By Mana Nomoto

and Miu Sera Yokoyama

The following text is part of a presentation that is available here.

Introduction

Icons serve as role models to influence the general public, while also illustrating the desired star persona according to the demand of the time period. After the traumatic loss in the Second World War, under the Occupation of the U.S., the Japanese national identity was shaken. With the homeland occupied by the enemy and American reformations of national moral codes, the people of Japan began to seek traditional “Japaneseness” within the cinema industry. Focusing on the early postwar period, between 1945 to 1950s, this project explores the effect of Japan’s defeat in World War II that had led to the re-emphasis of traditional values onto popular female actresses (icons) in the cinema industry at the time.

Icons and Persona

“Icons implies repetition of both form and content.”[1] For many actresses, their iconic figures were created and embedded in the society by repeating to play similar roles in films with similar narrative. Another way icons and persona of popular actresses were established was through evaluation by the public audience of films. Repetition indicates the popularity of the context and the attractive characteristics of Japanese women presented by the cinema industry through actresses. The importance of repetition is its role in intensifying response to stimuli.[2] Thus, actresses’ repetition of similar roles definitely played a part in implementing popular icons. Here, it is important to recognise that those iconic characteristics of popular actresses that will be introduced in this paper do not coincide with the essential national identity of being Japanese. Rather, this essay is going to illustrate those characterisations of actresses by the cinema industry as a fantastical construct by society, public and the government. Therefore, those constructs of icons in early postwar reflect the national public discourse of Japan.

In addition, it was and still is important that star personas of actresses must identify with “us”— thus typical women.[3] The strong sense of typicality was essential for the iconic figures to appeal to the audience, especially during the chaotic period of early postwar period.

The importance in understanding the construction of icons and star persona provides a holistic perspective in demonstrating Japan’s attempt to protect the national identity and coherence between pre-war period and postwar period. According to Coates, in the early postwar period, the coherence in actresses’ persona with the general public, national identity and historical continuity was a form of reassurance that reconstruction of “coherent self” is not impossible.[4] The next section will further discuss the impact of the defeat Japan experienced in the early postwar period and how that shook the identity of “Japaneseness.”

Postwar Japan

Officially signing the Tripartite Pact in 1940, Japan fought in the Second World War for five years alongside the Axis powers of Germany and Italy. As Japan both attacked and were attacked by the nations of the Allies, the destruction of the war had resulted in a dire situation for the civilians in Japan. With basic needs in short supply and the constant fear of air raids, the devastating atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the news of Japan losing the war were the final tipping points for many Japanese at the time. Known as kyodatsu, the term refers to the total physical and mental collapse of a person, which was a condition many Japanese people at the end of war experienced.[5] After surrendering to the Allies in 1945, Japan was under the Allied Occupation that was predominantly managed by America.

The kyodatsu condition after the devastating defeat and being under the Occupation by the enemy forces had shaken the sense of nationalism and comradeship that were previously established in the minds of the Japanese people at the time. Under the U.S. Occupation, the Japanese were encouraged to fit into the Western and American ideals. The replacement of the Japanese values advanced into various elements within the lives of the Japanese people as America took it upon themselves to “liberate” Japan. One of such liberations included the reform of traditional principles placed on women. As Mark McLelland states, the U.S. Occupation authorities were keen to change the “feudalistic customs, attitudes and practices”[6] in Japan at the time. Nevertheless, the changes made by the Occupation authorities were by no means complete liberation of women from gender roles. In fact, both the Japanese officials and the U.S. authorities encouraged the role of a woman as a married mother who is also a worker contributing to the social life within Japan.[7]

Around the early postwar period, a new type of subculture had emerged known as kasutori. This underground literary culture influenced the birth of literary genres, such as nikutai bungaku (literature of the flesh) that featured writings about physical, often sexual, desires.[8] According to Joseph Yamagiwa, the rise in the appeal for sexual expressions resulted from the notion within writers that “flesh was the only reality in life” after war.[9] In addition, the loss of furusato (“home”) due to the incorporation of Western ideals within Japan after the war had evoked a feeling of homelessness among Japanese citizens as they became estranged from the nostalgic environment in pre-war Japan.[10] Thus, the influences of the U.S. Occupation and the newfound subcultures that had emerged from the damages after the war had left many Japanese citizens to desire the return of ‘Japaneseness.’ Consequently, the repulsion against Western influence resulted in the manifestation of traditional values through female icons in various entertainment mediums–— here, in this project, specifically in cinema.

