Charles A. Robinson’s Rescues

By Theodore Shaw

Abstract: After the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, the US and other Allied nations came to Japan to accept the surrender and commence the Occupation of Japan. After the surrender ceremony, a group of three Jesuit Navy Chaplains serving on US Navy warships in Tokyo Bay, Charles A. Robinson, Paul L. O’Connor and Samuel H. Ray, made a daring trip from the newly claimed US Navy Base at Yokosuka to Sophia University in Tokyo to determine the fate of the Jesuits living and working at the university. The visit has joined the lore of Sophia University and is a prominent event in its documented history. This project will demonstrate that Robinson actually had a much deeper role in the life of Sophia University and also a critical role in freeing the first prisoners of war from the many POW camps in Japan.

Keywords: Jesuits, Navy Chaplains, Sophia University, World War II, USS Missouri, Surrender of Japan, Great Kanto Earthquake, Charles A. Robinson, Paul L. O’Connor, Samuel H. Ray

Introduction

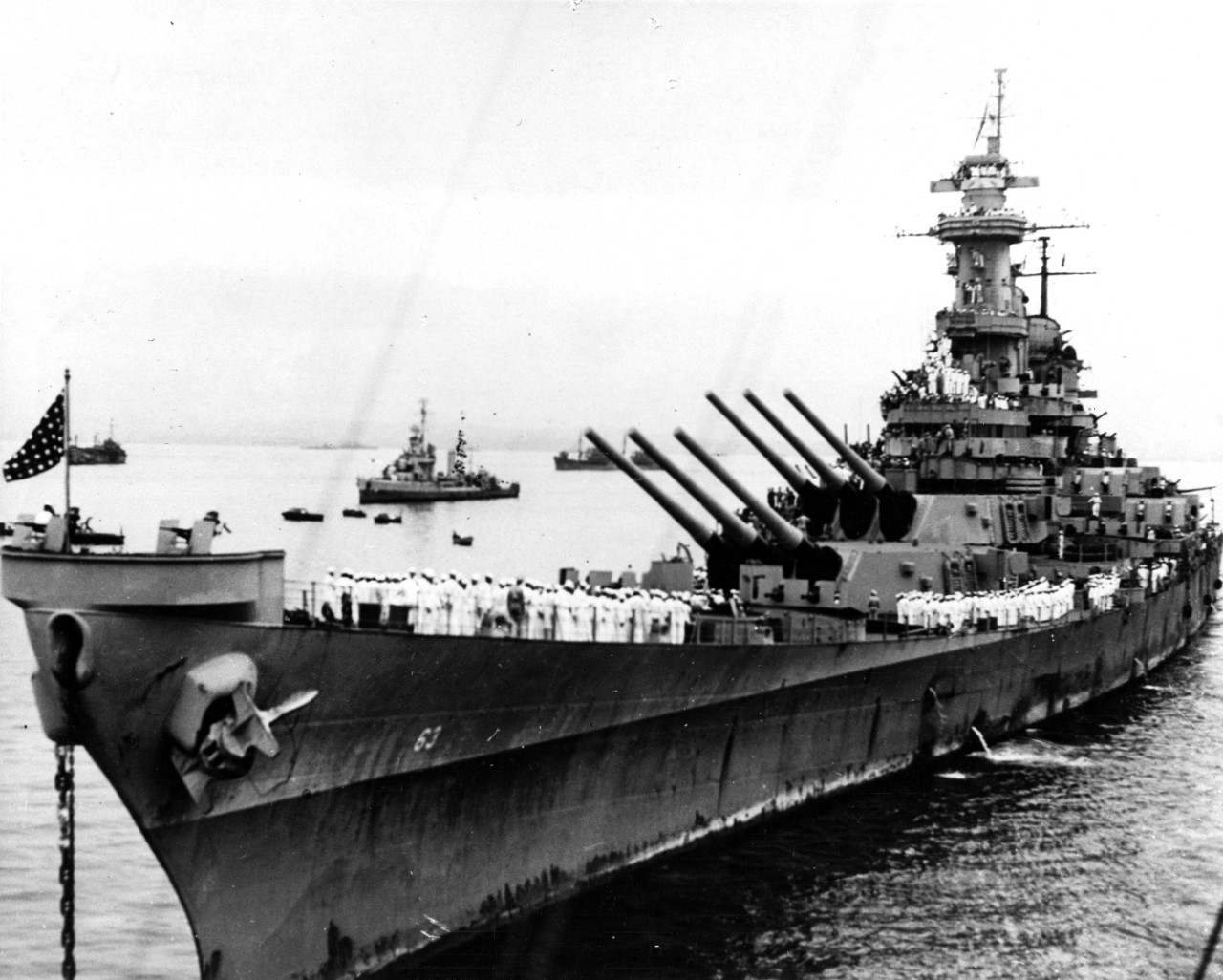

Sophia University in Tokyo was the first Catholic university certified to operate in Japan.[1] One of the more memorable events in its 100-plus year history happened right after Japan surrendered at the end of World War II, when three Navy Jesuit chaplains visited the campus to provide emergency assistance and determine the fate of the faculty. This visit happened on 5 September 1945 and was led by a former faculty member, Charles Robinson, Society of Jesus (S.J.) (1896–1988), who had taught at Sophia during the 1920s. Robinson, the chaplain on the Battleship USS Missouri (BB63)[2], was accompanied by his relief, Paul O’Connor, S.J. (1909–1974), and Samuel Ray, S.J. (1894–1983), chaplain on the Seaplane Tender USS Hamlin (AV15).[3] While the Japanese had already surrendered, the Allied military forces had not yet moved troops into Tokyo, meaning that they would be making it without military protection, a potentially risky venture. They were not stopped by either of the Allied Occupation forces or Japanese officials, and Robinson still remembered the campus location, so they arrived without incident. They found the Jesuits at Sophia malnourished but alive. The campus and surrounding areas had been hit during the bombing raids, leaving severe damage to a couple of the campus buildings and the surrounding area a wasteland. The Jesuit churches in Japan and the Jesuits staffing them were in mostly similar straits. The food and clothing that the team brought helped alleviate the faculty’s suffering from malnutrition. They also provided the first chance in years to inform the Jesuits outside Japan, via letters written by two of the chaplains and another from Bruno Bitter (1898–1988), a prominent Jesuit at Sophia, of the status of the Japan mission. The letters were mailed from USS Missouri and addressed to Zacheus Maher, S.J. (1882–1963), the American assistant to the Superior General during World War II.[4] They informed him of the status of the church in Japan and expressed a strong desire for more Jesuits to expand their ability to carry on the mission.[5]

While this trip verified that the faculty members had survived the privations of the war without serious injury or imprisonment, it was not the first time Robinson had participated in disaster relief activities for Sophia University or in Japan. His tour of duty as a teacher at Sophia in the 1920s began soon after the Great Kanto Earthquake on 1 September 1923.[6] Then, decades later, he was involved in liberating the first prisoners of war from the camps in Japan at the end of World War II.[7] This project will provide the background of Robinson’s three rescues, using the word rescue in the broad meaning that he supported emergency relief and recovery activities following a disaster or war. Although the ongoing COVID-19 crisis limited the research that could be conducted for this project, the number of sources discovered, including Jesuit and US and Allied military sources, provides a sufficiently comprehensive story that goes beyond what has been collated to date into a single document.

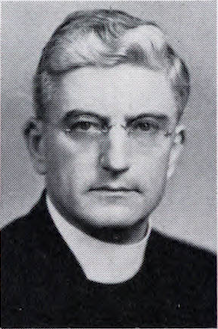

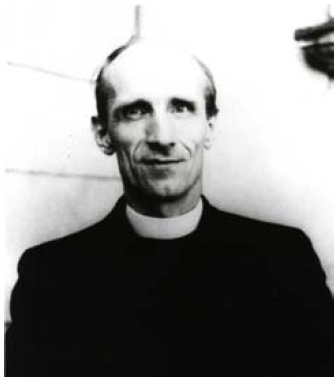

Who was Charles Robinson, S.J.?

Charles Aloysius Robinson was born of parents from Northern Ireland in Brooklyn, NY, on 17 April 1896. From the earliest age, he exhibited an amazing ability to memorize facts, which helped him quickly learn foreign languages.[8] He went to Regis College in Denver,[9] completing the high school diploma requirements in 1912.[10] He then entered the Society of Jesus as a member of the Naples Province on 29 July 1912 at St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant, Missouri. He completed his novitiate and juniorate St. Stanislaus in 1916, then proceeded to Mount St. Michaels in Hillyard, Washington, to complete the philosophate.[11] He received his A.B. from Gonzaga University (in Spokane, Washington) in 1918, followed by his M.A. in Psychology and Philosophy on 19 June 1919, also from Gonzaga.[12] Soon afterward, he became a member of the newly created Missouri Province. He completed work at the Immaculate Conception Seminary in Montreal and was ordained on 29 June 1922. His next assignment following his ordination was at the Ignatius College at Valkenburg, Holland, for a year of theology. It is after his return from Holland to the US that the essay continues below.

One potentially formative event happened while he was at Mount St. Michaels. The Spanish Flu hit the community at Hillyard, Washington, in November 1918. Around 80 members fell ill, with over half of them confined to bed. There is no record whether Robinson got sick, but at a minimum, he would have witnessed the results of a pandemic.

Robinson’s First Rescue

On Saturday, 1 September 1923, roughly two minutes before noon, Tokyo and its surrounding regions were struck by a massive earthquake with a magnitude of over seven. It was a disaster that came to be known as the Great Kanto Earthquake. Mark J. McNeal, S.J. (1874–1934), one of the Jesuits then teaching at Sophia, maintained a record of what he experienced and witnessed, here is a portion.

1st – At 11:53:44 this morning, towards the close of our noon examinations, I felt the strongest earthquake shock I had ever experienced. I went out and saw that our Academic Building was a wreck and learned that the water mains were broken and saw fires starting up all over town. I baptized conditionally an old lady who had been struck by a falling house…All electricity and gas were stopped. Many refugees from fire or earthquake camped for the night in our garden.

