By Mikaela Li Ane Phang

Introduction

This project will give the reader a short introduction to the origins of women’s magazines in Japan, particularly in its relation to women’s education and enlightenment (as they were materials for the early female reader), and discuss the types of magazines that were available from the late Taishō to early Shōwa period. I discuss how women’s magazines have consistently reflected what was popular at the time and how those trends have changed since their beginnings. I aim to introduce the target audience for these magazines and the influence of the magazine content to the reader before giving a summary of what the media form has turned into today.

The origins of Japanese women’s magazines can be traced back to the turn of the 20th century,[1] when publishing houses started to use the marketing practices of dividing potential readers by age, gender, education, and interests etc., in order to create a variation of magazines to cater to different parts of society. This coincided with a large transformation of the role, status, and image of women. With the start of women’s magazines came the influx of images of women at home, work, and outside, which showed the different variations of women’s lives.

These magazines seemed to serve two purposes. One, being the media form responsible for socialising women into the Japanese philosophy of ryōsai kenbo (“good wives, wise mothers”), which, even until today, continues to represent the image of the ideal Japanese woman.[2] This can be seen in the example of the magazine Jogaku Sekai (女学世界, “World of a Woman Student”), which included fiction, but heavily focused on pastimes such as tea ceremony and waka poetry. Its aim was to “supplement those areas lacking in women’s education today” and to “cultivate wise wives and good mothers.”[3]

The second purpose concerned their commercial use, and how the magazine relies on women to read, participate, and act as consumers for the contents of the magazine.

Popular magazines in the late Taishō period

For the approximate twenty years from 1911 to 1930, over two-hundred women’s magazines and journals were established in Japan. This rise was attributed to the rising levels of education, income, and urbanisation that had diversified and expanded the potential number of readers. The Taishō period was a significant era for women, a time when the roles of women also diversified in society. Because of the rapid progress of industrialization and development of the higher education system for women, more educated women were being produced and this increased the number of educated women participating in the workforce as professionals (shokugyō fujin).[4]

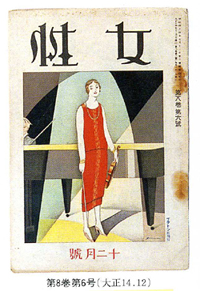

In the late Taishō era, more women began to discuss women’s rights issues such as equal employment, suffrage, and birth control. This differed from early women’s reading materials in Japan, in which the main goal was just to educate women into their more stereotypical roles of how to behave as a woman. Many of the ‘new women’ of this era cut their hair short and wore western-style dresses. These magazines did not just educate socially and politically; they also encouraged women to be active consumers in Japanese society. This time period also saw the creation of magazines with entertainment news, similar to what is found in today’s weekly women’s magazines. Because women had a wider range of lifestyles, opinions, and viewpoints in this period compared to the women in previous times, who had little choice but to marry and raise children as their main goals, magazines such as Josei 女性 (“Woman”) and Fujin kōron 婦人公論 or “Women’s Review,” very much suited the needs of the women and reflected the changing trends of the time. The creation of mass magazines reflected both the wider growth of the culture of the emerging “new women” and the expansion of women’s education.

The target markets of these magazines were the rapidly increasing numbers of well-educated middle and upper class women due to the industrialisation and urbanisation of this time period, though these were not the only women who found themselves reading these magazines.[5] In looking at the social and cultural construction of a new set of possibilities for female behavior, women’s magazines effectively served as a force in the creation of new identities for Japanese women in the 1920s. The target demographic of women’s magazines was the middle class or above, “who were married to salaried businessmen and government officials,” – the suburban housewife who “centred her consumption on the home and the well-being of her husband and children,”[6] as those were the women who could afford to live the lives reflected in the magazines. However, because of efforts made to increase the spread and circulation of the media, even women who were not all too familiar with books subscribed and became frequent readers, as they were able to access information about modern lifestyles different from their own. As such, women’s magazines not only served as the foundation for shaping a mass culture for middle-class readers in women’s society, but to a slightly lesser extent also played a part in the formation of new identities for lower-middle-class and working-class women.[7]