Westernization in early U.S. Occupation: peoples’ reactions to American liberations

Misora Hibari – early career

Video 1: Misora Hibari performing Hoshi no nagare ni (“In the Flow of the Stars”), in 1949 at the age of 12 (00:00:48).

Misora Hibari’s career started at the young age of eleven years. Many of her early performances on stage included the imitation of adult women in a sexualized manner. With her unique singing voice, charisma and her benefitting from the kasutori culture at the time, which favored sensual performances, Misora quickly rose to fame in the performance industry.

One example of Misora being presented in a sexual way is in the song Hoshi no Nagare Ni (“In the Flow of the Stars”). The song is about a female prostitute, known as part of the “pan-pan girls,” and she begins the performance by pretending to smoke. “Pan-pan girls” are street prostitutes that appeared around the period of U.S. Occupation. They are defined as “prostitutes who violated the conventions of a well-ordered sex industry by selling sex in the open.”[11] Unlike the transitional prostitutes confined to brothels, “pan-pan” gained economic power and the status of cultural icons. “Pan-pan girls” were admired for their autonomy that women in Japan never possessed before. They lived freely with money they earned and enjoyed material comfort brought by their American clients. Although many communities in Japan gradually began to criminalise solicitation and thus resulted in the fading of the power and popularity of “pan-pan girls”, they were remembered as a part of the cultural figure of postwar Japan.

Traditional Japanese-ness vs. Americanisation (Westernisation) in Early Postwar Japan

Although the period of U.S. Occupation inevitably “Americanised” Japan, the inter-war period from the 1920s to the 1940s was also significant in modernising and Americanising the nation.[12] After the First World War, Japan as well as many other countries were exposed to the American virtue of freedom and its popular culture. Hollywood films were especially an effective means of expanding American culture.[13] By the 1920s, Japan began to import many luxurious U.S. goods, and consumerist lifestyles emerged in upper-middle to high social class. However, as the war between Japan and China intensified from the late 1930s, the Japanese government began to reestablish its nationalistic virtues. Japan as a nation began to criticize foreign influences, especially of Americans, in an effort to shift the focus of the traditional Japanese moral code.[14] This rise in hostility towards Americanisation persisted until the early postwar era, and is apparent and reflected in the public view towards female celebrities. Here, examples of Tanaka Kinuyo are going to demonstrate Japan’s attitude towards Americanisation and the traditional Japaneseness.

