By Dong Jiacheng

Introduction

Educating women is an inevitable topic for those who wish to build up a modern education system in their countries. However, it is also one of the most intricate issues in modernization, in which changes in female education would probably alter the status of women and their capacity, as well as ability to make choices, and eventually the whole society. The new state government in early Meiji Japan was facing similar issues. Inspired by the idea of “civilization and enlightenment,” the Meiji government devoted enormous effort into modernizing Japan’s education system. Intellectuals and experts, trained in western-style universities with the latest knowledge about modern technology and ideas, would become the most reliable mediums to sustain the state construction. During the process of modernizing the education system, the newly established state did not forget women. Intending for more women to receive education, the state enlarged the eligibility for female education, and went as far as creating government-funded study-abroad projects in 1871. These efforts by the state produced several prominent women intellectuals, all of great importance for the Meiji state. Some of them were trained abroad, such as Tsuda Umeko and Yamakawa Sutematsu, while others were educated in Japan, such as Miwada Masako and Atomi Kakei. Despite their differing opinions on the social identity of Japanese women, they all contributed to promoting female education in Japan. However, the state would eventually make a choice amongst various options about female education, which favored the state’s interest in economic development as well as maintaining order.

Preface: female education in pre-Meiji Japan

Female education in premodern Japan has held various forms according to the status of women in society. Due to the consistent era of peace and prosperity, the influence of Neo-Confucian philosophies about education, as well as the flourishing of the publication business in Edo period, education for women became a widespread phenomenon in Edo Japan. Parents from different social backgrounds, if samurai or commoners, would willingly spend a substantial amount of money on their daughter’s education as long as they could afford it. Education for samurai and commoner families’ daughters were fundamentally different, but also shared similarities. Samurai households, especially those holding enormous wealth and power, would invite famous scholars as house tutors for their daughters’ education. They would usually begin with basic literacy skills, and then continue learning to read kanbun as well as reciting Japanese and Chinese classics. The most essential component was, however, moral learning on “the Neo-Confucian principles of duty, service and loyalty,”[1] which was also visible in education of their male counterparts. On the contrary, daughters from commoner households would usually be educated in local terakoya or private schools (shijuku), focusing on “popular moral tracts” and “personal satisfaction.”[2] Those who demonstrated exceptional talent in study in their childhood would have the chance to receive literary education that was similar to the one the sons received. However, these two sides of education also shared two things in common. The first is that education towards women was largely based on the assumption of women’s destiny to marry and to easily integrate into her husband’s household. The second is the literature for educating women, which usually included Chinese classics such as Analects and Mencius, Japanese poetry collections such as Hyakunin isshu (One Hundred poems by One Hundred Poets) and Man’yōshū (Ten Thousand Leaves),[3] as well as moral guidance written by Edo Neo-Confucian moralists.

Onna Daigaku

Figure 1: Onna Daigaku, 女大学, 貝原益軒 (双文閣, 1993), title page, National Diet Library.

Among Edo period educational literature, one specific text focusing on moral guidance for women, the Onna daigaku (Greater Learning for Women, 18th Century) assigned to famous Edo moralist Kaibara Ekiken, has drawn many researcher’s attention. Albeit its actual popularity among women during the time remains unknown, it allows us to take a glimpse on one possible form of ethic standard for women in Edo Japan. According to Takaishi, Onna daigaku suggested that a proper woman should achieve her excellences through self-cultivation on essential virtues such as unselfishness, self-sacrifices, “forbearance in place of impetuosity” as well as “complete submission to authority.”[4] In this case, being a proper woman is equivalent to becoming a selfless and subordinate daughter and wife.