2nd – I went with Fr. [Father] Keel to the American Embassy, which was wiped out, and to the Swiss Embassy, and learned that rail and wireless connections were broken. To the Church of the Sacred Heart and learned from the pastor that three Catholic churches in Tokyo were destroyed…Fire raged all day and all night and came to within two blocks of our place a little after midnight and then turned back…

4th – Fr. Eylenbosch returned from Shizuoka; walked all night from Yokohama; said no city existed there anymore; streets full of corpses…

October 3rd-A notable shock during the night brought down a big piece of our tower which had remained standing after the great earthquake…

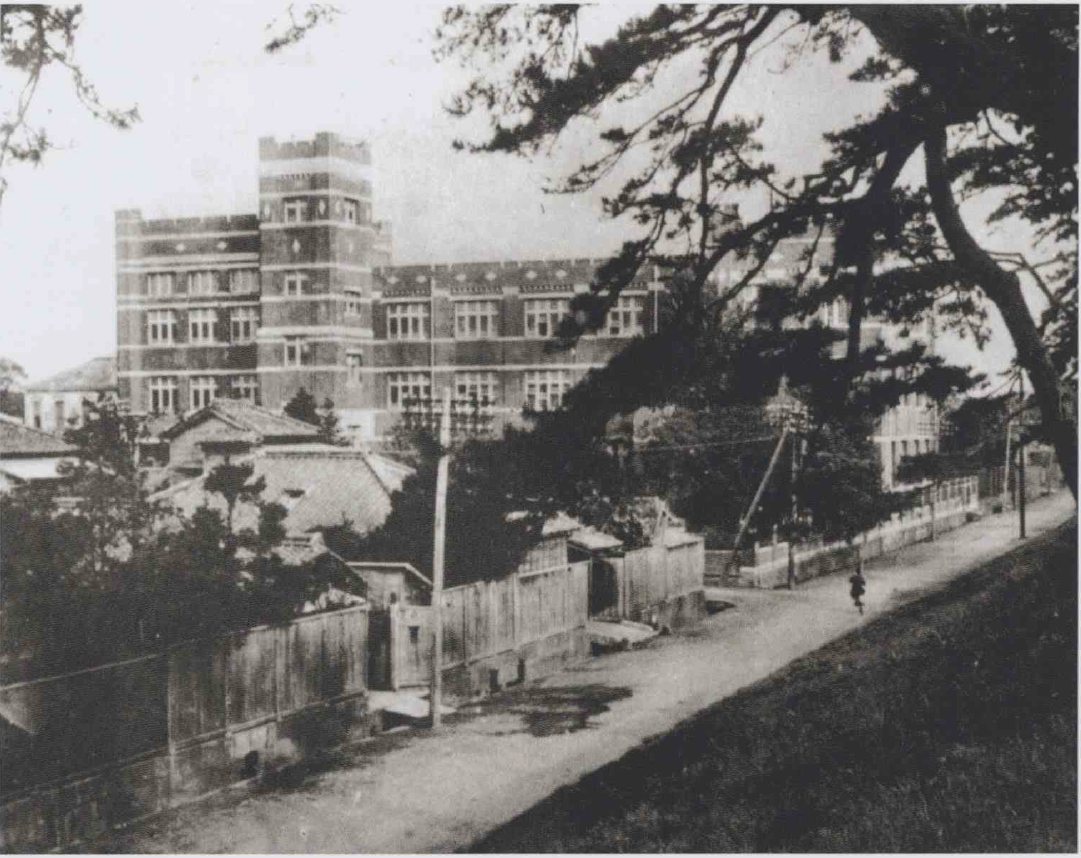

What We Had – Three and a half acres of terra firma in the heart of a city of about 3,000,000 inhabitants; two Japanese dormitory buildings, an old western style residence used for offices, chapel and library; a three-story brick academic building containing twelve large classrooms, two large halls, a students’ library and offices, erected in 1914 for $60,000; a reinforced concrete faculty building, finished June, 1923, for about $50,000 and capable of accommodating a faculty of twenty members.

What We Have – Three and a half acres of terra infirma in the heart of a desert in which 75,000 people are camping out, 500 are unsheltered and the rest sharing quarters with their friends. The academic building is all gone except the first floor, and that is full of cracks. The faculty building has cracks in every wall, big holes around the foundation and leaks everywhere. The library and chapel building has plaster down and chimney broken. One Japanese dormitory building is full of refugees, the other is being used for classrooms, which are unheated and badly lighted.[13]

The damage to the tower is apparent from these two photos of the Red Brick Building. The scope of the death and destruction brought about by the earthquake was unparalleled in Tokyo’s history up to that point.

Robinson was in Denver when the earthquake happened. Having been ordained on 29 June 1922, he had just completed his last year of theology studies at Valkenburg, Holland. Along with expanding his knowledge of theology, he had learned German there, which he would need for his upcoming transfer to Sophia University in Tokyo and its German-administered faculty. No orders or other paperwork listing his planned transfer date have been found. However, a notice was published on 1 September 1923 (the date of the earthquake) in the Japanese Catholic periodical Katorikku Taimusu, stating that Robinson would be coming to Sophia to teach commerce.[14] It is therefore assumed that he was slated to go to Sophia, and, after he heard the news about the earthquake, he either contacted or was instructed by his superiors to go to Tokyo immediately and assist the Jesuits there with recovery efforts. He was able to respond quickly, and a week or so later he was embarked on the first ship out of Seattle headed for Tokyo, the President Jackson, bringing emergency supplies with him. The ship arrived at Yokohama, Japan, on Sunday, 23 September. He was met by someone named Mr. Jillard of Nippon Electric Company (no known connection to Sophia University or the Catholic Church), who drove him to Sophia’s campus in Tokyo.[15] As had been previously planned, Robinson stayed on for the 1924/25 school year as a member of the Sophia faculty, teaching English, Economics, and Accounting. He continued teaching English there for the next two academic years. He remained on the faculty at Sophia for the 1927/28 school year,[16] but he spent it at St. Louis University, and also visited Hot Springs, North Carolina, to accomplish his tertianship.[17] After this, he transferred to Marquette University for the 1928/29 school year to teach Philosophy & Religion.

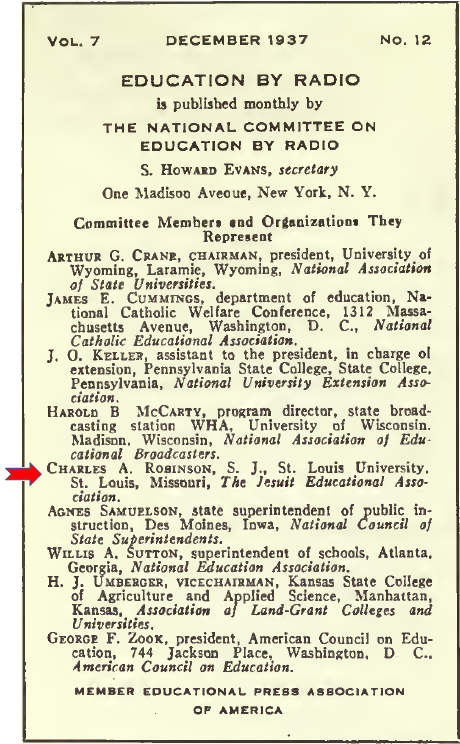

His Prewar Years in America

His year of teaching at Marquette was followed by a transfer to St. Louis University for what would become his longest teaching position, lasting from 1929 to 1943.[18] He taught Philosophy and Psychology. In 1931, he received his Ph.D. in Philosophy from Gregorian University in Rome. In addition to teaching, he served as the Jesuit representative to the National Committee on Education by Radio from 1930 to the early 1940s, pursuing the use of radio for education and spreading Jesuit teaching.[19] St. Louis University was one of the earliest schools to establish a radio station and began broadcasting the first regular religious radio program,[20] so he was at the ideal school to help develop the policies that would guide the use of this still mostly untapped resource. While his efforts to improve education continued into the 1940s, America could not continue to remain apart from the war taking place on both ends of the Eurasian continent.

His Next Rescue

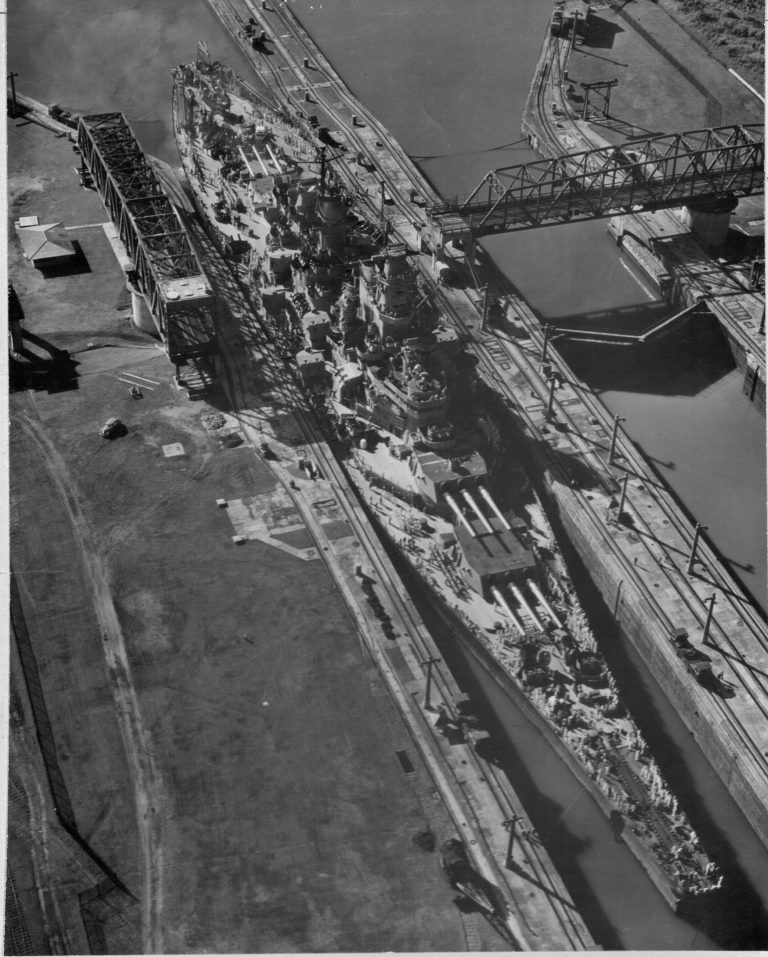

The US finally became embroiled in World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. As was the case with so many American men during those years, Robinson left what he was doing to join the war effort. He joined the Navy, getting his commission in September 1943 and joining the roughly 60 Jesuits who served during that war as chaplains in the US Navy.[21] He was assigned to the Pacific Theater through the end of the war. His first Navy assignments at the beginning of 1944 were at shore stations in Oahu, Hawaii, at the Naval Hospital at Aiea Heights and Naval Air Station at Ford Island. He then departed Hawaii in February 1945 for the Battleship USS Missouri (BB63), the last of the Iowa-class battleships to be commissioned by the US Navy.[22]

On “Mighty Mo” Robinson served as the Ship’s Chaplain under the Senior Chaplain, Methodist Commander Roland W. Faulk (1907–1995). He remained the Ship’s Chaplain until he was relieved by another Jesuit, Paul L. O’Connor (1909–1974), near the end of August 1945.[23] From this point on, he was assigned duties that leveraged his unique knowledge and experience, becoming part of a group of three Navy chaplains who were the first to go ashore in Japan after the war.[24]

Following the loss of Okinawa in June 1945, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August, and the declaration of war by the Soviet Union, Japan capitulated on 14 August. The cessation of hostilities was announced the next day at noon by a recording of the Emperor broadcast by radio to all Japanese people in Japan and military forces overseas, which brought the fighting to an end. A group of Japanese government representatives was sent to the Philippines to coordinate the surrender met with Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964) and his staff. His staff instructed them regarding the measures to implement in preparation for the occupation, including disarming their military forces in Japan. At this meeting, MacArthur’s staff indicated that they wanted the occupation force’s main body to arrive in Japan on 25 August. However, this ended up being delayed by five days due to requests from the Japanese Government for more time to complete pre-arrival demobilization and a typhoon that passed through on 26 August.

