very bottom, the prostitutes who worked on the sides of the moat, slept outdoors and were often malnourished. Even at higher ranks in the Yoshiwara social ladder, women still struggled to sleep enough, suffered physical abuse at the hands of men and were expected to look “perfect” at all times. Each station came with their own unique struggles, but what they had in common was the facade that all women in Yoshiwara put on for their male patrons. In order to make money, these women had to sell the “dream” of a beautiful woman who desired the male patrons.

Syphilis was a major killer of women in Yoshiwara during the Meiji period.[8] Many of these women suffered in silence as the disease overtook their bodies as not to break the beautiful image they tried to portray. Failed abortions also caused the death of a great number of women who did not have access to proper medical care[9] and needed to continue their profession in order to survive. Many of these women were brought to Jōkan-ji temple and buried namelessly because there was no money to afford a proper funeral.

Women in Yoshiwara were expected to behave and look in a certain way to achieve a specific trajectory. Many were hopeful to one day find a husband who would be able to take them out of the district and into a household. Marriage would be a path for these women to have their debts repaid and be able to leave work as a prostitute.[10] Though this did occur for some, it was not a realistic dream for most. Marriage was seen as the “ideal” for the women there, it was expected that they should aspire to be “rescued” from this profession by a male patron. This means that bodily autonomy for females was difficult to achieve, as a male was seen as integral for many decisions these women were given.

Part III: Higuchi Ichiyō

Many primary sources created during the Edo and Meiji period about Yoshiwara were written by men. This creates the issue that has been expressed earlier in this project, that the male gaze in this context was starkly different from reality. This is due to the numerous nuances and aspects of female life that many men during this time period would simply not be privy to. The writings of Higuchi Ichiyō are an interesting example of a female writer examining the lives of prostitutes during the Meiji Era. Coming from a poor family background, Higuchi was familiar with the struggles of those living in a lower-class environment.[11]

This clear divide between herself and her peers of the more upper-class households bolstered Higuchi’s interest in highlighting the lives of those less fortunate. When her family moved into a very poor area on the outskirts of the Yoshiwara district, Higuchi found inspiration and material to write about. Takekurabe, written in 1896, is a prime example of one of her works that highlights the life of those living in and around Yoshiwara.[12] This female’s view on other women allowed Higuchi to write a more accurate portrayal of those living around her. Higuchi herself was not among the clientele that the Yoshiwara women were trying to get money from. Also, Higuchi was in a better position to understand the position of limited power and self-autonomy that many women around her were experiencing.

Yes, it can be said that perhaps because of her background, Higuchi may not understand the complex nuances of being a courtesan, and also that she may have a bias against Japan’s social hierarchy in general which could cause her to paint women in a more sympathetic light. However, Higuchi’s works provide information closest to primary sources that scholars can research today. Many courtesans did not have the ability to write, did not have the time to do so, and would be outright discouraged from ever allowing evidence that would break the illusion of perfection of their seemingly beautiful existence.

Conclusion

Yoshiwara had two faces. The outward, artistic, and creative face was turned towards male patrons who sought, and found, the carefully constructed fabrication set up by the brothels and the courtesans. In this world, the women were beautiful and in love with them. They were dressed in beautiful clothing and displayed skills in music and acting. Women were to be saved by benevolent men, who, when they found the right woman, would take them into a life of peaceful domesticity. The artistic aspects served the ultimate purpose of creating sensual pleasure for individuals who could afford to patronize Yoshiwara. The inward, destructive face of Yoshiwara reflected the reality of women who worked day and night in an unforgiving environment. Immense pressure to be perfect, coupled with the physical dangers of abuse, malnutrition, and venereal diseases were deadly for many of the women who lived there. Little hope of marriage was the prospect of the courtesans who were sold by their families, sometimes as an act of filial piety, into a system that would keep them until the required money to be released was paid. Yoshiwara forced women into a decided trajectory of climbing the ranks of courtesans, with the end goal of marriage to entice them to become more productive and sensual prostitutes.