Deeply influenced by Confucius and Buddhist ideas, Onna daigaku made the statement on women’s role in society,

…it is a girl’s destiny, on reaching womanhood, to go to new home, and live in submission to her father-in-law, it is even more incumbent upon her than it is on a boy to receive with all reverence her parent’s instructions. Should her parents…allow her to grow up self-willed, she will infallibly show herself capricious in her husband’s house, and thus alienate his affection.[5]

By preconditioning women to believe that their destiny was to become wives, Onna daigaku suggested that women who were poorly educated by their parents would not be capable of performing their duties as wives and would displease their husband’s household. Thus, Onna daigaku argued that moral education for females is essential to society’s harmony, and those qualities that would benefit women are “gentle obedience, chastity, mercy and quietness.”[6] According to the author, women were also responsible for performing various duties in the household, such as taking care of children, serving their husbands’ parents, doing housework, cooking, managing household expenditure, and meanwhile “be on ever on the alert…her own conduct.”[7]

Modernizing education: female intellectuals in early Meiji Japan

Four years after the Meiji restoration, the new government issued the Fundamental Code of Education in 1872, signifying the beginning of the state’s effort in modernizing Japan’s education system. During the process of modernization, women were not left behind. Motivated by Japan’s urgent need for female intellectuals familiar with Western knowledge and ideas, the state sent five female students with the Iwakura Mission to study in the United States in 1872. After finishing their study and returning to Japan, they brought back not only Western knowledge, but also their opinions on female education. In the meantime, several female intellectuals who were educated in Chinese and Japanese classics were also starting to become active in the public field, especially in debates about how women should be educated in a modern sense. Their opinion, whether conservative or progressive, would provide enormous innovation on the self-identity of Meiji Japanese women.

Tsuda Umeko and Shimoda Utako

Umeko was only seven when she was sent to study abroad in the United States with the Iwakura Missions in 1872. Entering Georgetown Collegiate Institute, a private institute for elementary education, Umeko was educated in a regular Western-style fashion, through which she “mastered the English language with an impressive writing style”[8] Besides school knowledge, she also adapted Western religion by being baptized as a Christian in her elementary years. In 1878, Umeko graduated and entered Archer Institute, another private institute for girls mostly coming from upper-class Washington families. There her academic performance was not at all inferior compared to her American counterparts, it was even said that she was in advance of her class.[9] After graduating Umeko was called by the government to return to Japan in 1882. However, despite her profound educational background in Western knowledge, she could hardly find employment in Japan, an environment in which her progressive ideas about female education also found little acceptance. In 1889, Umeko sailed to the United States again to continue her education. She enrolled at Bryn Mawr College to receive higher education, where her academic performance once again impressed the president “who cited her high grades especially in biology and chemistry.”[10] After returning to Japan, Umeko founded Joshi Eigakujuku (Women’s English School)[11] in 1900, which was the predecessor of today’s Tsuda University.

Figure 2: Protrait of Utako Shimoda, ca. 1918.

Figure 2: Protrait of Utako Shimoda, ca. 1918.

Distinct from Umeko’s Western-style education, Utako was educated in a more classical way. Born as Hirao Jizo, a famous kangaku (Chinese learning) scholar’s daughter, Utako was famous for her achievements in the study of kangaku. Based on her knowledge about Chinese classics, Utako was also recognized for her skills in composing waka (Japanese poems of five lines and thirty-one syllables), which was “central to the ‘feminine’ tradition in Japanese aristocratic art,” and “the writing of waka was considered an important part of woman’s education.”[12] Her talent was soon discovered by Ito Hirobumi (1841-1909), who invited her to participate in the construction of modern female education in Japan. In 1885, Kozoku Jogaku, a state-sponsored academy for daughters of aristocracy was founded as a result the of state’s effort, which Utako was made assistant principle, and Umeko was invited to tutor English.[13] From 1893-95, Utako left Japan for a tour to visit female education institutes in Western countries. During her trip to England, she “expressed greatest interest in the role of the wife and mother in affluent Victorian Households.”[14] Returning to Japan following the victory of Sino-Japanese war, Utako founded the Josen Jogakkō (The Women’s Practical Arts School) in 1899,[15] where she intended to implement her philosophies on female education until her death in 1936.

