By Rio Shimizu

Introduction

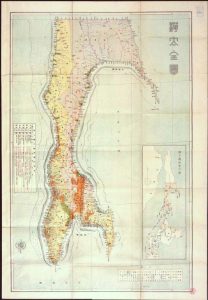

Sakhalin Island, which is located at the Eastern coast of Eurasia and north of the Japanese island Hokkaido, has a long history of Russia and Japan competing for its ownership—its Japanese name is Karafuto. In 1905, after signing the Treaty of Portsmouth, which entailed the end of the Russo-Japanese War, South Sakhalin was governed under the Empire of Japan. Unlike other Japanese colonies such as Korea and Taiwan, the number of original inhabitants was smaller and the overall population of Sakhalin formed a large number of Japanese immigrants, 95 percent of its population.[1] Among the rest of the population, half of it was Korean immigrants who mostly came in after 1938 and engaged in simple physical labor. The overall population of Karafuto reached 380,000 in 1945. Nevertheless, the number of Japanese people in Sakhalin greatly decreased after the end of World War II. Most of the ones left behind in Sakhalin were women who later intermarried with Koreans. This paper explores the factor behind the intermarriages by focusing on their status as women and their ethnicity as Japanese. Moreover, the influence of intermarriage on their repatriation will be discussed. This research proceeds with three parts. Firstly, the historical background of Japanese women left behind in Karafuto will be discussed with particular focus on the invasion of the Soviet army in South Sakhalin. The latter part of the paper will examine the factor behind the intermarriage with Koreans and its influence on repatriation.

The historical background of Japanese women left behind in Sakhalin

One of the key historical events that led to the mass evacuation of Japanese people to their homeland was the invasion of the Soviet army in South Sakhalin. Until the Soviet Invasion, South Sakhalin was a peaceful island that faced minor impact during the World War II. Yet, on 11 August 1945, South Sakhalin was invaded by the Soviet Union, which had abandoned the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact to join the war against Japan.[2] South Sakhalin was suddenly turned into a battlefield and many civilians became embroiled in the war. The Soviet attack lasted on, even after the end of World War II, and it was over by the end of August. The sudden invasion of the Soviet Union led to a mass evacuation of Japanese people and Koreans to Hokkaido from August 13. Nakayama argues that the first wave of mass evacuation with a number of people fleeing to Japan of about 90,000, and later a total of 24,000 Japanese and Koreans smuggled themselves to Hokkaido. However, this emergence of evacuation came to an end on August 23 when the Soviet army attacked three evacuation ships of Japan and closed down the Sōya Strait. Through this stop to the evacuation, about 270,000 Japanese and 23,000 Koreans were left behind in Sakhalin. The first official repatriation movement was carried out from 1946 to 1949,conducted by the Soviet Union and the United States. Since Japan was unable to have a direct negotiation with the Soviet Union through diplomatic channels, the negotiations concerning the repatriation of Japanese civilians were conducted by these two countries.[3] The subjects of repatriation were Japanese civilians, prisoners of war, and Koreans who were born and had lived in North Korea above the 38th parallel before.[4] The North Koreans would be repatriated from Japan to North Korea.[5] Through this second wave of mass evacuation, most of the Japanese repatriated to their homeland. However, even after the official repatriation movement, about 1,400 Japanese were left in Sakhalin, they were mostly women. Many of them had married Koreans in between the emergence evacuation and the first repatriation movement and that intermarriage made it difficult to return to Japan during the first repatriation movement.

The number of Japanese women’s intermarriage with Korean men

According to Hyun and Paichadze, the number of Japanese women who married Korean men exceeds that of those who married Russian men. This can be seen by viewing the “The Register of Pure Japanese,” which shows the number of Japanese living in Sakhalin. The register covers 173 people (thirty-nine men and 134 women), who were born between 1908 and 1946.[6] Among the 134 Japanese women, about seventy-seven women had either a Korean family name or a full Korean name. About twenty-nine Japanese women changed only their family name to a Korean name which can most likely be explained by intermarriage with Korean men. One of the factors of changing their names was due to fear of their origins being discovered and facing discrimination within the Korean community and being accused of espionage. Though some of the fear factors might had led them to changing their names completely, it did not apply to everyone. Viewing intermarriage with Russian men, the number of Japanese women having a Russian family name was only fourteen. Thus, it can be ascertained that more Japanese women married Korean men than Russian men.[7] In the next part, the factor of Japanese women who intermarried with Koreans will be discussed by first focusing on the characteristics of Koreans who shared similar features with Japanese women.