The contents of the magazine Josei, in particular, reflected the diversity of issues faced by women and the complexities of the Taishō democratic society into the early Shōwa period. Topics ranged from major political issues of suffrage, birth-control, and escaping the ideals of the family unit framework, to issues more connected to everyday life, such as the transition from wearing a kimono to a more modern day dress. The magazine also gave women an opportunity to discuss and question private issues related to love, marriage, and motherhood, but on a more public scale outside of the inner circle of housewives, which offered new ways for women to consider and think about their lives.[8]

The magazine Shufu-no-Tomo 主婦の友 [Companion of Housewives], first published in 1917[9], had a conservative stance and addressed young married women, covering topics about home management, savings, and birth control. Its target audience was the mass market and middle-class women, and was also one of the most popular magazines of the time. The magazine sold more than one million copies for every issue since 1934 until it ceased production in 2008.[10]

How magazines changed and compared to early eras

Magazines such as Fujin kōron, a journal of opinions concerning women’s issues which was created in 1916, played a part in the elevation of women’s status in Japan. Fujin kōron was originally published in a special issue of Chūōkōron 中央公論 (“Central Review”), which is a type of monthly magazine referred to in Japan as sōgō-zasshi, “integrated intellectual magazines” or “composite magazines.” Throughout their history, Chūōkōron have specialized in writing about the main issues in Japan’s leading political, social, and cultural aspects, and as such, mirror the history of Japanese modern society in those times. By shedding light on women’s issues the increased media attention placed greater importance on women in society and contributed to the elevation of the status of women in Japan as a result, at least in regards to political involvement.[11] This development shows that while women’s magazines were originally created and spread in order to educate or shape the Japanese woman to follow the image of an ideal wife or mother, the purpose of the magazine changed in later eras to motivate women to participate in society and to think for themselves politically and socially.

In terms of statistics, the actual circulation data of many publications cannot be stated with accuracy up until the late 1920s due to lack of data. Former magazine editor, Hashimoto Motomu, wrote in his book on the history of publishing industries in Japan that the three top-selling magazines at the time were women’s magazines, each with double the circulation of the intellectual magazine Chūōkōron. Annual circulation surveys from a major subscription agent, Tōkyōdō, show that women’s magazines were the most popular magazine genre from 1929 to 1934, and even after that they sold as much as other popular magazines, showing that the popularity of women’s magazines in Japan continued well into the 1930s. For example, data for 1934 shows the annual circulation of top magazine genres: women’s magazines 19,750,000, popular entertainment magazines 18,740,000, boys’/girls’ magazines 9,740,00, children’s magazines 7,480,000, magazines concerning politics, economics, arts, or sciences 4,270,000, and youth magazines 2,180,000.[12]

What was the impact of magazines on Japanese women and society?

These women’s magazines effectively reflected the trends of the time. The way media works, as shown in the past, is that circulation effectively works in a cycle. As something becomes a popular topic it is written about in the media, and as the media reaches more readership the topic becomes more popular. This can be said in the case of Japanese women’s magazines in the early eras as well.

More specifically, starting from the Taishō era, the women’s magazine industry grew greatly. After the launch of Shufu-no-Tomo in 1917, the mass-market women’s magazine became accepted and acknowledged as a distinct magazine genre. After the end of the First World War (1914–1918), people’s needs for more practical information about a more “economical” and “rational” modern lifestyle grew. As the nation’s economy recovered, and the incomes of most people in urban areas increased, mass-market women’s magazines shifted their emphasis on “frugality” in economics, to “wise consumption,” straight to “consumption,” which partly came under the influence of the already present consumerist culture from the West (of the modern girl and Americanisation). The circulation of women’s magazines continued to increase in this period, and as a result the 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of modern consumerism in Japan, and essentially functioned as one of the main trendsetters during that time.

Magazines of this time (Taishō) represent the rise of the group of “new women” who demanded not only their political rights, but freedom from the long-established lifestyle of the household (ie) system. Through the content published through the magazine Josei that ran from 1922 to 1928 during the peak of Japanese modernism,[13] it was possible to see the values held by the typical lady (fujin) gradually loosen, with more women beginning to find their own identity as ‘women,’ separate from men. These magazines opened up the discussion floor to allowing women to talk about politics, their private lives, and own issues more openly. The magazines also inviting a new lifestyle based on consumerism,[14] which would later largely contribute and lead to the formation of modern consumer culture in Japan as we know today.