Despite their distinctions in educational background, Umeko and Utako share similarities in their opinions on the importance of female education as an instrument to integrate women into the modern state’s function. Both Utako and Umeko “used nationalism at their authorizing discourse” to advocate “expanded opportunities for women to achieve economic self-sufficiency.”[16] While Utako argued that women should be integrated into state functions “in their roles as wives and mothers,” Umeko, inspired by her experiences in the United States, argued that women ought to be integrated in the social apparatus “as individuals with obligation to service.”[17]

Miwada Masako and Atomi Kakei

Figure 3: Miwada Masako, 国史大図鑑編輯所, 国史大図鑑. 第5巻 (吉川弘文館, 1932-1933), p. 80. National Diet Library.

Figure 3: Miwada Masako, 国史大図鑑編輯所, 国史大図鑑. 第5巻 (吉川弘文館, 1932-1933), p. 80. National Diet Library.

Some other female intellectuals, however, reinforced the essential role of women as “good wives and wise mothers” through emphasizing on Confucian values and Japanese tradition. Miwada Masako and Atomi Kakei are two examples. Born in a Confucian scholar family in Kyoto in 1843, Masako had become familiar with both kangaku and kokugaku (study of Japanese classics) since her childhood. As a talented child, she had started lecturing on classical study since age of twelve. In 1866, she served as a house tutor for Iwakura Tomomi. After the Meiji Restoration, Masako “opened a private academy for Chinese learning in Matsuyama in 1880.”[18] Her effort attracted the prefectural governor’s attention, who invited her to teach in the local teacher training college in 1885.[19] After several years in Tokyo, in 1890 she returned to Kyoto and started teaching at the Prefectural Girl’s Higher School. Two years later she founded the Miwada Girl’s School, a private institution for female education, where she devoted her career into modernizing female education as principle of the school until her death in 1927.

Figure 4: Atomi Kakei, 田島教恵, 淑女鑑 (文永館, 1914), photograph collection, National Diet Library.

Figure 4: Atomi Kakei, 田島教恵, 淑女鑑 (文永館, 1914), photograph collection, National Diet Library.

Kakei’s background was slightly different. Born in a rural elite family in Osaka in 1840, Kakei was a talented student in not only Japanese and Chinese learning, but also Japanese music and painting. In 1866 she followed her family and moved to Kyoto, and in 1870 moved once again to Tokyo, influenced by her father’s decision. Although having years of tutor experience in Osaka and Tokyo already, Kakei “had no special interest in women’s education until her arrival in Tokyo.”[20] In order to realize her expectation about female education, Kakei founded, the Atomi Gakkō, a private institute for female education in Tokyo, which was renamed to Atomi Jogakkō two years later. According to memories of several graduates of the school, Atomi’s girl’s school was “still in a style of a traditional juku”, and teaching was mostly based on moral learnings and preparation for pupils to become “good wife and wise mother.”[21] Kakei served as principle of the institution until her retirement in 1919.

The two female intellectuals have surprisingly similar ideas on the purpose of female education, especially regarding the production of “good wives and wise mothers (ryōsai kenbo)”, which both of them believe to be essential for social harmony as well as state development. Masako, when arguing the importance of “good wives and wise mothers,” made “a distinction between the Western, private ‘home’ and the Japanese ie and katei, the basis of family state.”[22] Kakei, spurred by her unsatisfaction about flippant female students in Tokyo who “did not care about appearing elegant,”[23] claimed that while learning practical knowledge such as English and mathematics, the character education (seishin kyōiku) was “just as important as imparting knowledge.”[24] In summary, both female intellectuals emphasized on mortal cultivation and study of traditional values in order to prepare girls to be compatible with their destined role as “good wives and wise mothers.”