The characteristics of Korean men in Karafuto

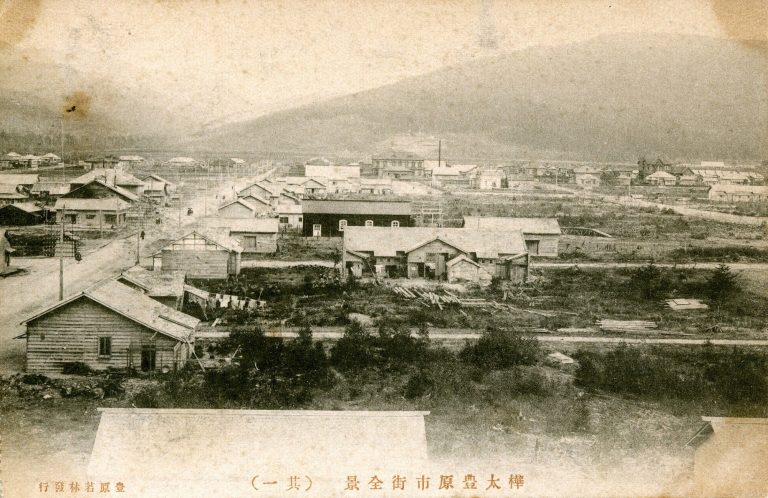

Similar to the women left behind in Sakhalin after the first repatriation movement, a large number of Koreans were also left behind in August 1949.[8] Koreans living in Sakhalin at that time were mainly from South Korea and they were forcibly brought in as labor force in 1938 , engaging in physical labor such as working at coal mines. Although the number of Korean immigrants in Karafuto had greatly increased after Japan’s proclamation of the National General Mobilization Law in 1938,[9] many Koreans had already arrived in Sakhalin before the forced mobilization of labor from colonial Korea.[10] In fact, 4387 Koreans lived in Sakhalin in December 1926. Among the Korean immigrants, the number of single men was much higher compared to its immigrant families. As Choi points out, they relocated to Sakhalin by their own will to seek a better life. Since Karafuto was formed with a large number of Japanese before the Soviet Invasion, the Koreans also spoke Japanese. This linguistic aspect probably fostered the interaction with Japanese people and influenced the number of intermarriages with Japanese women.

The factor of intermarriage with Korean men: status as women and ethnicity as Japanese

In fact, Japanese women who were left behind in Sakhalin show commonalities with Koreans in terms of social class. The Japanese in Sakhalin were also poor people who were looking for a better life and therefore moved to a new land, Karafuto. According to Tominari and Paichadze, they were mainly poor farmers from Hokkaido and the Tohoku region. Unlike the Japanese people in Taiwan and Korea who were oftentimes white-collar workers, Japanese people in Sakhalin were also engaged in general labor, for instance fisheries and farming. Both Japanese and Koreans moved to Sakhalin to seek a better life in the new environment and they were close to each other in terms of low socio-economic status. Moreover, their ethnicity as Japanese serves as another factor of intermarriage with Koreans. In fact, many Japanese men died in the war and some of them returned to Japan without their families after World War II.[11] The condition of Japanese single women and single mothers in the postwar situation presented itself to be even more difficult than the pre-war situation, especially for the single mothers who needed help in raising children due to economic hardship. Hyun and Paichadze introduced a Japanese woman whose mother married a Korean man after her Japanese father died in 1947. The situation that her mother was facing, left with six children in a very difficult situation, led to marriage with a Korean man because of economic necessity. Since there was a small number of Japanese men in Sakhalin, it was more likely for Japanese women to marry Koreans in terms of the large number of single men, similar socioeconomic status, and ability to speak Japanese.