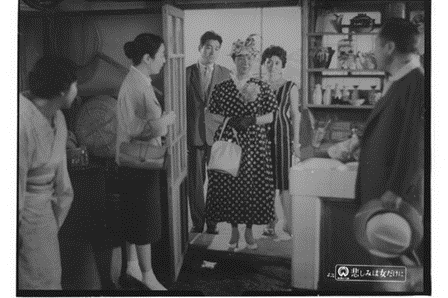

In early postwar Japan, Tanaka Kinuyo, who was considered a veteran in the Japanese film industry, was criticised by the media and her fans for her “Americanisation” after her trip to America in the 1950s.[15] Coates refers to Satō Tadao’s analysis on Tanaka’s following Japanese traditional women roles as an attempt to gain back popularity from the audience. The post-war Japanese identity crisis led to the revaluing of traditional “Japaneseness” and the viewer and the media began to impose the ideal to Japanese female celebrities. However, in 1958 director Shindō Kaneto decided to take advantage of Tanaka’s uncherished image in Kanashimi wa onna dake ni (“Only Women Have Sadness”). Tanaka played a comical role of an aunt visiting Japan from the United States who teaches others English inspirational quotes and thoughtlessly inquires about the aftermath of the atomic bomb. Unlike in 1950, when Tanaka’s association with America was criticised by the public, by 1958 the audience accepted this illustration of Westernised women and viewed it as comical.[16] This portrays a shift in the general public’s attitude towards the war and America in less than a decade as well as illustrating the fluidity of a star persona. As society’s popular demand shapes stars’ persona, it is bound to shift as time passes. Thereby, around 1950 the strong demand of the public for pure-“Japaneseness” led to Tanaka playing more roles as women wearing kimono to disassociate her image of Westernisation, whereas the public’s reevaluation of attitude towards the United States shifted the persona of Tanaka Kinuyo.

The Return of Japaneseness

Misora Hibari – Shift into Adulthood

While Misora Hibari’s stardom started off with the controversies surrounding the sexualisation of young children, the shift away from such association with sexuality came about in the film Kanashiki Kuchibue (“Sorrowful Whistle”), released in 1949. Unlike her stage acts in previous years, which sexualized Misora as a child, the film represented her in an innocent light by casting Misora as a war orphan.[17] This change of act re-established Misora as a child-like, innocent celebrity, in stark contrast to the adult-like, scandalous stage acts she used to perform. In this way, films played a large role in the change of Hibari’s persona as a star.

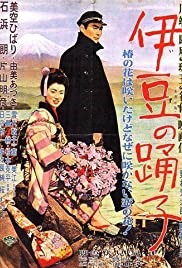

One prominent film which came to define the normative image of Japanese girls is Izu no odoriko (“The Izu Dancer”). Originally a short story by Kawabata Yasunari, there are multiple film and television adaptations that came about after the initial publication of the novel in 1926. The plot of the story is centered around a young male university student from Tokyo, Mizuhara, who is travelling around the Izu Peninsula. Along his journey, Mizuhara encounters a small troupe of travelling performers. As he continues his travels in Izu with the troupe, he eventually falls in love with the dancer named Kaoru, however, their relationship remains strictly as friends and the two eventually bid farewell as he separates from the performing troupe to return home.

In the post-war adaptation of the film in 1954 starring Misora Hibari, the character of Kaoru “hardly speaks, never smiles, and remains physically still” throughout the film.[18] This tamed characterisation of the character Kaoru is especially in sharp contrast to the pre-war adaptation of the film in 1933, Koi no hana saku: Izu no odoriko (“Flower of Love in Bloom: The Dancing Girl of Izu”), starring Tanaka Kinuyo. In Takana’s version, Lauri Kitsnik analyzes Kaoru to have a “childlike behaviour” that is expressive and mobile in space as she is portrayed to be an otenba (“tomboy”).[19] Accordingly, the two contrasting adaptations of the film illustrate the change in representation of women. In the case of the 1954 film, the film makers strived to re-establish the morals of traditional Japanese values by idealizing an obedient and submissive woman through the icon, Misora Hibari.

Hara Setsuko as Eternal Virgin: Ideal female figure and Divinisation of Female Star

Hara Setsuko, whose career began in 1935 at the age of fourteen, was a well-known actress known as “eternal virgin” (永遠の処女- Eien no shojo), depicting a pure and innocent image. Her nickname came from the role she often played that portrayed a woman who is reluctant to marry. One of the most well-known films that illustrates this star persona is “Late Spring” (晩春 – Banshun) directed by Ozu Yasujirō in 1949. In this film Hara plays the role of a woman who doesn’t want to marry as she fears to leave her father alone, presenting an ideal image of a loving and caring daughter.

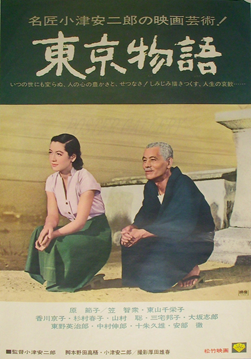

Another example is “Tokyo Story” (東京物語 – Tōkyō monogatari), also directed by Ozu in 1953, in which Hara again portrays a similar “saint-like” good woman.[20] The film is about an elderly couple who visits Tokyo to meet their children who are too busy and careless to make time for their parents. Noriko, played by Hara who is a widowed daughter in law to the parents, is the only one who tries to entertain them.