Aoyama Chise and Yamakawa Kikue

Aoyama Chise and Yamakawa Kikue, mother and daughter who lived through two distinct generations of female education in Meiji Japan, found their experience in institutional education drastically different from each other. Chise was born in 1857 in the Mito Domain. As a samurai’s daughter, she received classical education in both Chinese classics and traditional Japanese poetry. Demonstrating her academic talent as a young girl, the intensity of her education was not much different from her male counterparts. Three years after her family moved to Tokyo, Chise enrolled in the Tokyo Joshi Shihan Gakkō (Tokyo Girls’ Normal School) in 1875. The newly founded modern female schools, guided by the idea of “civilization and enlightenment” (bunmei kaika), required students to not only study Western knowledge, but also adapt their lifestyle. Students were “sleeping in Western-style beds, using chairs and tables, and being expected to eat beef along with the rest of ‘enlightened meals’.”[25] Chise graduated in 1879, she married one year later and gave birth to her third child Yamakawa Kikue in 1890.

Figure 5: Protrait of Yamakawa Kikue, 1920.

Figure 5: Protrait of Yamakawa Kikue, 1920.

Kikue’s life story was even more stimulating. Born in late Meiji period, Kikue received a full-fledged modern education since elementary school. However, as a little girl, Kikue found educational content in school “insipid and irrelevant,” in which she became infested with literatures by Fukuzawa Yukichi because his writing “contradicted what was taught in ethics lessons,” and she “read a great deal outside of school, including all the newspapers she could lay her hands on.”[26] Albeit entering a prefectural high school in Tokyo, Kikue’s complaint about the education system did not improve. The curriculums offered by the school consisted of only a few mediocre studies, plus housewife skills and moral learning on becoming “Good wives and wise mothers.” Kikue intensely resented such education and concluded that “the purpose of her teachers and their lessons was to limit and restrict intellects to make students conform to a very ordinary performance.”[27] Later she enrolled in the Tsuda Eigaku Juku, a private institute found by Tsuda Umeko. Even there, Kikue did not find the satisfactory education that she was searching for, since Umeko forbid students from reading literature that were marked by herself as “unsuitable.”[28]

Based on the educational experience of Chise and Kikue from two generations of the Meiji period, it is not hard to detect that the focus of female education shifted conspicuously. What had led to such a drastic change in female education between the two Meiji generation? This question will be further discussed in the next section, which will be an investigation of the Tokyo Joshi Shihan Gakkō, Chise’s alma mater.

Tōkyō Joshi Shihan Gakkō and idea of “Good wives and wise mothers”

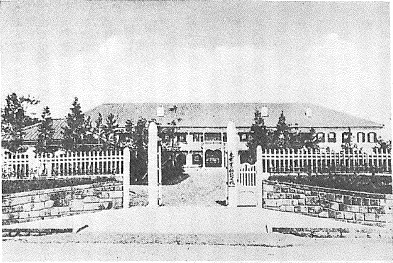

Figure 6: 開校当時の校舎, 1875, Ochanomizu University Digital Archives.

Figure 6: 開校当時の校舎, 1875, Ochanomizu University Digital Archives.

The Tokyo Joshi Shihan Gakkō was founded by the Meiji state in 1875 (Meiji 8) based upon the Ministry of Education’s wish to modernize female education to the extent that “it has no discrimination from that of its male counterparts.”[29] The first entrance examination was held October of the same year, and two months later, seventy-four girls became the first students of the school; Chise was one of them. According to the school’s own publication, the primary goal was “for the purpose of training teachers,” and it also pointed out that “the idea of girl’s school itself was mostly an imported concept…so does the purpose and form of normal school.”[30] Thus, the school at its early stage was fundamentally a replication of its Western models. The curriculums were scheduled in a five-year order, divided into ten grades (from grade 10, the beginning grade, to 1, the final grade). The syllabus for the class of 1875 was as follows:

| Chart 1.1: Syllabus of 1875 | |||||

| Grade 10 | Grade 9 | … | Grade 2 | Grade 1 | |

| Readings |

Geography History |

History Physics |

… |

Economy Natural History Education Theory |

Economy Natural History Education Theory |

| Math | Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division (Four rules) |