In addition, in postwar Sakhalin, the number of Koreans was much higher than that of Japanese, and Japanese women were absorbed into Korean community. Although the interaction between Japanese and Koreans had existed before the war, it intensified after the war. So, the number of postwar marriages between Japanese women and Korean men far exceeded the number of pre-war marriages.[12] Nevertheless, the mixed formation of Korean and Japanese families is often considered a forced marriage. Yoshitake argued that the factor of intermarriage was due to parents’ fear that their daughter would be sexually abused by the Soviet army unless they marry. Furthermore, some Japanese women were intimidated by Koreans who were angry about their pre-war treatment. In the chaotic situation of postwar Sakhalin, fear might have led to forced marriages, but as Hyun and Paichadze illustrated, not all marriages were by force. The love and mutual benefit led to marriage in many cases, too.[13] Moreover, the similar social condition and shared language may also have led to the increase in intermarriage with Koreans.

Influence of intermarriage on repatriation movement

However, the intermarriage made it difficult for Japanese women to repatriate, especially with the official repatriation movement which was carried out between 1946 and 1949. Since the subjects of repatriation were either Japanese civilians, prisoners of war, or North Koreans, many of the women whose husbands were originally from South Korea were not included in the repatriation program and were not allowed to get on the repatriation ship.[14] Similarly, children with Korean fathers were not considered subjects of the repatriation. As a result, Japanese women had no choice but to give up on their own repatriation since they could not return without their Korean husband and children. Yet, after the Soviet-Japan Joint Declaration of 1956, the second repatriation program was conducted between 1957 and 1959. At this time, Korean men who intermarried with Japanese women were recognized as Japanese citizens and were able to return to Japan.[15] Through this repatriation movement, 766 Japanese women and their Korean husbands and children (1,541 in total) returned to Japan.[16] Nonetheless, some Japanese women were still left behind in Sakhalin even after the second repatriation program. According to the Japan-Sakhalin Association, one of the reasons was due to disagreement by their husbands about returning to Japan. Furthermore, on some occasions, Japanese women decided to stay in Sakhalin as their husband was not able to return to his homeland, South Korea, thus they also decided not to return to Japan.

Repatriation after the second repatriation movement

Though intermarriage once affected their early repatriation in the first repatriation movement, there was a smaller impact on the latter repatriation program which was conducted between 1957 and 1959. Nevertheless, intermarriage seemed to have had an impact on the repatriation of Japanese women due to the possibility of families being separated. In other words, concern for their husband and children made it difficult for Japanese women to leave their family. Therefore, there seemed to be some women who remained in Sakhalin by their own will regardless of having the opportunity to repatriate. Yet, during the 1960s to 1990s, there was movement of Japanese people between Sakhalin and Japan in terms of individual return. According to Tominari and Paichadze, about 100 Japanese returned from 1963 to 1994. From the late 1980s, the public organization Karafuto Dōhō Ichiji Kikoku Sokushin no Kai (the predecessor of the Japan-Sakhalin Association) attempted to find out about the remaining Japanese in Sakhalin, and supported their temporary return in the 1990s and their permanent return from 1992.[17] After the enactment of 中国残留邦人等の円滑な帰国の促進及び永住帰国後の自立の支援に関する法律 (The Law regarding the Promotion of Smooth Return of Japanese Remaining in China after World War II etc. and Support for their Independence after the Permanent Repatriation) in 1994, the return of second and third generations of remaining Japanese became possible and the repatriation movement from Sakhalin became full-fledged. Until the 2016, 104 households (275 people) repatriated permanently to Japan, many of them settled in Hokkaido.[18] In addition, Korean people, other than those who married Japanese women, also were able to return to Korea after the repatriation movement conducted by the South Korean government around 1990. By the end of 2000, 1,352 Sakhalin Koreans had returned. [19]