The consistency in roles that Hara played during the early postwar period depicts the popular ideal of Japanese women of the time. The image of saintly kindness demanded by the public towards female actresses presents a similar virtue from principle of filial piety in Confucianism. The virtue of filial piety entails to be respectful to one’s parents and engage in proper conduct to establish a good reputation for one’s parents. Japan’s hostility towards Westernisation, that is apparent in earlier portrayals of Tanaka Kinuyo, may have led to Japan turning towards more familiar and traditional values of Chinese Buddhism to battle the time of uncertainty during the early postwar period. Moreover, Jennifer Coates suggests that Hara’s innocent image as an eternal virgin was popularised by men who felt threatened by the Westernisation of women.[21]

One important film that portrays Hara’s virtuous image is called Nippon tanjō (lit. “The Birth of Japan”) directed by Inagaki Hiroshi in 1959. Hara’s virtuous star persona was depicted in her roles as the sun goddess Amaterasu which Inagaki emphasised. However, the divinisation of female star persona is not unique to the postwar period, as Hara had been the miko (“shrine maiden”) of militarism during the war. This shows the continuity of Hara’s divine persona.[22]

Hara Setsuko was also accused and criticised for Westernisation. She was often called out by the media for the “Western” aspects of her character. Her preference in selecting Western clothing and her appearance, especially her nose that stood out for a common Japanese woman at the time, led to a rumor about Western ancestry.[23]

Conclusion

This project’s examination of the effect of Japan’s defeat in the Second World War has uncovered the influence of Americanisation on the portrayal of female icons in the early postwar period. However, this does not signify that the beginning of Western influence had begun with the U.S. Occupation. The inter-war period from the 1920s to the 1940s also incorporated American culture into Japan. As Japan had previously experienced discomfort from the influences from other nations, the overload of new cultural influences had created a foundation for the eventual desire among the Japanese citizens for the re-emphasis of traditional Japanese values, especially during the Occupation. This desire can be illustrated by the public criticism towards Tanaka Kinuyo for her distinct American influence, for example in her fashion style. In the case of Misora Hibari, her career had begun with sensual performances that benefited from the sexual underground culture of kasutori at the time, which was rooted in the devastation experienced by Japanese citizens after the war. With the rise in demand for representations of traditional values, Misora’s career had shifted during her adulthood as her image in films had drastically changed to highlight the obedience and chastity of women. Demand for innocence and purity were also portrayed in the star persona of Hara Setsuko, an actress known as “eternal virgin,” which is a nickname coming from her continuous roles of unmarried women. Hara’s coherent star persona as a saint-like or virtuous women indicates growth in the market for those innocent, virtuous female characters, which was possibly induced by the rise of more Westernised—thus sexualised in the eyes of men—women after the U.S. Occupation.

[1] Coates 2016, p. 12.

[2] Coates 2016, p. 3.

[3] Coates 2016, p. 42.

[4] Coates 2016, p. 43.

[5] McLelland 2012, p. 3.

[6] McLelland 2012, p. 6.

[7] McLelland 2012, p. 6.

[8] Shamoon 2009, p. 135.

[9] Yamagiwa 1953, p. 14.

[10] Robertson 1988, p. 497.

[11] Sanders 2012, p. 404.

[12] Collins 2011, p.2450.

[13] Collins 2011, p. 2451.

[14] Collins 2011, p. 2454.

[15] Coates 2012, p. 38.

[16] Coates 2012, p. 39.

[17] Shamoon 2009, p. 138.

[18] Shamoon 2009, p. 145.

[19] Kitsnik 2018, p. 39 .

[20] Hansen. 2015, p. 2.

[21] Coates 2016, p. 54.