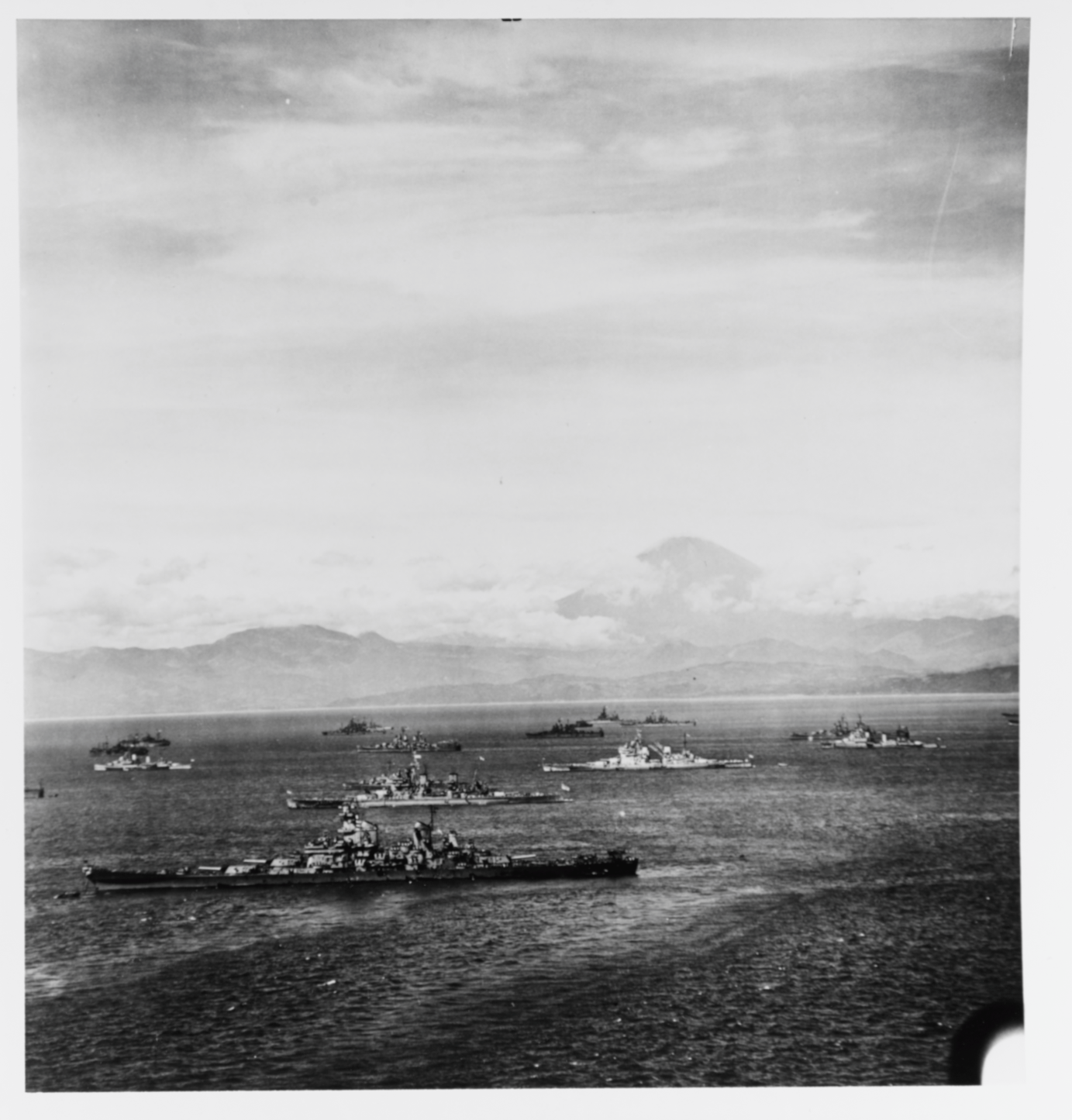

The first Allied Navy ships began arriving at Sagami Bay outside Tokyo Bay, on 27 August.

The advanced party of the American ground forces landed at Atsugi Airbase, south of Tokyo, on 28 August, while the fleet elements of the occupying force entered Tokyo Bay on the 29th. Having faced increasing numbers of suicide attacks by Japanese military forces in 1945, Allied military personnel weren’t sure they could trust that the Japanese had truly surrendered. Although the Allies were concerned about acts of revenge upon their arrival, they found the Japanese military forces had carried through on their agreement to demobilize their weapons and other defensive systems. Allied ships and landing forces enjoyed a peaceful arrival in Tokyo Bay.[25]

While the Japanese had cooperated in demobilizing their military forces in Japan, they still had a large number of Allied and other prisoners of war (POW) scattered in camps throughout Japan. The US estimated that there were 36,000 POWs in Japan, with 8,000 of them being Americans. Throughout the countries that Japan had conquered during the war, they had mistreated many of their POWs.[26] For this reason, the Allied commanders focused on quickly securing the safety of the surviving POWs in Japan. Following Japan’s surrender, Allied air forces focused some of their intelligence-gathering efforts on locating the POW camps and providing emergency rations pending the occupation forces’ arrival.[27] The dire situation of the POWs was emphasized for Allied naval commanders the day they arrived in Sagami Bay by a fortuitous rendezvous with Private E.D. Campbell of the British Royal Army Service Corps, and J.W. Wynn of the British Royal Marines. The TG 30.6 report describes how seriously their information was received:

There had been a fresh reminder of the ferocity and brutality with which the Japanese had waged war. On the evening of 27 August, two British prisoners of war hailed one of the Third Fleet’s picket boats in Tokyo Bay and were taken on board the San Juan, command ship of a specially constituted Allied Prisoner of War Rescue Group. Their harrowing tales of life in the prison camps and of the extremely poor physical condition of many of the prisoners prompted Halsey [Third Fleet Commander, Admiral William Halsey (1882–1959)] to order the rescue group to stand by for action on short notice.[28]

Their description of the appalling situation at the POW camps and precarious physical condition of many of the POWs reinforced the need to expedite the rescue efforts.[29]

