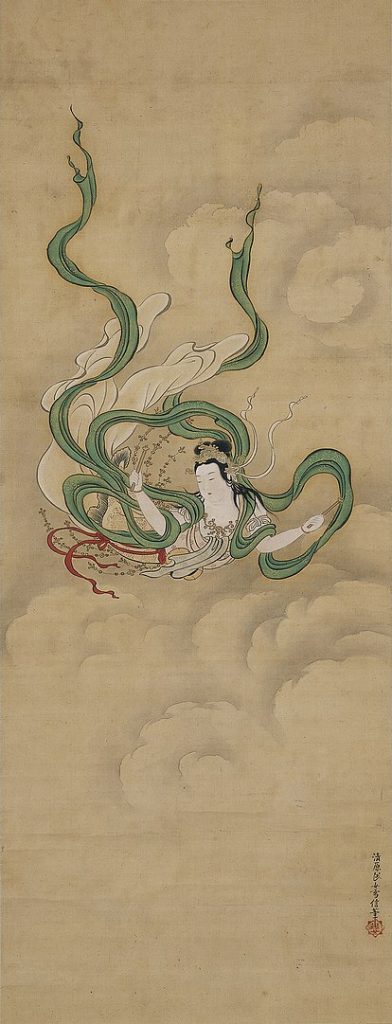

It is noted that in the early modern period, there was a relative scarcity of professional women painters, due to their exclusion from male dominated studios; an exception to this would be Kiyohara Yukinobu (1643-82), a professional painter from the seventeenth century who likely had access to her own creative space. She was related to the celebrated Kanō Tan’yū (1602-1674), who founded the Kanō school, the official place of painting instruction for the Tokugawa shogunate, famously originating the shin-yamato-e painting style, distinguished by illustrating iconic scenes from traditional Japanese stories and implementing a soft colour palette. Yukinobu often depicted female figures, Buddhist icons, shin-yamato-e content, and natural scenery such as flowers and birds (a trend brought from China to Japan in the 1730s by Shen Nan-p’in (1682-1760)) all of which were popular themes at the time. In particular, Flying Celestial (latter half of the seventeenth century) and her works depicting Murasaki Shikibu were very characteristic of female produced artwork from this era, due to the religious overtones. Yukinobu is interesting due to her proclivity for painting female subjects. The depiction of women through a female gaze is historically significant, providing the viewer with a glimpse of Japanese women’s lives during the Edo period. Yukinobu preferred to focus on poets and figures of historical significance. As Fister notes, “women artists’ admiration for and identification with female subjects differ from men;”[1] the way in which women portray other women in art is less focused on surface-level aesthetics, but rather deeper psychological meaning. For example, one of Yukinobu’s most iconic pieces is her illustration of the classical tale Makura no Sōshi, in her work depicting Sei Shōnagon. To paraphrase Fister, the focus is not entirely on the figure of the woman, and her physical appearance is not emphasised; rather the focal point of the illustration is the tale itself, and a depiction of the narrative as a whole. Yukinobu’s fascination with feminine storytelling is further supported by her creation of a piece depicting thirty-six famous woman poets; as Yukinobu consumed poetry written by women, it is expected she would honour them within her own work.

[1] Fister 1997, p. 7.