Practice with four rules Practice with four rules on decimal point … |

… | Algebra | Geometry |

| Accounting | —— | —— | … | 〇 | 〇 |

| Penmanship | Regular Writing | Regular Writing | … | —— | —— |

| Writing | 〇 | 〇 | … | —— | —— |

| Composition | —— | —— | … | Question and answer composition | Same as last semester |

| Handicraft | 〇 | 〇 | … | 〇 | 〇 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Singing | 〇 | 〇 | … | 〇 | 〇 |

| Gymnastics | 〇 | 〇 | … | 〇 | 〇 |

| Ochanomizu, p. 10-11, Chart I·1*. “〇” indicated that the curriculum was taught, and “——” indicates that it was not. Parts with … were abbreviated. | |||||

It is not difficult to notice from the syllabus that the curriculums were designed to educate female students with basic literacy skills such as writing and composition, modern knowledge such as economy and mathematics, as well as professional training in education theory in order to prepare them for becoming teachers. Guided by the idea of “civilization and enlightenment,” female education was meant to not be inferior from its male counterparts. However, the emphasis on female education shifted drastically in its direction within less than a decade. In 1875, Nakamura Masanao, member of the Meiji Six Society (meirokusha), brought the concept of “Good wives and wise mothers” (ryōsai kenbo). Deeply influenced by the Western idea that wives should be her husband’s “better half,” Nakamura “argued for women’s education so that they could better support their husbands and provide religious and moral instruction for their children.”[31] However, the argument also has another side, which insists that women were ought to become housewives and mothers, and should be prevented from working outside. As Ambros indicated in their article, such belief might have been influenced by Western contemporaries, the “Victorian ideology of womanhood which emphasis ‘purity, piety, domesticity and submissiveness’.”[32] Based on this rather conservative perspective on female education, the focus of the girl’s normal school’s curriculums was shifted to “vocational education and moral learning guided by principles of nationalism.”[33] After several restructures of the curriculum, the syllabus for students of 1887 (Meiji 20) is indicated below.

| Chart 1.2: Syllabus of 1887 | ||||

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |

| Moral Learning | Essentials on humanity and moral | Same as left | Same as left | Same as left |

| Education | General introduction | Principles on intellectual, moral and physical education | School management, teaching method | Educational history, Critics and teaching internship |

| Japanese & Chinese | Grammar, reading and composition | Same as left | General history on literature | —— |

| English | Reading, grammar, translation, composition | Same as left | Same as left | Same as left |

| Math & Accounting | Writing calculation, abacus | Algebra, geometry | Same as left | Single note, compound note |

| Geography & History | Japanese and foreign geography, introduction of cultural-geography | Japanese history | Foreign history | —— |

| Natural History | —— | Phytology, zoology | Minerology, introduction to geology | Physiology and hygienics |

| Physics & Chemistry | —— | Physical theory and laboratory | Physical theory and laboratory, Chemical theory and laboratory | Chemical theory and laboratory |

| Housework | Financial management on clothing, food and living hood, knowledge about management | Introduction on sewing, Practice on sewing different types of cloths, knowledge about management | Same as left | Same as left |

| Penmanship & painting | Regular, normal and cursive writing, improvised drawing | Same as left | Still-life drawing | —— |

| Music | Introduction on names and marks on gamut, solo singing | Introduction on musical instruments, solo singing | Beat method, chorus | Introduction on melody and concord, chorus |

| Gymnastics | Cosmetology, warm-up skill, manual gymnastics | Gymnastics using Dumbbell, cudgel and ball arm | Same as left | Same as left |

| Ochanomizu, p. 37, Chart I·9* | ||||

Compared to the former version made in 1875, the 1887 version of the syllabus provides more organized as well as diverse curriculums for students to prepare them to be educated women and teachers. However, there were two key adjustments that are noteworthy. First, the introduction of economy was removed from the curriculum, replaced by the teaching of “financial management”. Second, moral learning got a greater emphasis within the four-year curriculum plan, which students were required to take throughout their study. The content of moral learning was the delivery of conservative values such as “good wives and wise mothers.”