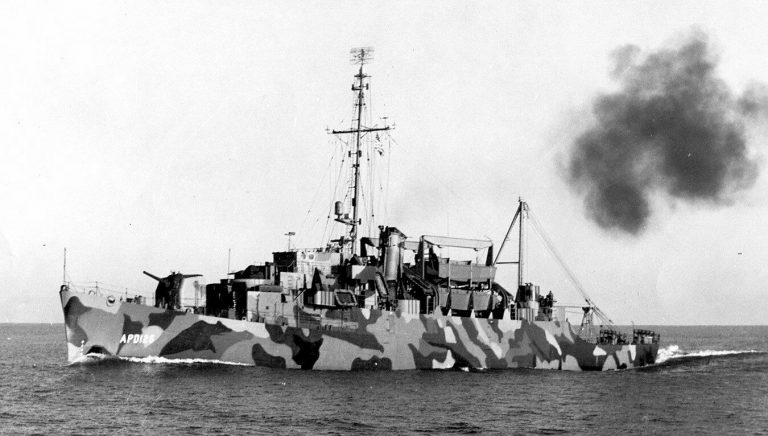

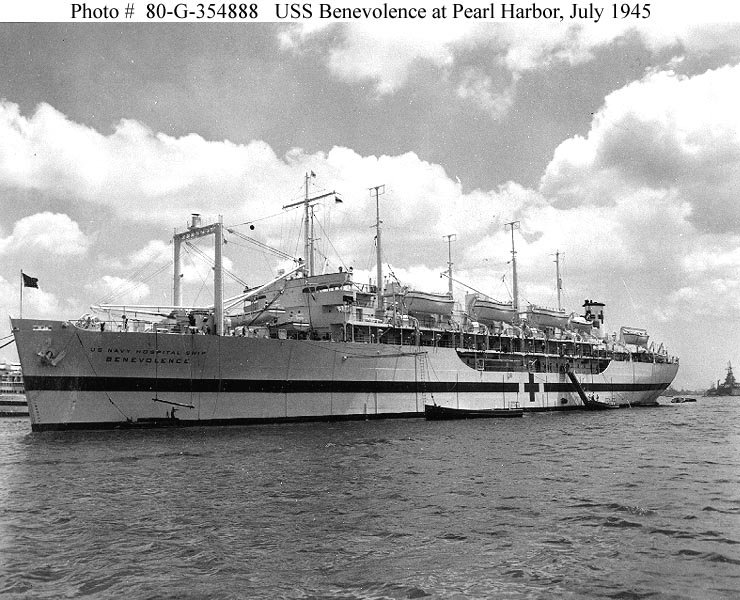

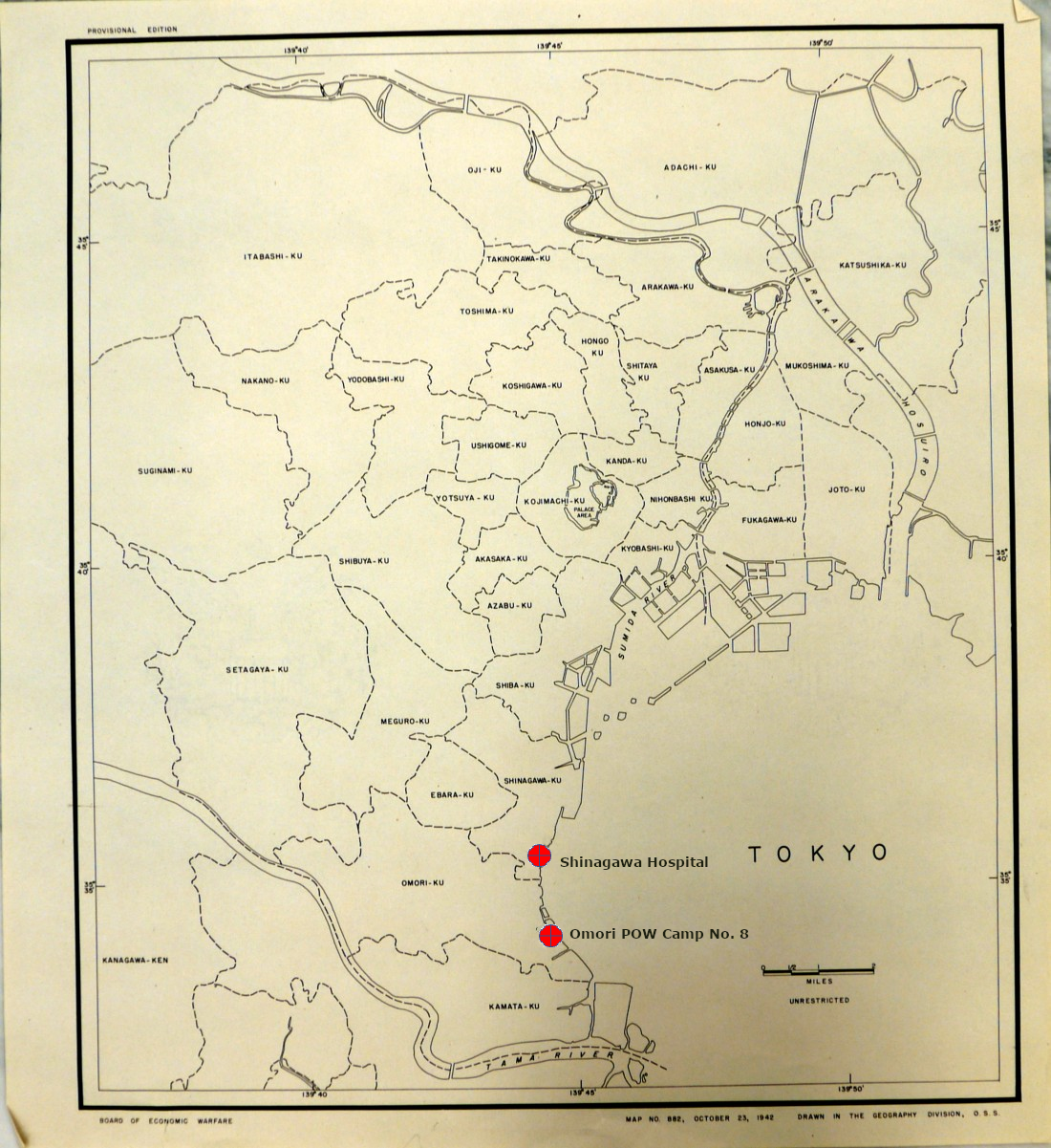

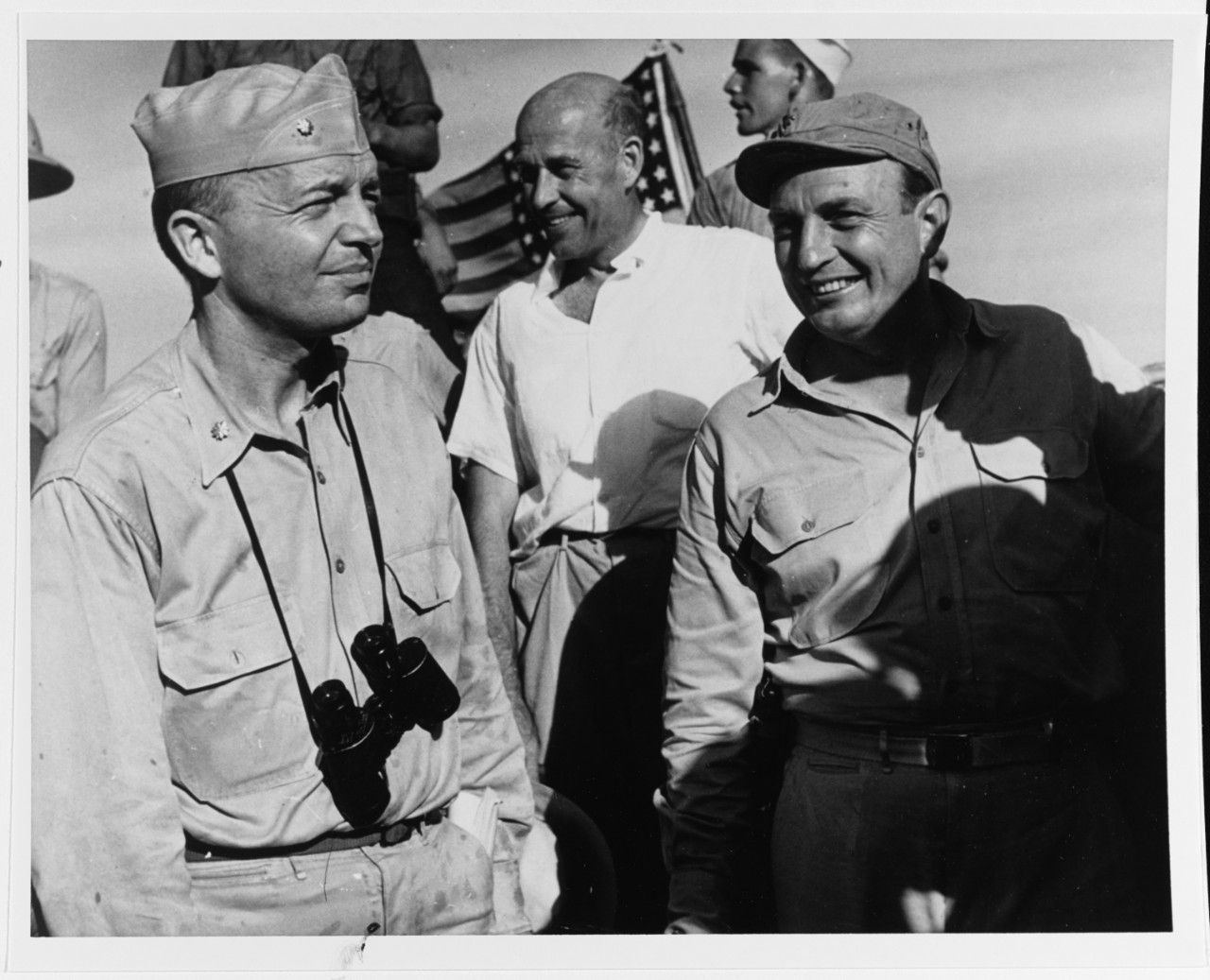

The Commander of Task Group Thirty Point Six (TG 30.6), Commodore Rodger W. Simpson (1898–1964), had been tasked by Halsey to plan and execute the evacuation and medical support of POWs in Third Fleet’s area of responsibility. This area equated to the coastal area of roughly the northeastern half of Honshu. Embarked on the Light Cruiser USS San Juan (CL54), Commodore Simpson commenced preparations for this mission on the day of Japan’s surrender. MacArthur had already directed Eighth Army to prepare a plan for the rescue of POWs in Japan, but the information provided by the British POWs provided sufficient rationale to expedite rescue operations while Eighth Army forces were still flowing into Japan. The harrowing conditions at the POW camps convinced US Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Chester Nimitz (1885–1966) to approve immediate commencement of rescue operations by naval forces following his arrival on the morning of 29 August. Upon entry into Tokyo Bay on the 29th, several Third Fleet ships were assigned to TG 30.6, including the High-Speed Transport Ships USS Gosselin (APD126) and USS Reeves (APD52); Destroyer USS Lansdowne (DD486); and amphibious landing craft from Amphibious Force Flagships USS Teton (AGC14) and USS Ancon (AGC4). The Hospital Ship USS Benevolence (AH13) and aircraft launched from the Light Aircraft Carrier USS Cowpens (CVL25) were also tasked to support the TG 30.6 rescue efforts. This group would expand significantly in subsequent days.[30]

While the forces that would execute the rescue and evacuation of POWs had spent time preparing for their mission, the rescue parties would also need interpreters to ensure that they could communicate effectively with the Japanese military guarding the POW camps. O’Connor had relieved him as the Ship’s Chaplain for USS Missouri. Having become fluent in Japanese while teaching at Sophia University from 1923 to 1926, he was assigned to TG 30.6 to assist Commodore Simpson with the rescue effort. The lack of interpreters available upon arrival Tokyo was a significant concern for Commodore Simpson, as documented in the Operation Plan “Spring-Em,” promulgated on 27 August. The landing party’s description included the following requirement: “Interpreters – when and if available.”[31] Robinson was embarked on USS Missouri, the flagship for Admiral Halsey, so all it took was a request from Commodore Simpson to his superior in command to satisfy his requirement for an interpreter. Robinson supported the first few days of rescue efforts.[32]

During the afternoon of 29 August, TG 30.6 transited to Northern Tokyo Bay. They anchored a few miles east of the Omori POW Camp Number 8, which intelligence had determined to be the headquarters for all POW camps in Tokyo. Landing craft from the task group ships were sent to begin recovery operations. Prisoners in the camp could see the craft heading their way, and they were ecstatic. A few of them even jumped in the water to escape the camp before the craft arrived.[33] In the words of one of them, Sergeant Frank Fujita, US Army,

I was so excited and so emotional that I just could not wait for the boats to get to us, so I jumped into the bay to swim out to meet them. Two or three others jumped in also and we started swimming out towards the on-coming PT boats, which turned out to be landing craft…The next thing I knew, two large hands had me by the head and were pulling me out of the water, and then another sailor helped lay me on the deck of the landing craft…As the boats pulled into the Omori docks, the whole camp was crowded at the little island’s edge, and from somewhere American, British and Dutch flags appeared and were being wildly waved.[34]

One would understand the elation of the POWs by learning one fact regarding the experience of the unit in which Sgt. Fujita served. Almost one-half of his unit of almost 550 soldiers did not survive captivity in Japan’s POW camps.[35]

While the prisoners were euphoric, the Japanese guards had a different idea. The description of events by Sgt. Fujita continues.

All the POWs in camp were whooping and yelling as the landing party came ashore and was met by our camp C.O. They no sooner had shaken hands when the Japanese camp commander and his staff came through the camp and walked up to the commodore and demanded to know what he was doing here and stated, “The war is not over yet!” The commodore told him that the war was over for him and that he was removing all the POWs from Omori immediately, and what was more, he had better be damn sure that all Allied POWs in the Tokyo area were at this very spot tomorrow morning because he was taking them out also.[36]

The TG 30.6 report of the encounter notes that “the task unit was there to evacuate the men to the hospital ship and that their cooperation was required.”[37] Having a competent interpreter like Robinson present, who could communicate the US intent to the camp commander in appropriately diplomatic Japanese, would have been essential to securing their cooperation and understanding the rationale for expediting the release of POWs from all the camps.

The evacuation of the Omori camp proceeded into the night. The senior POW, Commander Maher, former gunnery officer on the light cruiser USS Houston (CA30) that had been sunk in the Battle of Sunda Strait in 1942,[38] assembled the POWs for guidance from TG 30.6. A radio was set up at the camp to communicate with the San Juan. Evacuation of the POWs in the worst condition was the priority, so they started with the “18 litter cases” and continued with the “approximately 125 ambulatory cases.”[39] The USS Reeves reports the events as follows:

Anchored off Tokyo Harbor at 1715 in company with TG 30.6, LCVP’s [a type of amphibious landing craft] engaged in bringing out released POW’s to U.S.S. Benevolence (AH13) from Tokyo camps. Went alongside Benevolence at 2130 to receive ambulatory repatriates aboard. Received 149 repatriates aboard from Benevolence, first group of POW’s to be liberated from Tokyo area. Underway from alongside at 0010 and anchored in company with TG 30.6 at 0040. Remainder of day spent bringing out released POW’s from Tokyo camps with LCVP’s.[40]

Sgt. Fujita was one of the last out of the camp.

