By Ayano Soma

Introduction

Today, the vast majority of men and women in Japan are dressed in yōfuku, or Western clothes, such as suits, sweater, T shirts, and jeans. It is rather rare to see someone dressed in the traditional Japanese clothes such as kimono, yukata and hakama except for occasions like summer festivals, the coming-of-age ceremonies, and university graduation ceremonies. Nonetheless, the prevalence and popularity of Western clothes is hardly a recent event; in fact, the shift toward Western clothes from Japanese clothes became universal for people in Japan after the 1970s.[1] During this transition period of fashion between the Meiji period and Shōwa period, men and women also went through a transition of social and cultural customs as well as gender roles. Among these changes, this research will especially focus on the changing everyday clothes of common women from kimono to jeans and aims to examine the advancement of women’s rights in this period of time reflected in the changing trends of fashion beginning with the adoption of Western clothes by the upper class during the Meiji period, followed by the increasing prevalence of Western clothing among common people during the Taishō period, which led to its nationwide popularity during the Shōwa period and the prevalence of Western clothing in contemporary Japanese fashion.

Fashion and Gender Roles

To begin with, the relevance of fashion to gender roles should be established. Joanne B Eicher and Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins argue that one dresses in the appropriate way for their sociocultural system that they are in, and therefore political, social, and cultural insights of a group of individuals can be drawn from the common fashion that can be seen among them.[2] Gender roles is one of those insights, and the authors argue that it is very much relevant to dress.[3] In the work, the term dress is classified into two categories: body modification, including change in hair, skin, and nails, and body supplements, including enclosures, attachments, and hand-held objects, both of which are used together to express their personality, identity, and gender.[4] The choice of dress, therefore, can help analyze the sociocultural role that the individual or the gender is in at that particular time. As an example, Eicher and Roach-Higgins introduce the instance of changing fashion of women in white-collar jobs in the 1960s in the United States; as the ideology of economic equal opportunity for women and men advanced, they started to wear tailored business suits which had previously been linked with masculinity and men later began to adopt more bright colors and soft fabrics which had been associated with femininity.[5] Hence, examining the transition of how women dressed not only provides the historical background but also the key to understanding the gender role, or in other words, women’s social status and advancement at that time.

Meiji Restoration

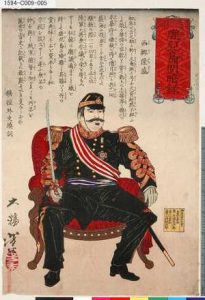

Following the Restoration of the Imperial Rule in 1867, the Edo period came to an end and the new era of Imperial Meiji government initiated. One of the top priorities for the new government was to establish the modern state to catch up with the growing powers abroad. Fashion was one of the various things that the Meiji government eagerly adopted from the West. To realize that, the emperor stated there would be a change in manners and customs in September 1871, and issued a law regarding formal dress in November 1872.[6] Sakurai Yasuko argues that one of the earliest onsets of the new fashion took place in the military which was in the process of modernization, where they directly imitated the military uniform from England and France, which can be seen worn by the famous former samurai warrior Saigō Takamori (Figure 1), and also as a uniform in the new public industries such as post and transportation.[7]

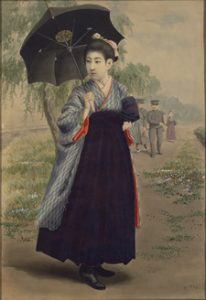

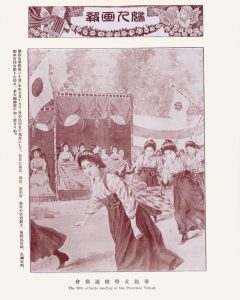

On the other hand, the prevalence of women wearing expensive Western clothes took much longer, with the exception of those from upper class or high education background and those who returned from the West. Figure 2 shows the countess of Ogasawara Nagayoshi, Earl of Kokura, The reason why Western clothes were not accepted among common women as soon as it did among common men, in addition to the unbalanced proportion of people engaged in occupations who were them as a uniform, was the uncomfortable Victorian style of clothes worn in places like the Western styled social club Rokumeikan, an example of which can be seen in the picture of the dress (Figure 3) and the famous ukiyo-e painting[8] (Figure 4).