The conservative approach on female education as well as women’s social role was eventually formalized into laws and civil regulations within a few years. Following the enactment of the Imperial Constitution in 1889, the state issued the Order for the Imperial University, Order for Normal School, Order for Middle School as well as the Order for Elementary School in 1890. Replacing their predecessors, the new orders stated that education must “serve the necessity of state.”[34] The Law on Political Assembly and Association, enacted in the same year, outlawed females from “attending political meetings and forming political parties.”[35] Following the Civil Code of 1898, which limited the head of household exclusively to male lineage, Ambros stated, that “these policies relegated women to the private sphere.”[36]

Conclusion

Although fundamental education for women was not unheard of in Edo Japan, the concept of female education that is distinct from its male counterparts in terms of content, purpose and preference was mostly a Western idea imported during the Meiji period. Female intellectuals in early Meiji Japan who came from diverse educational and social backgrounds like Tsuda Umeko, Miwada Masako and Aoyama Chise, were debating on not only the ideal modality for female education, but also on the proper designation for women’s identity in the new state. Albeit arguing from different perspectives, most of early Meiji female intellectuals agreed that women’s destined position laid in household management, instead of outside activity. The Meiji state, on its way towards building a masculine state, also chose to eventually affiliate with such a conservative approach, shifting the focus of female education from inspiring “civilization and enlightenment” towards cultivating “good wives and wise mothers.” However, the new generation of female intellectuals like Yamakawa Kikue, who were from a more liberate and sophisticated family background, would certainly find such morals repressive and hard to accept.

[1] Tocco 2003, p. 211.

[2] Tocco 2003, p. 212.

[3] Tocco 2003, pp. 205, 208.

[4] Kaibara and Takaishi 1905, p.11.

[5] Kaibara and Takaishi 1905, p.33.

[6] Takashi 2000, p.34.

[7] Takashi 2000, p.40.

[8] Duke 2009, p.105.

[9] Duke 2009, p.106.

[10] Duke 2009, p. 111.

[11] Howe 1993/93, p. 103.

[12] Johnson 2013, p. 68.

[13] Johnson 2013, p. 70.

[14] Johnson 2013, p. 72.

[15] Johnson 2013, pp. 74-45.

[16] Johnson 2013, p. 67.

[17] Johnson 2013, p. 86.

[18] Mehl 2001, p. 581.

[19] Mehl 2001, p. 582.

[20] Mehl 2001, p. 588.

[21] Mehl 2001, pp. 589-590.

[22] Mehl 2001, p. 597.

[23] Mehl 2001, p. 588.

[24] Mehl 2001, p. 590.

[25] Tsurumi 2000, p. 8.

[26] Tsurumi 2000, p. 10.

[27] Tsurumi 2000, p. 12.

[28] Tsurumi 2000, p. 14.

[29] Trans. From Japanese: “Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku Hyakunen-shi” Kankō Iinkai 1985, p. 3.

[30] Trans. From Japanese: “Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku Hyakunen-shi” Kankō Iinkai 1985, p. 8.

[31] Ambros 2015, p. 118.

[32] Ambros 2015, p. 119.

[33] Trans. From Japanese: “Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku Hyakunen-shi” Kankō Iinkai 1985, p. 17.

[34] Trans. From Japanese: “Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku Hyakunen-shi” Kankō Iinkai 1985, p. 35.

[35] Ambros 2015, p. 117.

[36] Ambros 2015, p. 117.

References

Ambros, Babara R. “Imperial Japan: Good Wives and Wise Mothers.” In Women in Japanese Religions, 115-133. NYU Press, 2015.

Duke, Benjamin. “The Modern Education of Japanese Girls: GEORGETOWN, BRYN MAWR, VASSAR, 1872.” In The History of Modern Japanese Education, Constructing the National School System, 1872-1890, 97-111. Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Howe, Sondra Wieland. “Women Music Educators in Japan during the Meiji Period.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 119 (1993/94), 101-109.