Conclusion – Magazines in today’s Japan

In terms of content, many women’s magazines are now based on lifestyle and consumption, containing information about fashion trends, restaurants and food, and cultural events, though there are still some magazines, such as Keiko to Manabu ケイコとマナブ, that provide information about schooling, education, languages, technological know-how, etc. There are also magazines available for more specific topics related to running households, such as the use of electrical appliances and the storage of items in small Japanese homes.

Nowadays, most magazines are largely made up of elaborately designed visual elements such as photography and manga, as well as eye-catching advertisements for items such as branded clothing and cosmetics as opposed to previously utilized large blocks of plain text.

Though similar to the past, the main types of women’s magazines still belong to two categories: education and lifestyle. The way in which these magazines affect and influence their readers is also similar. Educational magazines that write about useful tips and information in regard to running households can easily influence women in their consumer decisions. Magazines that focus on lifestyle are mostly filled with expensive brand goods that most of their readers want but may not be able to afford. Despite this fact, readers can still view these magazines as a source of inspiration and may be able to find a cheaper substitute instead.

Magazines are generally seen as a form of entertainment. The content of magazines does not necessarily just give information and influence consumer decision making, but can also act as a temporary diversion from everyday life and responsibilities.[15] Though mass women’s magazines had their basis in a patriarchal system, to continue to associate them with established routines and gender conventions downplays their change in ideological and economic complexities.

Mass women’s magazines became a place where women could partially redefine their roles and use their provided information as a gauge to test change, in a way that would influence women’s lives and partially contribute to the movements of feminism.[16]

In conclusion, magazine themes of the past have mostly remained unchanged from their growth in the Taishō and Shōwa eras, as they still divide into the topics of education and lifestyle. The magazines encouraged consumerism, but the specific contents have changed reflective of the times and advancements in society. Magazines of today are still being influenced by, as well as influencing, trends and female readers’ thoughts.

[1] Assmann, “Japanese Women’s Magazines: Inspiration and Commodity.”

[2] Sato and Wöhr “Japanese Women’s Magazines: Between Indoctrination and Pleasure, Intellectual History and Popular Culture,” paragraph 1.

[3] Sato, “Gender, Consumerism and Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan,” p. 40.

[4] Ishii, “Josei: A Magazine for the New Woman,” paragraph 1.

[5] Ishii, “ Josei: A Magazine for the New Woman,” paragraph 5.

[6] Assmann, “Japanese Women’s Magazines Inspiration and Commodity,” paragraph 6.

[7] Sato, “Gender, Consumerism and Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan,” p. 39.

[8] Ishii, “Josei: A Magazine for the New Woman,” paragraph 47.

[9] Masahide, “History of Magazines in Japan.”

[10] Maeshima, “Women’s Magazines and the Democratization of Print and Reading Culture in Interwar Japan,” p. 4.

[11] Kondo, “The Development of Monthly Magazines in Japan,” paragraph 8.

[12] Maeshima, “Women’s Magazines and the Democratization of Print and Reading Culture in Interwar Japan,” p. 4.

[13] Ishii, “Josei: A Magazine for the New Woman,” paragraph 1.

[14] Ishii, “Josei: A Magazine for the New Woman,” paragraph 28.

[15] Assmann, “Japanese Women’s Magazines Inspiration and Commodity,” paragraph 3.

[16] Sato, “Gender, Consumerism and Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan,” p. 49.

References

Assmann, Stephanie. “Japanese Women’s Magazines Inspiration and Commodity.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 2003. Retrieved from here.

Masahide Kanzaki. “History of Magazines in Japan,” 1996. Retrieved from here.

Ishii Kazumi. “Josei: A Magazine for the ‘New Woman’.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context 11 (2005). Retrieved from here.

Kondo Motohiro. “The Development of Monthly Magazines in Japan”. The Journal of Japanese Society for Global Social and Cultural Studies 1:1 (2004), 1–9.

Maeshima Shiho. “Women’s Magazines And The Democratization Of Print And Reading Culture In Interwar Japan.” PhD dissertation, The University of British Columbia, 2016.

Sato, Barbara. “Gender, Consumerism and Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan”. Routledge Handbook of Japanese Media, ed. Fabienne Darling-Wolf, 39–50. London: Routledge, 2018.

Sato, Barbara and Wöhr, Ulrike. “Japanese Women’s Magazines: Between Indoctrination and Pleasure, Intellectual History and Popular Culture.” International Symposium in Europe 1997 (2000), 1–13.