The really sick and bad off were taken aboard the landing craft first and taken to a hospital ship out in the bay. Then we others were taken, first come, first serve. Capt. Ince, Smitty and I…got on board just after midnight on the morning of 30 August 1945. We were taken to a big white ship that had a big red cross painted on the sides. It was the hospital ship SS Benevolence.[41]

While TG 30.6 rescued POWs at Omori Camp Number 8, they were told of a worse camp nearby, called the Shinagawa Hospital. Robinson was sent with the search party to locate and assess conditions at the hospital. Here is how he describes this mission.

I went in the first boat that left to seek the hospital camp at Shinagawa, which was 2 or 3 miles closer toward the center of the city. There were no electric lights working in that area, and we had no planes to help us. But with the aid of our own flashlights from the boat we managed to get there. The misery of this so called hospital camp was frightful. Most of the men had to be carried about 200 yards to the boats. About 2100, the chaplain of the USS San Juan came ashore here and reported to me for work. He was Fr. M. F. Forst. Everyone worked well until about 0400, Thursday, 30 August, when I inspected every barracks with my flash to see that we were not missing anybody. Then I returned in the last boat to the first camp at Omori, to check that camp, and returned with Commander Stassen to the USS San Juan about 0530.[42]

TG 30.6 reported that this “evacuation was completed at daybreak, a total of 707 POW was freed.”[43]

Following the rescue operations at Omori and Shinagawa that continued into the morning of 30 August, TG 30.6 continued rescuing prisoners that day at other waterfront camps. TG 30.6 described the efforts on the 30th as follows:

Information of additional camps was obtained during the night from the prisoners of war so that at dawn the landing craft were divided into two units, one of which proceeded to evacuate Kawasaki Camp number one, the Kawasaki Bunsho Camp and Tokyo sub camp number 3 in the adjoining area. The other unit proceeded to the Sumidagawa Camp deep in the Tokyo inner channels and evacuated the prisoners of war from that camp.[44]

For Robinson, there would be no rest, since following his 0530 return to USS San Juan, “I said Mass immediately with Fr. Forst’s assistance, and then left again about 0630 as navigator to find Kawasaki. We found it without mishap, and emptied three more camps in the vicinity that day.”[45] TG 30.6 noted that “The transfer of these prisoners of war to the Benevolence was completed at 2130 on 30 August, bringing the total to 1,496 who had been freed.”[46]

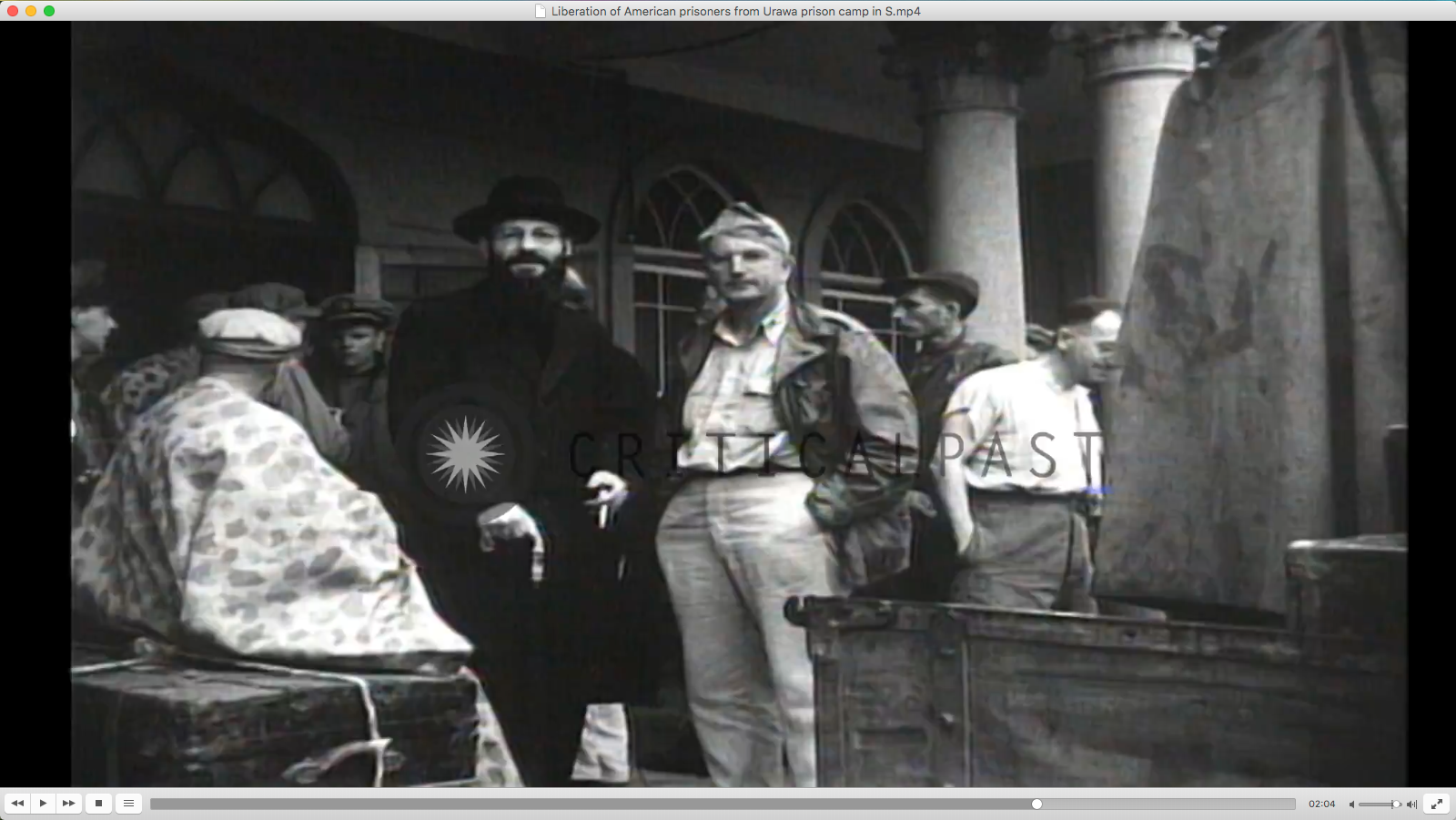

According to Robinson’s report, Saturday the 31st was another busy day, taking the rescue efforts to camps further north. “On Saturday, 31 August, civilian photographers and newspapermen were allowed to go ashore. Until that day, the Navy had not allowed them to accompany us. That day we worked north of Tokyo getting out women and men internees. Some of these had known me 20 years previously.”[47]

On the same day, TG 30.6 was contacted by a representative to the Eighth Army to participate in a joint conference and bilaterally plan their rescue efforts. This meeting was held on 1 September. As the lead command for recovery of POWs, the Eighth Army took charge of the remainder of the rescue efforts in the Tokyo area. TG 30.6 would provide ships and other Navy assets to support recovery efforts as required by the Eighth Army. TG 30.6 would head to different locations to conduct rescue operations, starting at Hamamatsu and Nagoya.[48] There is no record of Robinson’s activities following the initial phase of POW rescue operations, other than being onboard USS Missouri during the Japanese surrender ceremony on 2 September. At some point, he returned to his role as interpreter for Commander Task Force 31, Admiral Oscar Badger (1890–1958).[49] Additionally, he must have been concerned for the people that he had worked with in Tokyo twenty years before. But before anything else, the surrender ceremony on 2 September onboard USS Missouri would take center stage, with Robinson and the rest of the crew angling for a good view.

Robinson Accomplishes Another Rescue in Support of Sophia University

Having supported the exhausting effort to free the first of the POWs at the camps in and around the Tokyo and Kanagawa areas, Robinson had to have been thinking about the Jesuits with whom he taught for three years in the 1920s. He likely heard about the bombing from the people he had just rescued from Urawa and may have inquired about his old worksite. He must have been worried about the campus’s condition and how his old faculty mates had weathered the storm of the war years.

By the beginning of September 1945, the Eighth Army had assumed responsibility for directing and carrying out the POW rescue operations throughout Japan. The Navy was now in a supporting role and USS Missouri was preparing to depart Japan on 6 September. Knowing that he would be leaving Japan soon, Robinson was able to gather some supplies and get two other Jesuits, his relief on USS Missouri, O’Connor, and the chaplain on the USS Hamlin, Ray, to accompany him on a daring trip to Yotsuya in Tokyo.[50] A letter written by O’Connor captures the atmosphere of the trip.

On Wednesday 5 Sept., Fr. S. H. Ray of the New Orleans Province, now attached to the USS Hamlin, Fr. Charles Robinson, whom I relieved on board this ship and attached at that time as interpreter for Admiral Badger’s staff, and myself got hold of a jeep from the Yokasuka [sic] Naval Base and made our way into Tokyo to visit our men at the University there. We had doubts about our ability to complete the trip as the military had only gone as far as Yokahama [sic] and reportedly were guarding the entrances to Tokyo and excluding all personnel. But the fathers at the University must have been praying for our appearance, for though stopped a number of times, we managed to bring in our load of food and clothing.[51]

Today we cannot know how Robinson connived his way past these checkpoints. Having participated in operations rescuing POWs, he likely used a similar rationale for his trip to Yotsuya.

From a few perspectives, this was a mission that only Robinson could carry out. Along with having been to several locations around Tokyo and Kawasaki in the previous few days to free POWs, he was fluent in Japanese, and he had learned his way around Tokyo and its environs when he taught at Sophia in the 1920s. Without Robinson’s experience and persistence, this trip would not have been successful. Indeed, O’Connor’s letter later notes that they “made it only because Fr. Robinson knows the language. There may be some Jesuits in the army of occupation to help them out. But so far none have shown up, as we were the first ones to reach them.”[52] The occupying forces had just begun to arrive in Japan, there were numerous POW camps to be liberated, and the big cities had been devastated. Support for a Catholic University in Tokyo in early September 1945 would not have been a priority for the other military authorities, but it was for Robinson.

Upon arrival at the campus, they found a situation that both concerned and relieved them. O’Connor’s letter continued:

And very welcome we were, too. None of the Jesuits had starved to death or been killed, but all of them were suffering from malnutrition, subsisting especially during the past few months on soy beans, rice, and some few scraps of meat that occasionally they were able to get. We could stay only a few hours as we had to make the long trip back to the ships and be aboard before night fall, but the following is some information I was able to gather from the Fathers in Tokyo… In the University of Tokyo, the old building was completely destroyed by an incendiary bomb, but luckily the Fathers were able to stop the fire from doing much damage to the main building adjacent to it, though two classrooms are fire blackened and a corner of the roof slightly burned. This loss they look upon as providential, for a month later another incendiary bomb ignited houses to the rear of the University and a gale swept the fire through the entire district. Because of the fire break presented by the old demolished building the main building was saved. So the building now stands in the center of a completely burned out section.[53]

The damage to the campus was severe, but they had saved the newest building from severe damage and preserved some of the library’s contents. However, the area immediately surrounding the campus was flattened.