The change in how jogakusei was not limited to dress; they also cropped their hair short and posed like men, suitable to the masculine clothes they put themselves in. Rebecca Copeland argues that this was due to their determination to compete against the male counterpart for desired educational opportunities.[10] The public, however, did not take this imitation well; newspaper articles called them indecent and absurd and they unfortunately became the object of ridicule.[11] Although small groups of women started to have equal opportunities in some fields, the public was yet to be willing to accept the change.

Taishō Democracy and Kantō Great Earthquake

After about four decades of restoration, Taishō period began with the fall of the Meiji Emperor. One notable feature of this period is what is called Taishō Democracy, a series of civil rights movements for a more liberal and democratic society. Female liberation movements were also prominent in this period and were led by feminists such as Hiratsuka Raichō and Ichikawa Fusae. Despite the ongoing campaign for equal opportunities for women, even the female activists who were seen as the radical, new women still were dressed in Japanese clothes.[12] According to Ōiwagawa Futaba, all the female participants of a feminist seminar held in 1919 were dressed in Japanese clothes, while half of the male participants were dressed in Western clothes.[13] However, the female activists finally came to be exhausted from moving around all day in the rather unfunctional Japanese clothes and decided to try Western clothes.[14] This event was recorded in the diary of the New Women’s Association, a women’s rights organization founded by Hiratsuka, Ichikawa, and Oku Mumeora, “1st of July, I, Hiratsuka, begin wearing Western clothes as of today,” in reference to the navy blue serge suit that she had a “teacher of Western sewing who returned from America” sew.[15] Ōiwagawa Futaba suggests how revolutionary this transition must have been to have indicated the precise day on which the event occured.[16] In fact, the picture taken at the first general meeting of the New Women’s Association in the following year shows Ichikawa in a suit surrounded by other members in Japanese clothes (Figure 7). Although modern Western clothes were still very rare for women to wear, they began to be recognized as work clothes by activists in this era.

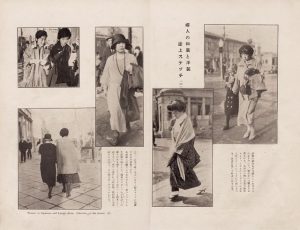

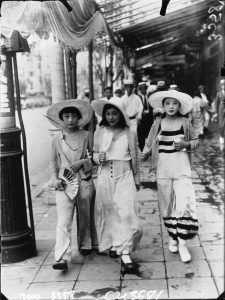

Another noteworthy event that happened in this era is the Kantō Great Earthquake took place on 1 September 1923. Ōiwagawa argues that the teito fukkō, roughly translated as imperial capital reconstruction, that was implemented in response to this disastrous incident spurred the Westernization of the city.[17] Women’s fashion was no exception to this Westernization, and the popularity of Western clothes spread outside the circle of pioneering female activists. Several sewing schools teaching how to sew Western clothes opened in Tokyo toward the end of the Taishō period and the beginning of the Shōwa period, and the research conducted in Tokyo by Reiwa Jirō shows that the ratio of women dressed in Western clothes jumped from a mere 1 percent in 1925 to 16 percent in 1928.[18] Although Western clothing was not a common style of dress yet, it slowly but surely was becoming less rare for women in the city to wear Western clothes (Figure 8).

Epilogue

In the period of about 150 years since the Meiji government promoted Westernization in the name of modernization until today, the clothes men and women in Japan wear have changed slowly but tremendously. The adoption of Western clothes took place from the rich to poor, from men to women, and from city to countryside. With the efforts made by female activists such as Hiratsuka, women today stand more politically, socially, and economically equal to men than ever, and that is reflected in the gender-free fashion that is commonly seen in recent years. Nevertheless, dress is yet to be completely free from gender biases even to this day. A new term sōshoku kei danshi, quite literally translated as herbivorous boys, emerged referring to men who dress or behave in a softer way to distinguish them from the strong and masculine, in other words carnivorous, traditional image of men (for Figure 11 please click here). If women were to dress in more revealing clothes, media often labels them as too sexual or at times even promiscuous (for Figure 12 please click here). Dress is a significant tool that has been used to examine culture and customs, including gender relations, throughout the course of history.