Conclusion

To sum up, South Sakhalin, whose population used to consist of a large number of Japanese people, decreased in population after the invasion of the Soviet army in South Sakhalin. Although several repatriation programs were conducted, most of the Japanese people who were left behind in Karafuto were women who intermarried with Koreans after the war. Many of the Korean immigrants were originally from South Korea. The large number of immigrants was brought into Sakhalin in 1938 as labor force. Meanwhile, there were already some Korean men who came to Sakhalin before the forced immigration from colonial Korea, to seek a way to make a living in a new land. Similarly, Japanese women in Sakhalin also moved to South Sakhalin seeking a better life. One of the factors of their intermarriage was the similar socio-economic status, the large number of single Korean men, and their ability to speak Japanese. Moreover, the presence of single mothers had an impact on the number of marriages in terms of economic necessity to raise their children. However, Japanese women who intermarried with Korean men faced difficulty regarding their repatriation. Due to their husbands who were mostly from South Korea and who were not included as subjects of repatriation, Japanese who intermarried with Koreans were also left behind in Karafuto. Though some of the Japanese women were able to return to Japan with their husbands and children in the later repatriation program, some of them chose to stay because of concern about the separation of their family. Also, there were some Japanese women who were not able to return to Japan due to disagreement by their husband. The chaotic situation of postwar Sakhalin might have led to intermarriage with Koreans as a form of forced marriage. Yet, the similar characteristics between Korean men and Japanese women and economic necessity might have been the main factor that accelerated their marriages, and there seemed to be love between them as some decided to stay in Sakhalin to not separate the family.

[1] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā,” p. 6.

[2] Tonai, “Soviet rule in south Sakhalin and the Japanese community, 1945–1949,” p. 80.

[3] Tonai, “Soviet rule in south Sakhalin and the Japanese community, 1945–1949,” p. 94.

[4] Japan-Sakhalin Association, “Saharin to Nihon”.

[5] Choi, “Forced migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and their repatriation,” p. 119.

[6] Hyun and Paichadze, “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin,” p. 203.

[7] Hyun and Paichadze, “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin,” p. 204.

[8] Nakayama, “Zanryū Nihonjin to wa dare ka: Hokutō ajia ni okeru kyōkai to Kazoku,” p. 24

[9] Choi, “Forced migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and their repatriation,” p. 115.

[10] Hyun and Paichadze, “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin,” p. 199.

[11] Hyun and Paichadze, “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin,” p. 202.

[12] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā,” p. 8.

[13] Hyun and Paichadze, “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin,” p. 202.

[14] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā,” p. 7.

[15] Choi, “Forced migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and their repatriation,” p. 121.

[16] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā,” p. 7.

[17] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā,” p. 7.

[18] Tominari and Paichadze, “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā, p. 8.

[19] Choi, “Forced migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and their repatriation,” p. 130.

References

Choi, Ki-young. “Forced migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and their repatriation.” Korea Journal, 44:4 (2004), 111–132.

Hyun, Mooam and Paichadze, Svetlana. “Multi-layered Identities of Returnees in their ‘Historical Homeland’: Returnees from Sakhalin.” In Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese border, ed. Svetlana Paichadze and Philip Seaton, 195–211. London: Routledge, 2015.

Ido Masae 井戸まさえ. “‘Musume ga shinda toki, washi wa odotta:’ Saharin de ikiru zanryū Nihonjin no kokuhaku” 「娘が死んだとき、ワシは踊った」サハリンで生きる残留日本人の告白. Gendai Business, (2018.08.16).

Japan-Sakhalin Association 日本サハリン協会. “Saharin to Nihon” サハリンと日本. http://sakhalin-kyoukai.com/history/index.html (2020. 07.05).

Nakayama Taisho 中山大将. “Zanryū Nihonjin to wa dare ka: Hokutō ajia ni okeru kyōkai to kazoku” 残留日本人とは誰か: 北東アジアにおける境界と家族. The proceeding of Kyoto University-Nanjing University Sociology and Anthropology Workshop 2013 (2014), 22–27.

Tominari Ayako 冨成絢子 and Paichadze, Svetlana. “‘Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen’ (Yoshitake Teruko-chō) ni miru minzoku to jendā”『置き去り-サハリン残留日本女性たちの60年』(吉武輝子著)にみる民族とジェンダー. The Journal of International Media, Communication, and Tourism Studies 28 (2019), 3–20.

Tonai Yuzuru. “Soviet rule in south Sakhalin and the Japanese community, 1945–1949.” In Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese border, ed Svetlana Paichadze and Philip Seaton. pp. 80–100. London: Routledge, 2015.

Yoshitake Teruko. 吉武輝子. Okizari: Saharin zanryū Nihon josei-tachi no 60-nen. 置き去り: サハリン残留日本人女性たちの六十年. Kairyūsha, 2005.