This is not to say that every courtesan’s life was a tragic tale of woe; there were certainly tales of triumph and happiness as well. This project is highlighting is the antimony that the lives of most of these women represented: living in two worlds that each had their truths and laws, but also contained irreconcilable contradictions. These contradictions consisted of having to show the highest forms of artistic human behavior while being subjected to the lowest forms of human behavior themselves. The women were held to the highest standards of skills and beauty for the pleasures of men. Their own reality was the subjugation and loss of bodily autonomy. They spent their lives serving the needs of first their fathers, then the men paying for their services, and finally, if they were lucky, a husband.

While there were certain truths in each of the two worlds of Yoshiwara, one can argue that the truth surrounding the outward looking artistic face is more contentious, particularly when depicted as an art form, through paintings, prints and texts, in later years. The art of the courtesans was not produced as a common good but served the more limited private interests of individuals, for a single commercial purpose. In that regard, perhaps one could call a courtesan’s appearance and performance more a work of advertisement than a work of art. It is also questionable whether a society should consider a certain appearance or performance a work of art when the negative emotional and physical effect on the performer ultimately outweighs the positive effect on the recipient of the performance. There are irreconcilable differences between these realities, yet women working in Yoshiwara were expected to blend the two into a cohesive, functional entity. How many women were triumphant in gaining control of their bodies and therefore their lives? Was this reserved for only the highest-ranking Orin who could choose their clientele to a certain extent? How many women questioned this system? How many rebelled? These are questions that sadly do not have the primary source evidence to be satisfactorily answered but should leave historians and readers of this page wondering.

[1] Rogers 1994, p. 504.

[2] Helgadottir 2011, p. 35.

[3] “Supplement: Exhibition Labels: Designed for Pleasure: The World of Edo Japan in Prints and Paintings, 1680-1860,” p. 170.

[4] Hix, “Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan’s Floating World,” Collectors Weekly, 2015.03.23.

[5] Stanley 2013, p. 539.

[6] Lindsey 2011, p. 6.

[7] Narayan 2016, p. 2.

[8] Burns 1998, p. 4.

[9] Narayan 2016, p. 2.

[10] Stanley 2012, p. 541.

[11] Tanaka 1956, pp. 171-90.

[12] Helgadottir 2011, p. 9.

Bibliography

Burns, Susan. “Bodies and Borders: Syphilis, Prostitution, and the Nation in Japan, 1860–1890.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement 15 (1998), 3-30.

“Supplement: Exhibition Labels: Designed for Pleasure: The World of Edo Japan in Prints and Paintings, 1680-1860.” Japanese Art Society of America, Impressions 30 (2009), 168–203.

Helgadottir, Svanhildur. “Pleasure Women: Court Ladies, Courtesans and Geisha, as seen through the eyes of female authors.” B.A. Thesis, University of Iceland, 2011.

Hix, Lisa. “Sex and Suffering: The Tragic Life of the Courtesan in Japan’s Floating World.” Collectors Weekly (2015.03.23). Retrieved from https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/the-tragic-life-of-the-courtesan-in-japans-floating-world/.

Lindsey, William R. Fertility and Pleasure: Ritual and Sexual Values in Tokugawa Japan. University of Hawai’i Press, 2007.

Narayan, Saarang. “Women in Meiji Japan: Exploring the Underclass of Japanese Industrialization.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 8:2 (2016), 1-3.

Stanley, Amy. “Enlightenment Geisha: The Sex Trade, Education, and Feminine Ideals in Early Meiji Japan.” The Journal of Asian Studies, 72:3 (2013), 539-62.

Stanley, Amy, and Sommer, Matthew. Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan. University of California Press, 2012.

Tanaka Hisako. “Higuchi Ichiyō.” Monumenta Nipponica 12:3/4 (1956), 171–94.

Rogers, Lawrence. “Review of Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan by Cecilia Segawa Seigle.” Monumenta Nipponica 49:4 (1994), 503–506.