[22] Coates 2016, p. 55.

[23] Coates 2016, p. 58.

References

Benny, Tong Koon Fung. “A Tale of Two Stars: Understanding the Establishment of Femininity in Enka through Misora Hibari and Fuji Keiko.” Situations: Cultural Studies in the Asian Context 8:1 (2015), 23–44. http://situations.yonsei.ac.kr/product/data/item/1535539292/detail/cf6799f491.pdf.

Coates, Jennifer. “How to Be a Domestic Goddess: Female Film Stars and the Housewife Role in Postwar Japan.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 50 (2016), 29–53. www.jstor.org/stable/26401819.

Coates, Jennifer. Making icons: repetition and the female image in Japanese cinema, 1945–1964. Hong Kong University Press, 2016.

Collins, Sandra. “Sporting Japanese-ness in an Americanised Japan.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 28:17 (2011), 2448–2473.

Hansen, Kelly. “Shifting Gender Roles in Postwar Japan: The On-Screen Life of Actress Hara Setsuko.” Education About Asia 20:2 (2015), 1–5.

Havens, Thomas R. Artist and patron in postwar Japan: dance, music, theater, and the visual arts, 1955-1980. Princeton University Press, 2014 [1982].

Kitsnik, Lauri. “Dancer, Doctor, Maiden, Mother: Tanaka Kinuyo’s Early Star Image.” In Tanaka Kinuyo: Nation, Stardom and Female Subjectivity, ed. Irene González’López and Michael Smith, 36–56. Edinburgh University Press, 2018. www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv7n09rh.8.

McLelland, Mark J. “Sex and Censorship During the Occupation of Japan.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 10:37:6 (2012), 1–22.

Robertson, Jennifer. “Furusato Japan: The Culture and Politics of Nostalgia.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 1:4 (1988), 494–518. www.jstor.org/stable/20006871.

Russell, Catherine. “Three Japanese actresses of the 1950s: modernity, femininity and the performance of everyday life.” CineAction (2003), 34–44.

Sanders, Holly. “Panpan: Streetwalking in Occupied Japan.” Pacific Historical Review 81:3 (2012), 404–431.

Shamoon, Deborah. “Misora Hibari and the Girl Star in Postwar Japanese Cinema.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35:1 (2009), 131–155. DOI: 10.1086/599268.

Yamagiwa, Joseph K. “Fiction in Post-War Japan.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 13:1 (1953), 3–22. www.jstor.org/stable/2942366.

Images:

Daiei Company, Screenshot of Tanaka Kinuyo in the movie “Sorrow is only for women” (Kanashimi wa onna dakeni), 1958. Directed by Kaneto Shindo.

Korpanty, Stephen E. A photograph of Mamoru Shigemitsu, Foreign Minister of Japan, signing the Instrument of Surrender in 1945. Naval History and Heritage Command. https://www.history.navy.mil/photos/images/s200000/s213700c.htm

“Misora Hibari hoshi no nagare ni (uta Misora Hibari)” [Misora Hibari In the flow of the stars (singing Misora Hibari)]. YouTube, uploaded by tikazu higashi, 6 December 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ont4ZePxSsk

Photograph of Tanaka Kinuyo in the movie “A Burden of Life” (Jinsei no onimotsu), 1935. Directed by Gosho Heinosuke.

Shochiku Company. A movie poster of “The Izu Dancer” (Izu no odoriko), 1954. Directed by Nomura Yoshitaro. Ofuna: Shochiku.

Shochiku Company. A screenshot of Misora Hibari in the movie “Sad Whistling” (Kanashiki kuchibue), 1949. Directed by Miyoji Ieki.

Shochiku Company. A movie poster of “Late Spring” (Banshun), 1949. Directed by Ozu Yasujirō.

Shochiku Company. A screenshot of Hara Setsuko in the movie “Late Spring” (Banshun), 1949. Directed by Ozu Yasujirō.

Shochiku Company. A movie poster of Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari), 1953. Directed by Ozu Yasujirō.