The visit allowed them to learn the destruction that had been visited upon the other Catholic churches throughout Japan. As described by O’Connor:

Personal injuries from the bombings were slight…Throughout the mission our churches at the following stations were destroyed; Okayama, Kure, Fukuyama, Hiroshima. All together, 80 Catholic places, (schools, convents, churches) were burned out in the whole of Japan. Enemy aliens were interned, but the German, Japanese and Swiss priests were allowed to continue work. During the past year the German Jesuits, according to their reports, were under constant surveillance and heckling by the Japanese Government… The situation right now of the Jesuits in Tokyo is not an enviable one. (And they report that the Jesuits in the country districts have suffered more from lack of food than they have.) The food we gave them will last them for about a week. We have notified the Red Cross but I doubt if that organization can do much for them, so many people in Tokyo have not even a roof over their heads.[54]

The physical toll upon the Catholic mission in Japan paralleled the damage suffered in all the big cities nationwide. Yet this was not the worst thing they would learn about the destruction meted out to Japan.

They were also to hear a first-hand account of the devastation that resulted from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Fr. Lasalle, superior at Nagatsuka and, if I am not mistaken, the superior of the entire mission, received cuts and bruises from the atomic bomb at Hiroshima only 8 kilometres [equivalent to approximately 5 miles] from the Novitiate at Nagatsuka. Fr. Schiffer, ordained last year, and at the time of the bombing stationed at Nagatsuka where the philosophate and theologate have been located for the sake of safety, was cut by glass splinters. He was present in Tokyo when we arrived and described the effect of the atomic bomb as first a blinding flash, as of magnesium fire, then a terrific and awesome pressure from above that blew out all windows and scattered furniture as in a doll’s house shaken by hand, then silence absolute and complete for about eight seconds, and finally the rumble and roar of houses collapsing in the city. He says that as far as he can figure out the bomb itself made absolutely no noise, but admits that the noise may have been lost in the roar of buildings toppling. Our buildings were not greatly damaged by it, aside from windows and furniture and a weakening of some walls. The fathers made their way into town and gave what help they could, which was not much, for the entire city was wiped out. Some of the living casualties were taken to the novitiate and treated, but all those burned by the bomb later died, even though, as happened to one man, only one finger was burned.[55]

The destruction described here makes the survival of everyone at his facility more miraculous.

For all of the damage at all of the Catholic facilities, the spirits of the Jesuits on that day was a sign of their continued devotion to their mission. O’Connor’s letter continued,

when we asked them what we could do for them their first request was not for food but for manpower. They wanted, if it were at all possible, American scholastics to teach English and to wield influence among the intellectual group in the country who are going to rebuild Japan. They fear greatly an influx of Protestantism, because since the war the Japanese people admire secretly American efficiency, and this they associate with Protestantism. The German Jesuits also greatly fear that they will not be allowed to remain in Japan. So they need man power and, as one of them put it, “to whom should we look but to America.” This primary request of theirs was all the more appealing because they did not ask first for food and I saw how hungry they were, so hungry in fact, that, though we had brought some K rations for our own lunch along with the boxes of food for them, we ended up by slipping the K rations in with the boxes and refusing their touching invitation to lunch. Their first request was for their missionary work.[56]

The German Jesuits recognized their tenuous status as citizens of a former enemy nation, so they hoped that American Jesuits could carry on the mission to convert Japanese into Catholicism.

The visit to Sophia’s campus allowed the Navy Jesuits to leave that day knowing that the Catholic mission in Japan and its priests had survived the war. Along with the information they learned, they also carried a letter from Fr. Bitter, a German Jesuit with significant influence in European circles. Not having been able to communicate outside of Japan since early in the war, he entrusted a letter to the visitors to be mailed from the ship and inform his superiors of the conditions in Japan. Robinson and O’Connor returned that day to USS Missouri,[57] to depart the next day just after 5 a.m. on a voyage that would carry them to Guam, Pearl Harbor, the Panama Canal, and finally to Norfolk, VA, arriving there on 18 October 1945. The day after arriving, Robinson detached from the USS Missouri.[58] He would spend the rest of his time on active duty in a temporary duty status at Camp Peary, VA. While at Camp Peary, he went on terminal leave before he was released from active duty on 12 February 1946.[59]

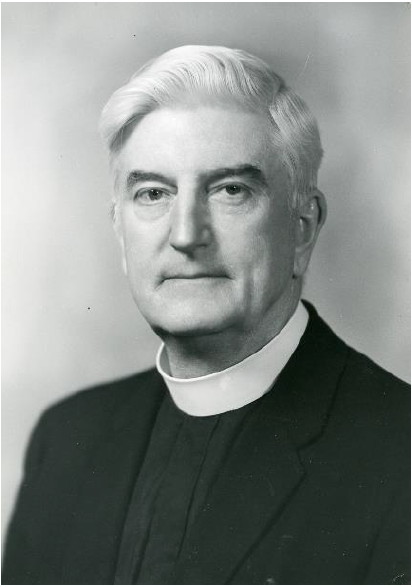

The ten days that Robinson spent in Japan in 1945 must have influenced him regarding what to do after he was released from his commitment to the Navy. As for the other members of the trio, O’Connor remained onboard USS Missouri as the Ship’s Chaplain into 1946.[60] He did not continue his service in the Navy much longer, though, as he was released from active duty on 16 June 1946.[61] His postwar Jesuit career saw him advance to the President of Xavier University, before passing away on 10 September 1974.[62] The third team member, Ray, ended up spending much more of 1945 in the Tokyo area, and he carried out a promise he had made on 5 September.

Support for Sophia Continued by the Remaining Team Member

Following the departure of Chaplains Robinson and O’Connor onboard USS Missouri on 6 September, Ray continued to be assigned to USS Hamlin, which remained in Tokyo Bay. He had promised on the 5th “to try to bring more food in a couple of days.”[63] However, not knowing Japanese or directions to campus meant that it would be complicated to pull off. Even though he was pessimistic about the likelihood of success, he would make an attempt.

Before trying to return to Sophia’s campus, he went on trips to Yokohama and Tokyo that allowed him to meet other church representatives, such as Archibishop Spellman (1889–1967) of New York, along with visits to the American and British Consulates and the International Red Cross. 20 September was the date he chose to undertake his next visit to Sophia. His recounting of this story will sound familiar to any tourist who ever visited Japan:

On Thursday the 20th I went by boat to Yokohama, fifteen miles distant, carrying sugar, soap and candy for the Jesuits in Tokyo. In Yokohama near the dock I boarded a trolley for the railroad station and took the train to Tokyo. This was a bit venturesome since I did not know the way and just asked as I went along. At Tokyo I got off and began asking for Yotsuya. Finally, after contradictory directions, a Japanese took me downstairs and up to another platform whence trains departed for Yotsuya. As I rode along on this electric train, the only American in the car, and surrounded by a crowd of Japanese, it suddenly occurred to me that they could slit my throat and throw me into a ditch. But we had been assured that the Japanese would not harm us under the present conditions. I got off at the seventh stop, Yotsuya, went up the stairs and walked two blocks to Sophia, the Jesuit university. I met the Fathers there and had many questions to ask.[64]

While he had questions to ask, he had a much more extensive visit than the first one to get answers.

He remained overnight in Tokyo, followed by a full day of activity.

The next day began with Mass in the domestic chapel at the altar of the Japanese Martyrs at 0600…Returning to the ship that evening with Commander McKeel and Commander Connor, we took Fr. Roggendorf back for an overnight stay on our ship. He ate dinner with the captain that night and saw steak, white bread, butter, and ice cream for the first time in years. The men on the ship plied him with questions about Japan and the Japanese.[65]

This was the last known contact that Ray had with the Fathers at Sophia. While USS Hamlin remained in the Tokyo area, his relief arrived on Thanksgiving Day, 22 November 1945. The next day, Ray transferred to a cargo ship, the USS Muliphen (AKA-61), and on the 24th departed Tokyo Bay. As he relates the voyage: “We made the great circle in fifteen days through rough seas and high winds that blew off the ice fields of Alaska.” Knowing he was returning home, he had one wish: “I was determined to be home by Christmas, reached Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on December 19th, 1945, and said Mass at midnight at home on Christmas.”[66] He was the last of the three Jesuits to return to the US, he was released from active duty on 9 February 1946.[67] His postwar career as a Jesuit carried him to becoming a Dean at Loyola University, New Orleans, before passing away on 22 November 1983.[68]

Robinson Returns to Sophia One More Time

Robinson’s missionary zeal wasn’t extinguished by his brief visit to Sophia in September 1945. After his release from Navy duty in February 1946, he wasted little time in the US before returning to Japan. A published report described it thus:

Father Charles Robinson of the Missouri Province is back in Tokyo. Before the war he was a professor in the Catholic University there. As a naval chaplain, he was detached from the battleship Missouri to act as interpreter with the first force that went ashore to liberate Allied prisoners of war. After his return to America, he had hardly finished his terminal leave before he was off again for Japan, this time as a missionary.[69]

Following his return to Japan, he rejoined the faculty of Sophia, teaching English until his departure in 1951. His obituary notes that he also served as a liaison officer for the occupying Allied Forces during this tenure at Sophia, although no additional information has been discovered regarding this.[70]

After his tenure at Sophia was completed, he returned to St. Louis University for another stint, remaining there until 1958. After that, his teaching career came to an end as he took up residence at the Holy Trinity Parish in Trinidad, Colorado. He remained in Trinidad for the remaining 30-years of his life. A more complete accounting of his life may have to wait until 2038, when his Jesuit personnel record can be accessed by researchers.

Endnotes

[1] “History of Sophia University,” Sophia University, accessed 24 July 2020, https://www.sophia.ac.jp/eng/aboutsophia/history/history/index.html

[2] “BB” denotes that the USS Missouri is a battleship. Other ship types that will appear in this essay include “AV” for Seaplane Tender, “CL” for Light Cruiser, “APD” for High-Speed Transport Ship, “DD” for Destroyer, “AGC” for Amphibious Force Flagship, “AH” for Hospital Ship, and “CVL” for Light Aircraft Carrier.

[3] “The Battleship Missouri and Sophia University,” Sophia 100th Anniversary, No. 14, Sophia University.

[4] McCoog, With Eyes and Ears Open: The Role of Visitors in the Society of Jesus, 18.

[5] O’Connor, Bitter and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323-328.

[6] Jōchi Daigaku, Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集, Vol. 2 (1913–1928), 68.

[7] Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 325-482.

[8] Fisher, “In Appreciation. Fr. Charles A. Robinson, S.J.,” 26.

[9] This happened before Regis College split into a high school and college, later university.

[10] Many details regarding Fr. Robinson’s Jesuit career and other details were kindly provided by Otsuka Sachie of the Sophia University Archives, David Wessels of the St. Miki Library at Sophia University, Ann Knake of the Jesuit Archives & Research Center, David Kingma of the University Archives & Special Collections for Gonzaga University, and Anne Ryckbost of the Xavier University Library.