Johnson, Linda L. “Meiji Women’s Educators as Public Intellectuals: Shimoda Utako and Tsuda Umeko”. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 44 (2013), 67-92.

Kaibara Ekiken and Takaishi Shingoro. Women and wisdom of Japan. London: The Orient Press, 1905.

Mehl, Margaret. “Women educators and the confucian tradition in Meiji Japan (1868–1912): Miwada Masako and Atomi Kakei.” Women’s History Review 10:4 (2001), 579-602.

Takashi Kato. “Edo in the seventeenth century: aspects of urban development in a segregated society.” Urban History 27:2 (2000), 189-210.

Tocco, Martha C. “Norms and Texts for Women’s Education in Tokugawa Japan.” In Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern China, Korea, and Japan, ed. Dorothy Ko, JaHyun Kim Haboush and Joan Piggott, 193-218. University of California Press, 2003.

Tocco, Martha. “Made in Japan: Meiji Women’s Education.” In Gendering Modern Japanese History, ed. Barbara Molony, Kathleen Uno, 39-60. London: Harvard University Asia Center, 2005.

Tsurumi, Patricia E. “The State, Education, and Two Generations of Women in Meiji Japan, 1868-1912.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 18 (2000), 3-26.

“Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku Hyakunen-shi” Kankō Iinkai 「お茶の水女子大学百年史」刊行委員会. Ochanomizu joshi daigaku hyakunen-shi お茶の水女子大学百年史, Ochanomizu Joshi Daigaku, 1985.

Further recommended reading

al‐Khaizaran, Huda Yoshida. “The emergence of private universities and new social formations in Meiji Japan, 1868–1912.” History of Education 40:2 (2010), 157-178.

Anderson, Emily. “Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Development of the Feminist Movement (review).” Monumenta Nipponica 66:2 (2011), 352-355.

Anderson, Marnie S. “Women and Political Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Case of the Okayama Joshi.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 44 (2013), 43-66.

Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya. “Shōfujin (Little Women): Recreating Jo for the Girls of Meiji Japan.” Japanese Studies 30:2 (2010), 247-262.

Lukminaite, Simona. “Developments in Female Education of Meiji Japan: As Seen from Jogaku Zasshi’s Editorials by Iwamoto Yoshiharu.” PhD dissertation, Dimitrie Cantemir Christian University, 2015.

Lukminaite, Simona. “Women’s Education at Meiji Jogakkō and Martial Arts” Asian Studies 6:2 (2018), 173-188.

Molony, Barbara. “A Place in Public: Women’s Rights in Meiji Japan by Marnie S. Anderson, and: Reforming Japan: The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in the Meiji Period by Elizabeth Dorn Lublin, and: Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Development of the Feminist Movement by Mara Patessio (review).” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 73:1 (2013), 194-203.

Nagai Michio. “Westernization and Japanization: The Early Meiji Transformation of Education.” In Tradition and Modernization in Japanese Culture, ed. Donald H. Shively, 35-76. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Patessio, Mara. “Women getting a ‘university’ education in Meiji Japan: discourses, realities, and individual lives.” Japan Forum 25 (2013), 556-581.

Saito Rika. “Constructing and Gendering Women’s Speech: Integrated Language Policy through School Textbooks in Meiji Japan.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal 30/31 (2006), 132-159.

Stanley, Amy. “Enlightenment Geisha: The Sex Trade, Education, and Feminine Ideals in Early Meiji Japan.” The Journal of Asian Studies 72:3 (2013), 539-562.

Wright, Diana E. “Female Crime and State Punishment in Early Modern Japan.” Journal of Women’s History 16:3 (2004), 10-29.

Yonemoto, Marcia. “Written Texts-Visual Texts: Woodblock-Printed Media in Early Mordern Japan (review).” Monumenta Nipponica 61:1 (2006), 107-112.

Motoyama Yukihiko. Proliferating Talent: Essays on Politics, Thought, and Education in the Meiji Era. University of Hawai’i Press, 1997.