[1] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 249.

[2] Eicher and Roach-Higgins, “Definition and Classification of Dress: Implication for Analysis of Gender Roles,” p. 22.

[3] Eicher and Roach-Higgins, “Definition and Classification of Dress: Implication for Analysis of Gender Roles,” p. 8.

[4] Eicher and Roach-Higgins, “Definition and Classification of Dress: Implication for Analysis of Gender Roles,” pp. 15–19.

[5] Eicher and Roach-Higgins, “Definition and Classification of Dress: Implication for Analysis of Gender Roles,” p. 22.

[6] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 233.

[7] Sakurai, “Nihon ni okeru yōfuku juyō no katei: Meiji zenki,” p. 2.

[8] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” pp. 234–235.

[9] Sakurai, “Nihon ni okeru yōfuku juyō no katei: Meiji zenki,” pp. 7–8.

[10] Copeland, “Fashioning the Feminine: Images of the Modern Girl Student in Meiji Japan,” p. 15.

[11] Copeland, “Fashioning the Feminine: Images of the Modern Girl Student in Meiji Japan,” p. 32.

[12] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 237.

[13] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 237.

[14] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,”pp. 237–238.

[15] Hiratsuka in Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 238.

[16] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p, 238.

[17] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 239.

[18] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 239.

[19] Anzō and Koizumi, “Modan gāru ni miru fukushoku bunka,” p. 98.

[20] Kitazawa in Anzō and Koizumi, “Modan gāru ni miru fukushoku bunka,” p. 103.

[21] Davis in Silverberg, “After the Grand Tour: The Modern Girl, the New Woman, and the

Colonial Maiden,” p. 357.

[22] Iwashita in Anzō and Koizumi, “Modan gāru ni miru fukushoku bunka,” p. 108.

[23] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 243.

[24] Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 243.

[25] Management Coordination Agency in Ōiwagawa, “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made,” p. 244.

References

Anzō Yūko 安蔵裕子and Koizumi Makiko 小泉真貴子. “‘Modan gāru’ ni miru fukushoku bunka” 「モダン・ガール」にみる服飾文化. Gakuen kindai bunka kenkyūsho kiyō 学苑・近代文化研究所紀要 815 (2008), pp. 98–115.

Copeland, Rebecca. “Fashioning the Feminine: Images of the Modern Girl Student in Meiji Japan.” U.S-Japan Women’s Journal 30/31 (2006), pp. 13–35.

Eicher, Joanne B. and Roach-Higgins, Mary Ellen. “Definition and Classification of Dress: Implication for Analysis of Gender Roles.” In Dress and Gender, ed. Ruth Barnes and Joanne B. Eicher, pp. 8–28. Berg Publishers, 1993.

Silverberg, Miriam. “After the Grand Tour: The Modern Girl, the New Woman, and the

Colonial Maiden.” In The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, ed. Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger and Madeleine Yue Dong, pp. 354–61. Duke University Press, 2008.

Ōiwagawa Futaba 大岩川嫩. “Nihonjin to yōsō: Rokumeikan kara onna ga jīnzu o haku made” 日本人と洋装: 鹿鳴館から女がジーンズをはくまで. In “Kimono” to “kurashi”: Dai-san sekai no nichijyōgi 「きもの」と「くらし」: 第三世界の日常着, pp. 232–51. Institute of Developing Economies, 1993.

Sakurai Yasuko 桜井保子. “Nihon ni okeru yōfuku juyō no katei: Meiji zenki” 日本における洋服受容の過程: 明治前期.” Chūgoku tanki daigaku kiyō 中国短期大学紀要 13, (1982), pp. 1–13.