[11] Readers unfamiliar with the process of becoming a Jesuit should refer to the James Martin article “Novice? Regent? Scholastic? A guide to Jesuit formation (and lingo)” at the link in the bibliography.

[12] Gonzaga University served as the accredited degree-granting entity for Mount St. Michaels. The A.B. is equivalent to a university Bachelor of Arts (B.A.).

[13] “Varia.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LIII, 1 October 1924: 110-116.

[14] Jōchi Daigaku, Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集, Vol. 2 (1913–1928), 167.

[15] Jōchi Daigaku, Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集, Vol. 2 (1913–1928), 68.

[16] Jōchi Daigaku, Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集, Vol. 2 (1913–1928), 42-45.

[17] Fisher, “In Appreciation. Fr. Charles A. Robinson, S.J.,” 26.

[18] Navy Department, United States Navy Chaplains 1778-1945: Biographical and Service-Record Sketches of 3,353 Chaplains, Including 2 Who Served in the Continental Navy, 237.

[19] National Committee on Education by Radio, “A Report of Stewardship,” 55-62.

[20] Federal Radio Education Committee, “Saint Louis U. to Short Wave Its Program to South America.”

[21] The total is arrived at by tallying all of Navy Jesuit chaplains in World War II listed in Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 339-346.

[22] Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 414.

[23] US Navy, USS Missouri: Logbook, August 1945.

[24] US Navy, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, 270.

[25] Takemae Eiji, The Allied Occupation of Japan, 46-57.

[26] MacKenzie, “The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II,” 512-518; Reynolds, RL30606: U.S. Prisoners of War and Civilian American Citizens Captured and Interned by Japan in World War II. The Issue of Compensation by Japan.

[27] Official documents, photos, and details of the prisoner of war recovery efforts were kindly made available by the Center for Research, Allied POWS Under the Japanese 日本軍政下の連合軍捕虜 研究センター.

US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[28] Shaw, The United States Marines in the Occupation of Japan, 6.

[29] US Navy. USS San Juan: War Diary for August 1945. 7 September 1945.

[30] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945; US Navy. USS San Juan: War Diary for August 1945. 7 September 1945; Henry Shaw, The United States Marines in the Occupation of Japan (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1969), 6.

[31] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[32] US Navy, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, NAVPERS 15808, edited by Clifford M. Drury (1950), 270.

[33] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[34] Fujita, Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun, 313-315.

[35] Fujita, Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun, ix.

[36] Fujita, Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun, 315.

[37] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[38] Naval History and Heritage Command, “The Last Battle of USS Houston: Sunda Strait, 28 February–1 March 1942,” accessed 18 July 2020.

[39] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[40] US Navy. USS Reeves: War Diary for 13-31 August 1945. 31 August 1945.

[41] Fujita, Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun, 315-316.

[42] US Navy, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, 270.

[43] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[44] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[45] US Navy, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, 270.

[46] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[47] US Navy, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, 270.

[48] US Navy. Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six: Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945, 22 September 1945.

[49] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 328.

[50] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 328. In an article published 15 years after the war, Ray notes that two others had accompanied the three Jesuits to Sophia U. on 5 September: Methodist Chaplain Lawrence L. Lacour of USS Piedmont, and Warrant Officer Pat Young of USS Hamlin. They aren’t mentioned by the other two members of the group or anyone at Sophia, nor do they appear in the photos taken on the day of the visit; see Ray, “Chaplain and Victory in the Pacific,” 123.

[51] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323.

[52] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 325.

[53] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323-324.

[54] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323-324.

[55] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323-324.

[56] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 325-326.

[57] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 323-328.

[58] US Navy, USS Missouri: Logbook, August through November 1945.

[59] Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 414.

[60] US Navy, USS Missouri: Logbook, December 1945.

[61] Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 409.

[62] Xavier University Library. “Paul L. O’Connor portrait.” Xavier University Presidents Photographs, Exhibit: A Showcase of Scholarship, Creativity and Preservation. Accessed 22 July 2020.

[63] O’Connor, Bitter, and Robinson, “Letters from Tokyo,” 325.

[64] Ray, “Chaplain and Victory in the Pacific,” 124.

[65] Ray, “Chaplain and Victory in the Pacific,” 125.

[66] Ray, “Chaplain and Victory in the Pacific,” 127.

[67] Giblin, “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960,” 412.

[68] “Obituaries,” Alexandria Daily Town Talk, Saturday, 26 November 1983, page A-5.

[69] “Varia,” Woodstock Letters, Volume LXXV, 1 October 1946: 270.

[70] Fisher, “In Appreciation. Fr. Charles A. Robinson, S.J.,” 26.

References

American Catholic Historical Society. “ABOUT CHAPLAINS: Compiled from various Catholic newspapers and lay publications.” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Vol. 58, No. 2 (June, 1947): 132, 153, 165. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40175966

“Announcements.” Pacific Stars and Stripes. 6 November 1950. Page 2. Accessed 14 Jun 2020. https://starsandstripes.newspaperarchive.com/pacific-stars-and-stripes/1950-11-06/page-2/robinson?ndt=ex&pd=6&py=1950&pm=11

Center for Research, “Allied POWS Under the Japanese 日本軍政下の連合軍捕虜 研究センター.” Accessed 22 June 2020. http://www.mansell.com/pow-index.html

Cressman, Robert J. The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Naval Historical Center, 1999.

Federal Radio Education Committee. “Saint Louis U. to Short Wave Its Program to South America.” FREC Service Bulletin, October 1941. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=uJEoJ5XVuGIC&pg=PP102&lpg=PP102&dq=FREC+Service+Bulletin+%22charles+a.+robinson%22&source=bl&ots=QMI9-i8pHF&sig=ACfU3U3KKMtH3dC5il_RxK79A-TM2TbSqw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj08Ov79MDqAhXD-GEKHcbpCKUQ6AEwAHoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=FREC%20Service%20Bulletin%20%22charles%20a.%20robinson%22&f=false

Fisher, Joseph P., S.J. “In Appreciation. Fr. Charles A. Robinson, S.J. April 17, 1896-April 22, 1988.” Missouri Province Newsletter, Oct. 1988: 26.

Frank, Benis M. and Henry I Shaw, Jr. Victory and Occupation: History of U. S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Volume V. Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1968. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=wuxmAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA484&lpg=PA484&dq=%22allied+prisoner+of+war+rescue+group%22&source=bl&ots=oXjlWpV0Nj&sig=ACfU3U2Q3hJvi9ICU6O1KNiPj92nHWvNkQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiD35fLqJPqAhViKqYKHaHHAFIQ6AEwAHoECAYQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22allied%20prisoner%20of%20war%20rescue%20group%22&f=false

Fujita, Frank. Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun: The Secret Prison Diary of Frank ‘Foo’ Fujita. Denton, TX: University of North Texas, 1993.

Fukubayashi, Toru, n.d. “POW Camps in Japan Proper.” POW Research Network Japan. Accessed 2 June 2020. http://www.powresearch.jp/en/archive/camplist/index.html

Giblin, Gerard F., S.J. “Jesuits as Chaplains in the Armed Forces 1917-1960.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LXXXIX, Number 4, 1 November 1960: 325-482. https://jesuitonlinelibrary.bc.edu/?a=d&d=wlet19601101-01

Gonzaga University. Catalogue 1918–1919 and Bulletin 1919–1920. Spokane, WA: Spokane University, 1919. https://cdm16011.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/api/collection/p15486coll9/id/2361/page/0/inline/p15486coll9_2361_0

Jōchi Daigaku. Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集. Vol. 2 (1913–1928). Ed. Klaus Luhmer. Jōchi Daigaku, 1989. https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/repository/view/repository/00000035386

Jōchi Daigaku. Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集. Vol. 3 (1928–1948). Ed. Klaus Luhmer. Jōchi Daigaku, 1989. https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/repository/view/repository/00000035387

Jōchi Daigaku. Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集. Vol. 4 (1948–1969). Ed. Klaus Luhmer. Jōchi Daigaku, 1989. https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/repository/view/repository/00000035389

Jōchi Daigaku. Jōchi Daigaku shishiryōshū 上智大学史資料集. Suppl. (1903–1969). Ed. Klaus Luhmer. Jōchi Daigaku, 1989. https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/repository/view/repository/00000035391

MacKenzie, S.P. “The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II.” In The Journal of Modern History, Sep. 1994, Vol. 66, No. 3 (Sep. 1994), pp. 487-520.

Martin, James. “Novice? Regent? Scholastic? A guide to Jesuit formation (and lingo).” America, the Jesuit Review. Accessed 26 July 2020. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2013/08/11/novice-regent-scholastic-guide-jesuit-formation-and-lingo

McCoog, Thomas M (ed.). With Eyes and Ears Open: The Role of Visitors in the Society of Jesus. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2019.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. Victory in the Pacific, 1945: Volume XIV of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960.

National Committee on Education by Radio. “New Program for NCER.” In Education by Radio, Vol. VI, Nos. 1-2, January-February 1936: 1. https://archive.org/details/educationbyradio04natirich/page/n7/mode/2up

National Committee on Education by Radio. “A Report of Stewardship.” In Education by Radio, Vol. 7, No. 12, December 1937: 55-62. https://archive.org/details/educationbyradio04natirich/page/n7/mode/2up

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Allied prisoners of war cheering their rescuers, as the U.S. Navy arrives at the Omori prison camp, near Yokohama, Japan, on 29 August 1945.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-490000/80-G-490444.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Allied Prisoner of War Camp, Omori, Japan, 1945.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-pacific/japanese-surrender/allied-prisoners-of-war/80-g-490459.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Allied prisoners of war , freed from Japanese camps in the Tokyo area, are brought in small harbor craft to USS Benevolence (AH-13).” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-pacific/japanese-surrender/allied-prisoners-of-war/80-g-490461.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Allied Ships Present in Tokyo Bay During the Surrender Ceremony, 2 September 1945.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/allied-ships-present-in-tokyo-bay.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “American and Japanese officers confer at Omori Allied Prisoner of War Camp, August 29, 1945, as prisoners are rescued by US Navy mercy parties, operating in the Tokyo and Yokohama areas.” Accessed 22 Jun 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-pacific/japanese-surrender/allied-prisoners-of-war/80-g-490459.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Benevolence (AH-13).” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/benevolence-i.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Commander Harold E. Stassen, USNR (left), Flag Secretary to Commander, Third Fleet, Admiral William F. Halsey Accompanies Commodore Rodger W. Simpson, USN, Commander, Task Group 30.6 (right) , as they head for shore on a mission to rescue Allied prisoners of war at the Aomori camp near Yokohama, Japan, circa 29-30 August 1945.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-people/s/stassen-harold-e/80-g-700864.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Commodore Rodger W. Simpson, USN Chaplain Charles Robinson, USN.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/numerical-list-of-images/nara-series/80-g/80-G-470000/80-G-473723.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Gosselin (APD-126).” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/g/gosselin.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Lansdowne (DD-486).” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/lansdowne.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “The Last Battle of USS Houston: Sunda Strait, 28 February–1 March 1942.” Accessed 18 July 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1942/java-sunda/last-battle.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “San Juan II (CL-54).” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/s/san-juan-ii.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “USS Missouri (BB-63), anchored in Tokyo Bay, Japan, 2 September 1945, the day that Japanese surrender ceremonies were held on her deck.” Accessed 26 July 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/missouri-bb-63/SC-210649.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “USS Missouri (BB-63), anchored in Sagami Wan or Tokyo Bay, Japan, with other units of the U.S. Third Fleet, 30 August 1945.” Accessed 26 July 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/missouri-bb-63/80-G-490436.html

Naval History and Heritage Command. “Warships of the U.S. Third Fleet and the British Pacific Fleet in Sagami Wan, 28 August 1945, preparing for the formal Japanese surrender a few days later.” Accessed 26 July 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/missouri-bb-63/80-G-339360.html

“Obituaries.” Alexandria Daily Town Talk, Saturday, 26 November 1983. Page A-5. Accessed 22 July 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/?clipping_id=30042036&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjIxNjAyNDI4NiwiaWF0IjoxNTk1MzUyNDU3LCJleHAiOjE1OTU0Mzg4NTd9.50hg0Yx1WaxncuIL024uEMstzDGAdyMGa_2sO4rRPVg

O’Connor, Paul L., S.J., Bruno Bitter, S.J., and Charles A. Robinson, S.J. “Letters from Tokyo.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LXXIV, Number 4, 1 December 1945: 323-328. https://jesuitonlinelibrary.bc.edu/?a=d&d=wlet19451201-01

* Ray, Samuel H. A chaplain afloat and ashore. Salado, TX: A. Jones Press, 1962. https://library.uncw.edu/chaplains/bibliography_list.html

Ray, Samuel H. “Chaplain and Victory in the Pacific.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LXXXIX, Number 2, 1 April 1960: 108-127. https://jesuitonlinelibrary.bc.edu/?a=d&d=wlet19600401-01.2.3&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

Reynolds, Gary K, Congressional Research Service. RL30606: U.S. Prisoners of War and Civilian American Citizens Captured and Interned by Japan in World War II. The Issue of Compensation by Japan. 2002. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/us-prisoners-war-civilian-american-citizens-captured.html#count

Robinson, Charles A. “Jesuit Colleges and Universities On the Air.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, Volume 1, Number 4, March 1939: 14-19. https://jesuitonlinelibrary.bc.edu/?a=d&d=jeq19390301-01&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

Robinson, Charles A. “Radio and Education.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, Volume 1, Number 2, October 1938: 28-35. https://jesuitonlinelibrary.bc.edu/?a=d&d=jeq19381001-01&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

Rooney, Edward B. “Report of the National Executive Director.” In Jesuit Educational Quarterly, Vol. V, No. 1, June 1942: 15-25. https://archive.org/details/jesuiteducationa5119jesu/page/14/mode/2up

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1930. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/20357/rec/17

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1933. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/20495/rec/20

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1937. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/34929/rec/24

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1953. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/26903/rec/39

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1954. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/26273/rec/40

Saint Louis University. Yearbook: Archive 1955. St. Louis, MO. http://digitalcollections.slu.edu/digital/collection/historicpub/id/26069/rec/41

“Saint Patrick’s Parish Leads in Making Jesuits.” Denver Catholic Register. 17 August 1916. https://archives.archden.org/islandora/object/archden%3A2759/datastream/OBJ/view

Shaw, Henry I., Jr. The United States Marines in the Occupation of Japan. Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1969. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=0bArAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA6&lpg=PA6&dq=%22allied+prisoner+of+war+rescue+group%22&source=bl&ots=DhbVzigNlI&sig=ACfU3U2cuByUeDJLq_XZdAzOC-DbdLCSuw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiD35fLqJPqAhViKqYKHaHHAFIQ6AEwAXoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22allied%20prisoner%20of%20war%20rescue%20group%22&f=false

Sophia University. “The Battleship Missouri and Sophia University.” Sophia 100th Anniversary, No. 14. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.sophia.ac.jp/eng/aboutsophia/history/u9gsah00000007pn-att/websophia_e14.pdf

Sophia University. “The Brick-by-Brick Fund-Raising Campaign for Building Number 1.” Sophia 100th Anniversary, No. 8. Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.sophia.ac.jp/eng/aboutsophia/history/u9gsah00000007pn-att/websophiaE08.pdf

Sophia University. “History of Sophia University.” Accessed 24 July 2020. https://www.sophia.ac.jp/eng/aboutsophia/history/history/index.html

Sophia University. “In Spite of the Defeat of Japan, the Spirit of Sophia Could Prosper.” Sophia 100th Anniversary, No. 3. Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.sophia.ac.jp/eng/aboutsophia/history/u9gsah00000007pn-att/websophia_e3.pdf

Sophia University 上智大学. Sophia University: One Hundred Years 上智大学の100年. Jōchi Daigaku. 2013.

Takemae Eiji. The Allied Occupation of Japan. Trans. by Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann. New York: Continuum International Publishing, 2002.

US Army, Center of Military History. Reports of General MacArthur: MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase Volume 1 Supplement, CMH Pub 13–4. Prepared by His General Staff. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V1%20Sup/ch1.htm#b8

US Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel. The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume One 1778-1939, NAVPERS 15807. Edited by Clifford M. Drury. 1949. http://www.navybmr.com/study%20material/14281.pdf

US Navy. The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy, Volume Two 1939-1949, NAVPERS 15808. Edited by Clifford M. Drury. 1950. http://www.navybmr.com/study%20material/14282.pdf

US Navy, Bureau of Naval Personnel, Chaplains Division. United States Navy Chaplains 1946-1952: Biographical and Service-Record Sketches of 1,830 Chaplains including corrections and amendments to 1,555 sketches which appeared in United States Navy Chaplains 1778-1945, and sketches of 273 chaplains who had active duty beginning after 1 January 1946, NAVPERS-15681. Edited by Clifford M. Drury. 1953. https://books.googleusercontent.com/books/content?req=AKW5Qadlr8KaLysaEW71sGjGI6ng-HVzJZz-9I70mcnSN61w3r83HKo0SFD-FgYzJ5lYgrB-Ha7xEsZfXN1LC30_Cko0kxgSzqfzgfBMIiAo4ig-JlJP6mNkxP7ljhRqYItmFOMr5gMoHT0dgCWDXVvIp8DlmUgI-wxq6UCXTXEZtVYU8GnxGxfg5pBjEzxe383QgDTPqFJSzIzIVRvn2LHeQZP7rOCup_LJv3LGjY4Z2w2bIzhU6zOR_O_9dJt9NP14DuX7zWpRhs0oAIXjFe99aL1JwpUua-Yja5oOBUjsRjmajkfbBPE

US Navy, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Volume IV, 1969. Washington, D.C.: Naval History Division, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Navy Department, 1969. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=fpffAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA55&lpg=PA55&dq=%22allied+prisoner+of+war+rescue+group%22&source=bl&ots=NxN2JVesPu&sig=ACfU3U0Afa78C35oydK0mMigfY0MWn6shg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiD35fLqJPqAhViKqYKHaHHAFIQ6AEwA3oECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22allied%20prisoner%20of%20war%20rescue%20group%22&f=false

US Navy. United States Navy Chaplains 1778-1945: Biographical and Service-Record Sketches of 3,353 Chaplains, Including 2 Who Served in the Continental Navy. Edited by Clifford M. Drury. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1948. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=-nTGpLBa_zEC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=United+States+Navy+Chaplains+1778-1945:+Biographical+and+Service-Record+Sketches+of+3,353+Chaplains,+Including+2+Who+Served+in+the+Continental+Navy&source=bl&ots=ZDfQRw63uw&sig=ACfU3U3WSl1YhCZrSIiYTOKMeZW6vF_zWw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj0z6vCgoHqAhXm-GEKHWQtDG4Q6AEwEXoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=United%20States%20Navy%20Chaplains%201778-1945%3A%20Biographical%20and%20Service-Record%20Sketches%20of%203%2C353%20Chaplains%2C%20Including%202%20Who%20Served%20in%20the%20Continental%20Navy&f=false

US Navy, Commander Task Group Thirty Point Six. Action Report Covering Evacuation of Prisoners of War during period 29 August 1945 to 19 September 1945. 22 September 1945. http://www.mansell.com/Resources/special_files/FOLD3/Task%20Flotilla%20Six%20-%20Action%20Report,%20Evac%20of%20POWs%20from%20Tokyo%201945-08-29to09-19.pdf

US Navy, USS MISSOURI. Logbooks, July through December, 1945. https://catalog.archives.gov/search?q=%22Missouri%20(BB-63)%22%20AND%20%221945%22&f.oldScope=online&f.level=fileunit&f.allTitles=%22Missouri%20(BB-63)%22%20AND%20%221945%22&SearchType=advanced

US Navy, USS Reeves. War Diary for 13-31 August 1945. 31 August 1945. http://www.mansell.com/Resources/special_files/FOLD3/USS%20Reeves%20History%20in%203%20Parts%201945-04to09.pdf

US Navy, USS San Juan. War Diary for August 1945. 7 September 1945. http://www.mansell.com/Resources/special_files/FOLD3/USS%20San%20Juan%20-%20War%20Diary%201945-08-01to09-30.pdf

US Office of Strategic Services (OSS). “Northern Tokyo Bay OSS-Map-No.882-1942-Tokyo1-e1315844596234.” U.S. National Archives, Cartographic and Architectural Section, Record Group 226, 330/20/8. http://www.japanairraids.org/?page_id=2168

“Varia.” Woodstock Letters, Volume XLVIII, No. 1, 1919: 126-132. http://jesuitarchives.org/woodstock-letters/#woodstock048

“Varia.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LIII, 1 October 1924: 110-116. http://jesuitarchives.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/woodstock-053.pdf

“Varia.” Woodstock Letters, Volume LXXV, 1 October 1946: 269-274. http://jesuitarchives.org/wp-content/plugins/pdf-viewer-for-wordpress/web/viewer-shortcode.php?file=http://jesuitarchives.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/woodstock-075.pdf&download=true&print=true&fullscreen=true&share=true&zoom=true&open=true&logo=true&pagenav=true&find=true#locale=en-US&page=&zoom=auto

Xavier University Library. “Paul L. O’Connor portrait.” Xavier University Presidents Photographs, Exhibit: A Showcase of Scholarship, Creativity and Preservation. Accessed 22 July 2020. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/xavier_presidents/16/

Yarnell, Paul. R. NavSource Naval History: Photographic History Of The U.S. Navy. Accessed 26 July 2020. http://www.navsource.org/archives/home.html

YouTube. “Liberation of American prisoners from Urawa prison camp in Saitama, Japan towards the end of World War II.” Uploaded by CriticalPast. Accessed 22 June 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p0F-eGOFaM4&t=2m3s